Story at a Glance:

•Transplanted organs are typically sourced from “brain dead” donors. However, brain death is a surprisingly ambiguous diagnosis, and since its invention, many have argued patients who are still consciously aware are having their organs transplanted.

•Over the years, compelling evidence has accumulated suggesting this occurs, and has worsened as there has been a greater and greater need for donor organs, leading to a cruel blackmarket overseas where they are directly harvested from living donors (e.g., prisoners). Recently, government investigations showed systemic issues exist within the organ donation process that are causing inappropriate organ harvesting to occur.

•When organs are transplanted, memories, personalities, preferences, and skills (including what happened at the donors moment of death) have been repeatedly observed to transfer from the donor to recipient in a manner that strongly suggests a real transference is occurring—raising significant questions as to where our consciousness or memories comes from and who we actually are, along with the ethics of sourcing organs from non-consenting donors.

•Maintaining the viability of transplanted organs is quite challenging (e.g., making vaccination a precondition for transplants, despite evidence showing the COVID vaccine caused transplants to fail). In many cases, these challenges appear to result from aspects of consciousness being transferred from the donor to recipient.

•This article will review these points along with our preferred approaches to restoring failing organs and releasing retained emotional trauma.

When I first applied for a driver’s license, I was asked if I wanted to designate myself as an organ donor. Given my learned distrust of societal institutions (e.g., medicine) and a few concerning stories I’d come across, I opted to not be an organ donor. However, I also felt quite conflicted about doing so, particularly since I strongly believe in following the golden rule (treat others as you would want to be treated) and knew that if I needed a transplant I would be desperate for the appropriate donor to be willing to give the gift of life to me.

Since that time (when information challenging the mainstream narrative was quite difficult to find), I’ve come across much more information on the topic which paints a rather disturbing but also amazing profoundly paradigm shifting perspective on the topic (e.g., this article will detail the tangible spiritual consequences of receiving an unethically harvested organ).

However, due to my inherent conflict over this topic (e.g., many people need organs so I don’t want to discourage donations—particularly since organ shortages cause even more unethical steps to be taken to procure organs), I focused on other topics and only started this article in July. To my great surprise, a few weeks later, RFK Jr. did something I never anticipated and formally announced that there were widespread failures of the ethical safeguards in our organ donation system, after which, the Overton window was blown open and others (e.g., the head of the Independent Medical Alliance) began discussing the grim reality organs were being taken from still living people.

The Value of Organs

I have long observed that as long as enough money is on the line, there always will be a portion of people who are willing to do horrific and unimaginable things (e.g., slaughter people in overseas wars for profit). As such, I always consider the actual incentives at work when trying to appraise the reality of worrisome situations I come across.

One of the great accomplishments of the medical system was it creating the mythology it could conquer death, after which it gradually pivoted to being viewed as essential for remaining alive, and then to something which was necessary to continuously consume for “health”—all of which allowed it become incredibly profitable (and consume an ever increasing share of America’s GDP—currently totaling over 17.6% of all money spent in the United States).

Note: Medical Nemesis was an insightful 1976 book which predicted much of what followed. In Chapter 5 (pages 64–77—which can be read here), Ivan Illich highlights how the cultural conception of death evolved from an intimate, lifelong companion we had no separation from to a feared, medicalized entity to be conquered. He traced this shift through six historical stages, from the Renaissance ‘Danse Macabre’ to modern death under intensive care, where death is defined by the cessation of brain waves.

Illich argued that this medicalization, driven by the medical profession’s growing control, stripped individuals of autonomy, turned death into a commodity, and reinforced social control through compulsory care. This Western death image, exported globally, then supplanted traditional practices, contributing to societal dysfunction by alienating people from their own mortality. I agree with this, but feel the impacts of this were far more profound than even Illich hinted at.

In tandem with this, medicine began performing medical “miracles” such as being able to raise the dead (via cardiac resuscitation) and transplant organs. Opening the previously insurmountable boundaries between life and death, in turn, earned the discipline immense credit in the eyes of the public, and hence allowed it to justify being paid obscene amounts for its services (whereas in the past, doctors were paid very little and frequently only if they were able to get others better).

Note: as I will discuss in this article, crossing that boundary also called into question the materialistic (non-spiritual) paradigm modern science rests upon.

Because of this, coupled with how limited viable donor organs are, transplants rapidly became an incredibly valuable commodity (e.g., the cost of a transplant ranges from $446,800 to $1,918,700 depending on the organ—with the heart being the most expensive). As such, given how desperate many are for the organs, and how much money is at stake, it felt reasonable to assume some degree of illegal organ harvesting would occur given that people are routinely killed in other contexts for profit (e.g., in overseas wars, with a pharmaceutical company pushing lucrative drug they know can kill, or the brutal cartel violence done to establish territory).

Over the years, I then found various pieces of evidence suggesting this was happening, the worst of which I was unsure if they indeed transpired. As this is disturbing, you may want to skip the rest of this section. These included:

•Individuals being tricked into selling a kidney (e.g., in 2011, a viral story discussed a Chinese teenager who did so for an iPhone 4—approximately 0.0125% of the black market rate for a kidney, after which he became septic and his other kidney failed leaving him permanently bedridden and in 2023, a wealthy Nigerian politician being convicted for trying to trick someone into donating a kidney for a transplant at an English hospital).

•A 2009 and 2014 Newsweek investigation and a 2025 paper highlighted the extensive illegal organ trade, estimating that 5% of global organ transplants involve black market purchases (totaling $600 million to $1.7 billion annually), with kidneys comprising 75% of these due to high demand for kidney failure treatments and the possibility of surviving with one kidney (though this greatly reduces your vitality). Approximately 10-20% of kidney transplants from living donors are illegal, with British buyers paying $50,000–$60,000, while desperate impoverished donors (e.g., from refugee camps or countries like Pakistan, India, China and Africa), receive minimal payment and are abandoned when medical complications arise, despite promises of care. To quote the 2009 article:

Diflo became an outspoken advocate for reform several years ago, when he discovered that, rather than risk dying on the U.S. wait list, many of his wealthier dialysis patients had their transplants done in China. There they could purchase the kidneys of executed prisoners. In India, Lawrence Cohen, another UC Berkeley anthropologist, found that women were being forced by their husbands to sell organs to foreign buyers in order to contribute to the family’s income, or to provide for the dowry of a daughter. But while the WHO estimates that organ-trafficking networks are widespread and growing, it says that reliable data are almost impossible to come by.

Note: these reports also highlighted that these surgeries operate on the periphery of the medical system and involve complicit medical professionals who typically claim ignorance of its illegality (e.g., a good case was made a few US hospitals like Cedars Sinai were complicit in the trade).

•A 2004 court case where a South African hospital pled guilty to illegally transplanting kidneys from poorer recipients (who received $6,000–$20,000) to wealthy recipients (who paid up to $120,000).1,2

•Many reports of organ harvesting by the Chinese government against specific political prisoners.1,2,3,4,5,6 This evidence is quite compelling, particularly since until 2006, China admitted organs were sourced from death row prisoners (with data suggesting the practice has not stopped).

Note: harvesting organs from death row prisoners represents one of the most reliable ways to get healthy organs immediately at the time of death.

•Over the years, I’ve read allegations Israel illegally harvested organs from murdered Palestinians.1,2,3 I have never known what to make of these, as while some of the evidence appears compelling, neither the sources nor the evidence are definitive (often coming from those politically opposed to Israel), and logistically, collecting organs from someone who was just murdered on the battlefield before the organ expires is very difficult (and would require a specialized harvesting team to be there—something I’ve never seen reported). However, it has been officially admitted longer lasting tissues (e.g., corneas) were harvested without consent from Israelis and Palestinians bodies until the practice was banned in the 1990s.

Note: I’ve also read reports of organ harvesting occurring in Middle East conflict zones, by ISIS and in the Kosovo conflict, and with drug cartels.

Given all of this, I am unsure of the extent of “unethical” organ harvesting, but I am sure it happens (including in the most horrific manner we can imagine) and that there are likely far more cases of which have been successfully swept under the rug. Simultaneously, I strongly suspect the state sanctioned form has gradually decreased as more awareness was brought to the problem (however this may be counterbalanced by the blackmarket as the demand for organs continues to increase).

Note: many other valuable tissues (e.g., tendons and corneas) can be harvested from dead bodies. Significant controversy also exists with the ethics of how these are collected (e.g., the respect given to the bodies or how profit focused that industry is). As there is less oversight with these transplants, a significant amount of questionable conduct is rarely reported, but as the primary ethical concerns are not applicable (e.g., harvesting from a non-consenting living donor), this topic will not be discussed in this article.

Locked-In Syndrome

Since so many different parts of the brain control different facets of our being, individuals who are still conscious can sometimes completely lose control of their bodies or the ability to community with the outside world (termed Locked-in syndrome).

In one famous case, Martin, a 12-year old who fell ill with meningitis entering a vegetative state, was sent home with his parents to await his death, but instead remained alive and was brought by his father to a special care center at 5 am each day. When he turned 16, he began regaining consciousness, by 19 became fully aware of everything around him, then gradually regained some control of his eyes, and at 26 (long after he’d become a background object), a caregiver realized he was showing signs of awareness, at which point he was tested, giving a communication computer, and gradually regained his functionality (eventually getting married).

Note: two aspects I never forgot from his memoir were the years he spent being haunted by his exasperated mother (without thinking) once saying “I hope you die” and him sharing “I cannot even express to you how much I hated Barney” as the care center he spent years at, assuming he was vegetative, had him watch Barney the Dinosaur re-runs each day.

Since our ability to perceive and interact with the world depends upon many different regions of the brain, those capacities also fade as one is nearing death. However, rather than being a random process, certain functions are lost before others. In turn, it’s frequently observed within the palliative medical field (where support is offered to dying individuals) that touch and hearing are the last two senses to disappear (e.g., this study showed hearing is preserved at the end of life). As such, I often think of Martin’s story (with people who are assumed to be unaware of their environment) and periodically tell grieving families there is a possibility their “brain dead” (or soon to die) loved one can either hear their voice or feel their touch as this often provides a significant degree of closure for them (and every now and then I hear a story suggesting that final communication was perceived).

Note: a strong case can be made that modern medicine functions as the state religion of our society (with many of its rituals and behaviors having strong parallels to what was seen in other religions such as doctors’ white coats being equivalent to a priest’s robes or vaccines being its holy water you are baptized in). Cardiac resuscitation (“raising the dead”) likewise is a powerful miracle which many have argued helped cement our modern faith in medicine. What’s less recognized (as it challenges science’s spirit-denying dogma that insists consciousness resides solely within the brain) is that many resuscitated individuals have had replicable “near death experiences” where they were aware of their surroundings (often from outside their body) when their brain was “dead.” This is turn suggests that other “less recognized” senses may also persist at the time of brain death.

In parallel, while rare, every now and then cases occur when “dead” people come back to life (e.g., a Mississippi man who’d been in a body bag for a while woke up right before being embalmed—and numerous other cases exist of someone declared dead by multiple physicians later waking up1,2,3).

The Specificity of Brain Death

Sensitivity designates being able to spot something that is there while specificity designates not erroneously spotting something which wasn’t actually there (a false positive). In most cases, it is impossible to have perfect sensitivity and specificity, as once you increase one, you inevitably decrease the other (e.g., tough on crime approaches reduce crime but also inevitably result in innocent people being arrested and convicted).

This concept is typically looked at with medical diagnoses (e.g., not missing a cancer that is there but also not erroneously diagnosing a cancer and putting someone through a harmful and unnecessary cancer protocol—which for example is a common issue with routine screening mammograms), but also applies to many other fields to. In turn, I believe many issues in society boil down to finding the best possible balance between the two, but frequently, issues become polarized and irreconcilable as neither side is willing to consider the other (sensitivity or specificity) or alternately, only one side is publicly presented and we never hear about the other (e.g., we are constantly told about the dangers of not vaccinating and catching diseases but rarely if ever about the far more frequent injuries that result from vaccination).

Since organs rapidly lose their viability once someone dies, the only consistent way to ethically obtain them is from someone who has already “died” but whose body is still keeping the organs alive—in other words, from someone who is brain dead.

Given that the potential exists for individuals who are brain dead to still be alive (e.g., consider the examples I just provided) and how much money is on the line for transplants, this naturally led me to wonder if the specificity of that diagnosis might have been lowered to meet the needed quotas.

For example, The New York Times published an essay two weeks ago advocating for increasing the sensitivity for detecting brain death which many understandably found quite disturbing. To quote it:

Donor Organs Are Too Rare. We Need a New Definition of Death.

A person may serve as an organ donor only after being declared dead…Brain death is rare, though.

The need for donor organs is urgent. An estimated 15 people die in this country every day waiting for a transplant.

New technologies can help. But the best solution, we believe, is legal: We need to broaden the definition of death.

Fortunately, there is a relatively new method that can improve the efficacy of donation after circulatory death. In this procedure, which is called normothermic regional perfusion, doctors take an irreversibly comatose donor off life support long enough to determine that the heart has stopped beating permanently — but then the donor is placed on a machine that circulates oxygen-rich blood through the body to preserve organ function. Donor organs obtained through this procedure, which is used widely in Europe and increasingly in the United States, tend to be much healthier.

But by artificially circulating blood and oxygen, the procedure can reanimate a lifeless heart. Some doctors and ethicists find the procedure objectionable because, in reversing the stoppage of the heart, it seems to nullify the reason the donor was declared dead in the first place. Is the donor no longer dead, they wonder?

Proponents of the procedure reply that the resumption of the heartbeat should not be considered resuscitation; the donor still has no independent functioning, nor is there any hope of it. They say that it is not the donor but rather regions of the body that have been revived.

How to resolve this debate? The solution, we believe, is to broaden the definition of brain death to include irreversibly comatose patients on life support. Using this definition, these patients would be legally dead regardless of whether a machine restored the beating of their heart.

So long as the patient had given informed consent for organ donation, removal would proceed without delay. The ethical debate about normothermic regional perfusion would be moot. And we would have more organs available for transplantation.

Apart from increased organ availability, there is also a philosophical reason for wanting to broaden the definition of brain death. The brain functions that matter most to life are those such as consciousness, memory, intention and desire. Once those higher brain functions are irreversibly gone, is it not fair to say that a person (as opposed to a body) has ceased to exist?

In 1968, a committee of doctors and ethicists at Harvard came up with a definition of brain death — the same basic definition most states use today. In its initial report the committee noted that “there is great need for the tissues and organs of the hopelessly comatose in order to restore to health those who are still salvageable.”

This frank assessment was edited out of the final report because of a reviewer’s objection. But it is one that should guide death and organ policy today.

Diagnosing Brain Death

The diagnosis of brain death was created by a 1968 ad-hoc report (which coincided with when organ transplants had just transitioned from experimental to an accepted medical procedure. Authored by a Harvard Medical School Committee, it was titled “A Definition of Irreversible Coma” (which can be read here) and stated:

Our primary purpose is to define irreversible coma as a new criterion for death. There are two reasons why there is need for a definition:

1: Improvements in resuscitative and supportive measures have led to increased efforts to save those who are desperately injured. Sometimes these efforts have only partial success so that the result is an individual whose heart continues to beat but whose brain is irreversibly damaged. The burden is great on patients who suffer permanent loss of intellect, on their families, on the hospitals, and on those in need of hospital beds already occupied by these comatose patients.

2: Obsolete criteria for the definition of death can lead to controversy in obtaining organs for transplantation [or controversies in the courts as to if someone was brain dead].

Note: a 2018 JAMA publication indirectly admitted this question had never been answered, and instead was “solved” by a team of doctors logically arguing death should be defined as “the permanent cessation of functioning of the organism as a whole” and that since “the brain is necessary for the functioning of the organism as a whole [as] it integrates, generates, interrelates, and controls complex bodily activities,” brain death is death—despite the fact it subsequently being shown complex bodily activities (e.g., growing a baby in the womb) can occur during “brain death.”

The 1968 report in turn defined an irreversible coma as:

•No response to external stimuli.

•No movements or attempts to spontaneously breathe while on a ventilator.

•No reflexes can be solicited (including of the cranial nerves such as blinking after the eyeball is poked).

•EEG brainwaves are absent and not solicited with stimuli.

•All of the previous are replicated at least 24 hours after the initial brain death.

•All reversible causes of brain death (e.g., being on a sedative or hypothermic) being ruled out.

As there was a need for brain death, this criteria was rapidly adopted by the medical system (along with many laws that reference its medical guidelines) and has remained relatively unchanged since then, although a certain small changes have gradually been incorporated in certain jurisdictions (e.g., having two rather than one repeated examination, adopting more advanced tests to evaluate blood flow to the brain and giving children longer to recover), and most recently, in 2023, the guidelines were changed to reduce the importance of EEGs in determining brainwaves.

However, it’s important to recognize, that while it was treated as such (e.g., to justify pulling the plug or harvesting organs), this was never shown to be equivalent to death. Rather:

The authors, under the leadership of anesthesiologist Henry Beecher, stated that their primary purpose was to “define irreversible coma as a new criterion for death.”

The committee was confident that they had developed criteria for defining a state of “irreversible coma.” They were able to diagnose when a patient was never going to wake up again. It was in the subtitle that they mentioned this as a possible new definition of death. If you think about it, it’s not entirely intuitive that just because somebody is permanently unconscious, they are therefore “dead.” And I think the committee recognized this when they wrote the paper. They were confident about the irreversible unconsciousness part. They were tentative about saying that maybe this could be a new definition of death.

And this is really the root of the controversy that has persisted for the past 50 years. That link, between being irreversibly unconscious and being dead, has never really been made in a convincing way.

As such, it was immediately contested under the grounds:

•Many doctors felt it was not ethically permissible to harvest organs from someone who still had a heartbeat (and hence in their eyes was still alive), were worried ulterior motives (e.g., a need for organs) would lead to excessive diagnoses (e.g., due to the standards not being objectively applied—particularly given the inherent ambiguity of “brain death”), and were worried this practice would undermine public trust in their profession. They often also felt their had a greater duty their comatose patient (and their family) than the transplant recipient who would benefit from the death (but was not their patient).

•Many doctors felt (erroneous) EEGs sometimes falsely diagnosed a death. Likewise, individuals can have flat EEGs while still being alive and in some cases recover consciousness (e.g., there have been quite a few documented cases of people who were in comas for weeks doing this).

Note: the exact rate of recovery depends heavily on the cause of the coma (e.g., some are easily reversible, while others such as a long of blood flow to the brain are much less likely to reverse as their duration extends). I strongly suspect fMRIs would be a better way to assess this (as they have been repeatedly shown to demonstrate intentional brain activity in 20% of vegetative patients), however this modality has not been explored due to the cost and limited availability of these scans, the immense challenges of using an MRI on a ventilated patient (e.g., you need custom non-magnetic ventilators), and limited data showing EEGs have similar rates of detecting brain activity. The most recent of these evaluated 351 adults, of whom 25% were found to have no physical ability to respond to commands, but when spoken to, could activate the relevant parts of the brain to enact that command and noted that: “this phenomenon, known as cognitive motor dissociation, has not been systematically studied in a large cohort of persons with disorders of consciousness.”

•Many felt the primary motivation of the report was to avoid the cost of having to care for vegetative patients (or severely disabled ones who partially recovered) medicine was being confronted with due to improved life support technologies along with finding a sustainable source of transplantable organs.

Compelling cases have demonstrated the validity of these concerns.

In one, 21-year old Zack Dunlap suffering a severe head injury from an ATV, was comatose and put onto an unsuccessful traumatic brain injury protocol and then pronounced brain dead, after which his parents were convinced to have him be an organ donor. Shortly before the transplant helicopter arrived, the entire family, gathered to pray and say their goodbyes. As one of them was a nurse, he decided to independently evaluate Zack’s reflexes, repeatedly got responses, and while initially brushed off, Zack eventually had dramatic enough responses for the transplantation to be called off, and then fully recovered. Most importantly, Zack was fully conscious throughout this:

[After the accident], the next thing I remember was laying in the hospital bed, not being able to move, breathe, couldn’t do anything, on a ventilator, and I heard someone say, I’m sorry he’s brain-dead he’s passing away, and there’s nothing I could do you could just get mad, I couldn’t do anything to assign at all and just kind of let it go

Did you want to do anything?

I tried to what was that tried to scream tried to move, just got extremely angry yes.

So it had to be a very painful time for you?

Yes sir.

Note: due to the publicity of the case, an extensive review was conducted which concluded the gold-standard brain perfusion scan he had may have been misread (as some blinded radiologists saw blood flow to his brain while others did not) and that his slowed heart rate may have accounted for the lack of cerebral blood flow (along with propofol possibly sedating him).

In a similar case, a woman diagnosed as brain dead was in fact “locked-in” and able to hear everything around her, including a doctor telling medical students her husband was “unreasonable” for being unwilling to sign away her organs to people who could benefit from them, and that it was fine to speak this way around her as she was brain dead.

The other involved a 2013-2014 court case, where Jahi McMath a thirteen-year old California girl suffered massive blood loss, cardiac arrest and a loss of brain function (from a loss of blood flow) after a tonsillectomy (with many complications likely being due to the doctor taking hours to respond once called). After three days she was declared by dead, but rather than allow her “futile care” to be terminated, the family went to court to prevent her life support from being withdrawn, before long appealing it to a state and then district court so they could buy time to arrange their own life support. The judge then decided she was brain dead (as Standford’s chief of neurology had affirmed the diagnosis and stated she met all criteria for irreversible brain death). However, the judge compassionately granted the family’s request to briefly delay the termination of life support, and (27 days following her death) she was released to the corner and taken by the family to an undisclosed location to continue life support (later revealed to be a Catholic hospital and then an apartment).

Nine months later, the family held a press conference revealing that the daughter had regained brainwaves, that blood flow was detected to the brain, and that she moved in response to verbal commands (which were corroborated in 2017 by a UCLA pediatric neurologist). Eventually, in 2018, her life support was terminated due to internal bleeding from liver and kidney failure.

As such, cases like this demonstrated someone who was brain dead by all existing standards and deemed irrecoverable was still conscious. In turn, there are likely many more cases like this, but due to the extraordinary circumstances required to create the series of events which facilitated each of these (along with others I did not detail), it is nearly impossible to know when else this could occur.

Note: another widely publicized case was Terry Schiavo’s case, where following a heart attack, she entered a persistent vegetative state (an unresponsive coma where some functions and primitive movements of the body are still preserved). Eight years later (1998), her husband argued in court his wife would not want to live like this and succeeded in removing her feeding tube so she would starve her to death, and in 2001 it was removed. Her family disagreed (citing signs of consciousness and ulterior motives from the husband), leading to numerous appeals and national advocacy over the next four years (including President Bush signing applicable legislation), but eventually in 2005, her tube was removed and she died shortly after. As she was in a persistent vegetive state rather than “brain dead” her case, while similar, is not directly applicable to the subject at hand. However, it did bring attention to this issue and create a non-profit, which 20 years later still advocates for specific brain death cases.

When defending these practices, statements similar to this are frequently repeated:

Brain death represents a state of very severe neurological injury with no evidence, to date, that anyone correctly diagnosed will ever regain consciousness or breathe without a ventilator.

While this initially sounds compelling, if you read between the lines, it’s a unfalsifiable (meaningless) argument, as by stipulating it only applies to individuals “correctly diagnosed,” rather than disproving the criteria, all exceptions are simply “misdiagnoses.” Furthermore, in McMath’s case, it’s difficult to argue she was incorrectly diagnosed, but nonetheless, she somehow don’t count (e.g., the line I quoted stating there were no cases of erroneously diagnosed “brain death” cases came from a short JAMA paper which discussed how McNath survived years after being “brain dead”).

Note: Over the years I’ve known more intiutives and spiritual teachers than I can count who’ve worked in with hospice with soon to die patients (and occasionally comatose patients), along with speaking to people who recovered from those states (along with a few anesthesiologists who shared their exploration of what happens to one’s consciousness while under anesthesia). In many cases, they’ve shared the individual’s consciousness appears to withdraw into an inner world (unaware of what’s outside), where they are confronted with everything buried inside themselves, or they enter a transitory state where they are partly connected to their body and partly disconnected from it.

Harvesting Conscious Organs

As the years have gone by, much in the same way people occasionally wake up in the morgue, I’ve come across cases of someone waking up immediately prior to (or during) an organ harvest. For example, in one well known 2021 case, Anthony Thomas “TJ” Hoover II, a man who’d repeatedly shown signs of life (but instead was sedated) was eventually brought to the operating room to be harvested (while opening his eyes to look around as he was wheeled in). Once there, tears were observed to stream down his eyes as he mouthed “help me” and he actively thrashed around to avoid the surgery, at which point the surgeon refused to do the surgery, after which the coordinator unsuccessfully tried to get another surgeon to perform the procedure.

Note: in a similar case, a brain dead patient began breathing shortly in the operating room (leading to surgeon refusing to remove the organ) at which point the organ procurement organization (unsuccessfully) tried to get the surgeon to remove the organs.

Additional cases exist of “brain dead” organ donors recovering. For example:

-

Lewis Roberts (2021) – Declared brain stem dead; began breathing and blinking just hours before organ harvesting. Now plays sports.

-

Ryan Marlow (2022) – Diagnosis reversed after wife’s repeated insistence; recovered shortly before scheduled organ harvesting.

-

Colleen Burns (2009) – Awoke on the operating table moments before organ removal; later found by HHS to have been repeatedly misdiagnosed (along with nurses attesting to her improvement being ignored).

-

Trenton McKinley (2018) – 13-year-old boy recovered shortly before scheduled organ donation.

-

James Howard-Jones (2023) – Woke up just before life support was to be withdrawn or organs harvested, following a one-week extension requested by family.

Likewise, there are also many reports of brain dead patients not slated for harvesting having miraculous recoveries:

-

Steven Thorpe (2012) – Declared brain dead by four doctors; parents refused organ donation and he awoke two weeks later.

-

George Pickering (2015) – After feeling doctors were “moving too fast” to withdrawn his son’s life support, a (slightly intoxicated) Texas father staged an armed standoff (involving a SWAT team). Over the next three hours, George squeezed his father’s hands a few times, after which the father agreed to surrender in return for care being continued (with George then recovering).

-

Gloria Cruz (2014) – Husband refused to allow withdrawal of care; she recovered.

Additionally, a three month boy, a ten-month-old boy, a 15-year old girl, and a 65 year-old woman (all “brain dead) also had their life support turned off to facilitate a peaceful transition but instead unexpectedly survived and then recovered (in most cases fully).

Note: a recent study found over 30% of brain injured patients who were deemed unrecoverable (and hence had their life support withdrawn) would have partially or fully recovered had it not been withdrawn.

Federal Investigations

For a transplant to occur, an appropriate donor must be matched with an appropriate recipient and then have the organ transported to them when the organ is needed. All of this is facilitated by regional organ procurement organizations (56 of which exist in America), which operate under the umbrella of the organ procurement network. As there is a chronic shortage of eligible organs (leading to roughly 5,600 awaiting organs dying each year), OPTN has come under increasing scrutiny (e.g., there were scathing 2023, 2024, 2025 Congressional hearings, a 2024 Department of Justice investigation of OPTN).

Collectively, they concluded that the OPTN, due to having had a monopoly for over 40 years had become both corrupt and dysfunctional, leading to:

•Failing to modernize outdated IT and medical infrastructures, which obstructed government oversight, contributed to organ loss, resulted in a major data leak that exposed confidential patient information and prevented critical organ donation technologies from being introduced.

•Allowing critical systems to break down and relying on underqualified personnel — including organ transporters — resulting in frequent mishandling and loss of organs (e.g., 20-25% of kidneys are lost during transport).

•Never collecting an estimated 80% of eligible organs.

•Retaliating against whistleblowers who raised concerns, some of whom feared for their safety, while serious issues were routinely ignored or concealed.

•Permitting poor oversight and inadequate training — particularly in rural hospitals — which left some medical staff unable to properly determine brain death, leading to alarming allegations of live organ harvesting. In many cases, OPTN pushed surgeons to harvest these seemingly alive patients and many OPTN coordinators, based on what they’d seen, were no longer being willing to be potential organ donors.

•Misinforming or misleading families about patient status and, in some cases, seeking consent from impaired or intoxicated next of kin.

•Enabling Medicare fraud, including altering causes of death to increase transplant eligibility.

•Contributing to disparities in access, with Black, Hispanic, and disabled patients significantly less likely to receive or donate organs.

To illustrate, consider this an unusually scathing Washington Post article about the DOJ investigation:

Last year, the Senate Finance Committee explored possible conflicts of interest among the groups. It sent letters to executives of eight of them seeking information on alleged “instances in which they potentially abused their positions for monetary gain.”

The letters alleged that organ procurement organizations and their executives “have engaged in a complex web of financial relationships with tissue processors, researchers, testing laboratories, and logistics providers, which have the potential for creating conflicts of interest.”

They also said the committee had “received credible allegations” that senior members of the patient protection and policymaking committees at UNOS “may harbor undisclosed for-profit interests and may be leveraging their UNOS leadership positions to self-enrich at the expense of patient care.”

Members of Congress, in turn, were unusually concerned about all of this (e.g., they felt the horrifying reports of live organ harvesting would decrease critical donations), and as an initial step, Congress (unanimously) passed a 2023 law which gave the HHS (specifically Health Resources and Services Administration or HRSA) the authority to have control over how funding was distributed, thereby breaking up the existing monopoly (as the same federal contractor controlled both OPTN operation and their board) and motivate OPTN to improve their practices and appoint independent executives to oversee the process.

The HSRA Investigation

As RFK has not already banned every vaccine (which is not possible for him to do) he’s faced scathing condemnations from a vocal contingent within the MAHA base. In contrast, I’ve strongly supported his conduct, as beyond numerous mutual friends attesting to RFK’s conviction to make things right, I feel RFK is doing a much better job than I would have been able to do were I in his position as there are so many entrenched interests, political opponents, and resistant bureaucratic structures I felt simply proceeding at a snail’s pace was a small miracle.

Instead, RFK has found a way to proceed at a breakneck speed and again and again, I am seeing him doing things I felt were either years out or simply impossible (e.g., he recently dealt a deathblow to the mRNA platform and the billions upon billions behind it by ending the 500 million of federal mRNA vaccine contracts).

Because of the recent scrutiny surrounding the organ donation process, the HSRA (and hence the H.H.S.) opened up an extensive investigation into OPTN’s practices. This was prompted by OPTN refusing to release critical records on a recent redacted case and OPTN’s special review concluding:

Overall, there were no major concerns or patterns identified. While no major issues were found, reviewers pointed out a few small areas of improvement.

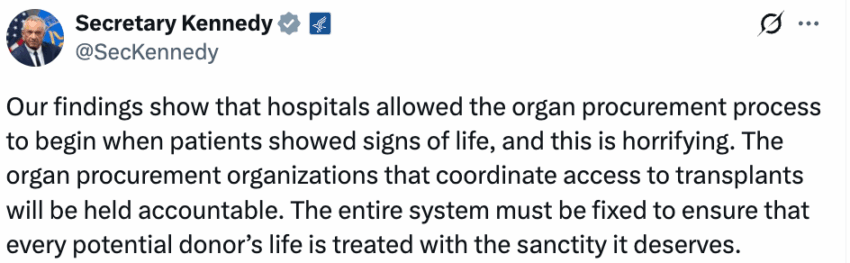

However, while the government typically lets inconvenient things like this be swept under the rug, this time an actual investigation was conducted. More remarkably, RFK Jr. (without any pressure from MAHA to do so), then made the decision to disclose those results and publicize them (e.g., in this press release and on X) despite the fact they would seriously undermine national trust in organ donations—leading to widespread condemnation for him reducing vital organ donations.

Note: in many cases, because of how difficult it is to find an appropriate balance between sensitivity and specificity, the government will use its power to suppress the issues which arise from a chosen policy (e.g., gaslighting the millions with COVID vaccine injuries so the “necessary” campaign can continue). As such, it was quite surprising RFK’s H.H.S. exposed such a critical national resource to widespread scrutiny.

To quote the (partially redacted) report:

In contrast to the OPTN report of its special review, HRSA found a concerning pattern of risk to neurologically injured patients in ███’s DSA stemming from ███ staff practices. These included:

1. Inconsistent assessment and re-assessment of patient neurologic function to detect changes that could be inconsistent with or unfavorable to DCD organ recovery. Multiple patients were documented as evincing pain or discomfort during peri-procurement events after OPO staff had either failed to adequately assess neurologic function in the setting of sedation or chemical paralysis, or had documented findings inconsistent with successful DCD recovery without change to the plan for procurement.

2. Inconsistent coordination of care with patients’ primary medical teams, including a lack of clarity in the roles of OPO staff and healthcare teams in patient care. OPO records document instances of OPO staff preempting healthcare teams’ concerns about planned care.

3. Inconsistent attention to independent decision-making authority of legal next of kin. OPO records document OPO staff approaching potential donors’ family members that they believed to be under the influence of illicit substances or lacking cognitive capacity to understand their role in the decision to donate.

4. Inconsistent collection and coding of patients’ medical data, as outlined in OPTN policies, professional best practices as well as internal policies and guidelines. A high proportion of patients for whom the OPO’s records show evidence of drug overdose or intoxication were described as having mechanisms of death other than drug-related.

HRSA’s review found 103 ANR cases (29.3%) with concerning features, including 73 patients (20.8%) for whom either the initial or subsequent neurologic status showed features not conducive to DCD procurement. At least 28 (8.0%) patients had no cardiac time of death noted, suggesting potential survival to hospital discharge.

The records HRSA reviewed suggest that patients may experience variable care from ███ depending on the hospital in which they are seen. There was a higher frequency of ANR cases relative to total DCD procurements at smaller hospitals and hospitals serving more rural populations.

Note: ANR stands for “authorized but not recovered,” indicating something unexpected went wrong at the last minute (e.g., the donor reviving) which was sufficient to stop the harvesting.

Cases submitted by ███ consistently misreported the role of illicit drug use in patient histories. Among the 351 cases reviewed by HRSA, 28 (8.0%) were reported as having drug intoxication as their mechanism of death. Review of material entered by ███ staff into their EMR shows that OPO staff had information showing that 98 (27.9%) of ANR cases showed the terminal admission and neurologic insult to be related to active use of opioids, amphetamines, or cocaine at the time of their injury. Stated another way, ███ did not document drug overdose as the mechanism of death in approximately three out of four patients with evidence of drug intoxication from the sample HRSA reviewed.

The miscoding or lack of recognition of drug intoxication is of relevance because patients in a DCD pathway may be at higher risk of their neurologic condition being masked by ongoing psychoactive effects of drug intoxication.

As opposed to brain dead donors, in which physiologic or chemical confounders of suppressed mental status must be ruled out prior to establishing a brain death diagnosis, there is no such standard for DCD evaluation.’ The risk for potential DCD patients is that depressed mental status may be ascribed to a permanent and irreversible injury, rather than slow clearance of the effects of chemical intoxication.

Twenty of the ANR cases reviewed by HRSA, including that of the index patient, involved failure to recognize high neurologic function in a victim of drug intoxication. In 15 (75%) of those cases, the OPO’s documented mechanism of death did not reflect overdose as the inciting event for the neurologic injury. As above, these numbers and rates are conservative estimates given the incomplete nature of the OPO charts.

The prevalence of these patient-level issues suggests systemic concens regarding the treatment of potential DCD donor patients by ███ staff. HRSA’s review indicates the potential for ongoing risk of harm to patients in ███ DSA, as cases similar to the 2021 index case were found to have occurred as recently as December 2024.

In short, these findings demonstrate that the alarming cases of “brain dead” patients that are actually conscious I detailed earlier in this article, are not isolated events, but rather simply the instances where, due to extraordinary circumstances around the case were able to be identified (e.g., 29.3% of the 351 ANR cases displayed signs of consciousness).

Note: the May HSRA letter also included a series of corrective measures for OPTN, and implement. There were a focus on the July, 22, 2025 hearing, where it appeared it was reported steps were being taken to do them, but nothing had yet been done and that there were numerous challenges to overcome.

Mainstream Coverage

Following the HRSA investigation, a July 2025 New York Times report corroborated many of these details:

Citing the number of Americans waiting for organs, H.H.S. said in 2020 that it would begin grading procurement organizations on how many transplants they arranged. The department has threatened to end its contracts with groups performing below average, starting next year. Many have raised their numbers by pursuing more circulatory death donors.

Note: circulatory death donors are alive (with some brain activity) but have been deemed unable to survive. To “ethically” harvest their organs, life support is withdrawn, with the harvest beginning immediately once the heart stops beating. As there is far more subjectivity to this diagnosis, there have been numerous cases of harvests being attempted on someone still alive (e.g., many were covered throughout the NYT article such as a 42-year old who was supposed to be dead but surgeons discovered still had a beating heart and was breathing after they opened her).

Employees said some organizations had blown past safeguards, potentially rushing the process. For instance, coordinators are not supposed to approach a patient’s relatives until the family has decided to withdraw life support, but workers said that rule was frequently violated.

The Times found that some organ procurement organizations — the nonprofits in each state that have federal contracts to coordinate transplants — are aggressively pursuing circulatory death donors and pushing families and doctors toward surgery. Hospitals are responsible for patients up to the moment of death, but some are allowing procurement organizations to influence treatment decisions.

“All they care about is getting organs,” said Neva Williams, a veteran intensive care nurse at the hospital. “They’re so aggressive. It’s sickening.”

Fifty-five medical workers in 19 states told The Times they had witnessed at least one disturbing case of donation after circulatory death…[and] coordinators persuading hospital clinicians to administer morphine, propofol and other drugs to hasten the death of potential donors.

Bryany Duff, a surgical technician in Colorado, said one patient, a middle-aged woman, was crying and looking around. But doctors sedated her and removed her from a ventilator, according to Ms. Duff and a former colleague. The patient did not die in time to donate organs but did so hours later. “I felt like if she had been given more time on the ventilator, she could have pulled through,” Ms. Duff said. “I felt like I was part of killing someone.”

Afterward, Ms. Duff quit her job and temporarily left the field. “It really messed with me for a long time,” she said. “It still does.”

In Miami in 2023, a potential donor who had broken his neck began crying and biting on his breathing tube, which a procurement organization worker said he interpreted as him not wanting to die. But clinicians sedated the patient, withdrew life support, waited for death and removed the organs, according to the worker and a colleague he told at the time.

In West Virginia, doctors were taken aback after Benjamin Parsons, a 27-year-old man paralyzed in a car accident, was brought to an operating room and asked to consent to donating his organs as he was coming off sedatives. Communicating through blinks, he indicated that he did not give permission. Still, coordinators initially wanted to move forward, according to text messages and interviews.

In New Mexico, a woman was subjected to days of preparation for donation, even after her family said that she seemed to be regaining consciousness, which she eventually did. In Florida, a man cried and bit on his breathing tube but was still withdrawn from life support.

In 2022, when she was 38 and homeless, Ms. Gallegos was hospitalized and went into a coma. Doctors at Presbyterian Hospital in Albuquerque told her family she would never recover. Her relatives agreed to donation, but as preparations began, they saw tears in her eyes. Their concerns were dismissed, according to interviews with the family and eight hospital workers. Donation coordinators said the tears were a reflex.

On the day of the planned donation, Ms. Gallegos was taken to a pre-surgery room, where her two sisters held her hands. A doctor arrived to withdraw life support. Then a sister announced she had seen Ms. Gallegos move. The doctor asked her to blink her eyes, and she complied. The room erupted in gasps.

Still, hospital workers said, the procurement organization wanted to move forward. A coordinator said it was just reflexes and suggested morphine to reduce movements. The hospital refused. Instead, workers brought her back to her room, and she made a full recovery.

After relatives agree, it can take several days to prepare for organ retrieval. During this time, the hospital is supposed to keep treating the patient, including looking for signs of recovery.

In reality, said 16 workers at hospitals in a dozen states, once patients are approved for donation, hospitals sometimes put them in the care of young residents or fellows who tend to defer to procurement organizations.

Dr. Alejandro Rabinstein, chair of hospital neurology at the Mayo Clinic, said medical workers sometimes lacked the experience to tell whether a patient’s movements were a sign of recovery or meaningless reflexes. “Training can be a real issue, especially in smaller hospitals,” he said.

“I think these types of problems are happening much more than we know,” said Dr. Wade Smith, a longtime neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco, who frequently evaluates potential donors and has studied donation after circulatory death.

Living With a Transplant

While transplants are a “medical miracle” they are far from perfect and because of this, there is always a risk the organ will fail. For example, the failure rate for common transplants are as follows:

•Lung: 10.4% (within a year), 72% (within 10 years)

•Heart: 7.8% (within a year), 46% (within 10 years)

•Kidney: 5% (within a year), 46.4% (within 10 years)

•Liver: 7.6% (within a year), 32.5% (within 10 years)

Note: the 10 year survival rates for lung and heart grafts referenced patient survival rather than graft survival (whereas graft survival alone would likely be lower).

Given the cost, danger and limited availability of transplants this is quite concerning. For this reason, organs are prioritized for those with the highest likelihood of the organ not failing, much of which relates to the likelihood patients are dutifully follow a rigid regimen to reduce their likelihood of a rejection, which typically includes:

•Taking care of their general health (e.g., diet and exercise)

•Permanently abstaining from cigarette, drug and alcohol use.

•Complying with existing treatment regimens for their other chronic health conditions (e.g., high blood pressure).

•Complying with a lifelong regimen of immune suppressing transplant medications.

•Undergoing routine bloodwork to detect signs an organ is beginning to fail and greater immune suppression in needed.

•Doing everything they can to reduce their risk of infections (as they are on immune suppressing drugs) and aggressively treating those they come down with (as infections can cause transplanted organs to fail).

Many issues can arise with each of these. For example, the immune-suppressing medications used to prevent organ rejections normally cost at least 10,000-30,000 a year (or sometimes even more). Likewise, they have a variety of side effects such as from mild tremors, headaches and GI upset at low doses to serious infections, kidney damage, and metabolic disturbances at high doses. Lastly corticosteroids (which are used for certain aspects of transplant management such as initially and in rejection episodes) and have a more extensive set of side effects (detailed here).

Note: DMSO has been shown to prevent the rejection of certain grafts (e.g., skin grafts and insulin producing cells), and likely would help with transplanted organs (but this has not yet been tested).

Likewise, comprehensive vaccination is typically required prior to transplantation as beyond them theoretically reducing the risk of dangerous infections in these immune suppressed patients, vaccines are thought to be much less effective once a patient is on immune suppressing drugs.

Many then became aware of this during COVID-19 as there were numerous highly publicized cases of someone either not getting a necessary transplant because they refused the COVID-19 vaccine or someone doing so to get on the waitlist and then succumbing from the effects of the vaccine. This created significant public outrage, as many felt necessary medical care was again being withheld for ideological reasons (with doctors justifying this position by resolutely insisting the (COVID vaccine was “safe and effective” regardless of the evidence to the contrary).

In my eyes, the most frustrating part of this was that I rarely, if ever, heard it mentioned that the COVID vaccine could actually increase one’s risk of a transplant rejection (e.g., due to it obstructing blood circulation or it provoking autoimmunity). Initially, I became aware of this issue after a patient with a bone marrow stem cell transplant shared that people in his support group had had their transplants fail (which I suspected was linked to the mRNA vaccines concentrating in the bone marrow)—yet no one in the medical field was made aware of this critical issue.

Following this I came across a paper (I’m still surprised was published) comprising 44 cases of corneal graft rejections following COVID vaccines (along with a separate paper detailing one that had been there for 25 years but failed 13 days after Pfizer). I then learned of similar results with kidney transplants (36 reported cases, including one who had worsening renal function and proteinuria 21 days after their Pfizer vaccine), liver rejections (12 cases) and a few reports of it happening with other organs (e.g., the heart, lung, and pancreas), while in parallel, I heard of a few (non-published) cases within my network where this happened.

Note: another retrospective study found 1.8% of those who received a COVID vaccine had their corneal grafts fail, while 1.6% of those who had flu shots had their grafts fail.

Furthermore, beyond the overt medical issues transplant patients face, there are also a variety of significant psychiatric ones they must contend with.

The Heart’s Code

One of the least recognized aspects of organ donations is an odd observation with them, which like near experiences, challenges our fundamental conception of what consciousness actually is—in many cases, the personality, preferences and memory of a donor will transfer to the recipient (particularly with heart transplants).

For example, Dr. Benjamin Bunzel in the Department of Surgery at the University Hospital in Vienna studied 47 heart transplant patients and found that 79% believed their personality had not been affected by the transplant (but gave signs indicating otherwise to the interviewer), 15% believed it had changed due to the life-threatening event of transplantation rather than from their new heart, while 6% (three in total) reported a distinct change of personality due to their new hearts. In those three individuals, each noted that they felt compelled to change their prior feelings and reactions to accommodate what they sensed as coming from the memories of their donor.

One reported switching from always being anxious to having a calm heart. The second (a 45-year-old man who received the heart of a 17-year-old boy) reported that he became driven to listen to loud music with headphones or from his car stereo, while his family reported that it seemed as though the little boy in him had come out. The final individual reported being drawn to attending church, his marriage changing and feeling as though his donor was living inside him.

Note: when studied, approximately 10% heart transplant recipients reported becoming overtly sensitive to experiencing emotions they believed come from their donor.

The most well-known personality change was detailed within A Change of Heart, a memoir written by Clair Sylvia, who at the age of 47, received a heart and lung transplant.

[At the time her transplant] she heard from a nurse that her donor was an 18-year-old boy from Maine who died in a motorcycle accident, but the hospital refused to tell her more, arguing (as most hospitals do) that this is an emotional can of worms for all concerned.

Five months afterwards she had a vivid dream about a tall, thin young man whose name was Tim, and whose surname began with L. In the dream, writes Sylvia, “we kiss, and as we do I inhale him into me. It feels like the deepest breath I have ever taken. And I know at that moment the two of us, Tim and I, will be together for ever. I woke up knowing – really knowing – that Tim L was my donor and that some parts of his spirit and personality were now in me.”

At first, Sylvia accepted the advice to leave well alone, but she continued to experience disturbing, unfamiliar feelings and appetites – from her strange new desire to drink beer [which started immediately after the surgery] and eat chicken nuggets, to the profound sense that “the very centre of my being was not mine”.

The mysterious new entity within her body reminded her of pregnancy, when she felt she embodied something “foreign and beyond my control, yet terribly precious and vulnerable [as if] a second soul were sharing my body”. And that soul was stereotypically masculine, making her more aggressive and confident. Friends remarked that after the transplant she was walking more like a man and she found herself attracted by rounded, blonde women – “as if some male energy in me was responding to them.”

It was not until 1990, she says, that Sylvia traced the identity of her donor through his obituary in a local paper. His name was Tim, his surname did begin with L, and when Sylvia eventually visited his family she learnt that he had been restlessly energetic, with a love of chicken nuggets, junk food and beer [the habits she adopted after the transplant].

Note: another woman who received the heart of a young man reported “When we dance now, my husband says I always try to lead. I think it’s the macho male heart in me making me do that.”

Pearsall’s Discoveries

In certain cancers, treating them requires taking a heavy dose of chemotherapy that destroys the bone marrow (marrow produces your blood cells and immune system). In these patients, they often first receive chemotherapy and then a bone marrow transplant from a healthy donor to replace their lost bone marrow. Since Paul Pearsall went through this and was a neuropsychologist, he became compelled to study the psychological effects of transplantation and become a counsellor for individuals who experienced “significant and inexplicable changes in personality” after transplants.

In writing The Heart’s Code Pearsall compiled interviews from 73 heart transplant recipients (along with their family members), 67 individuals who received other organ transplants, and interviewed the family members of 18 now deceased organ donors. To quote Pearsall:

When I listen to the tapes of my interviews with heart and heart-lung transplant recipients and the donor families, I am still taken aback by what they’ve shared with me.

From these interviews he found numerous common patterns such as:

•Repeatedly recalling the traumatic manner in which the donor died either through dreams or by feeling something resembling the fatal injury the donor experienced in their own body.

Note: in many cases, transplant recipients are told very little about the donor (as this is believed to be more psychologically healthy for both the recipient and the donor’s family), making the accuracy of these recollections quite compelling.

•Changes in culinary and music preferences that matched those of the donor. For example, lifelong vegetarians became carnivores, and carnivores became vegetarian.

•Changes in sexual preferences matching those of the donor (e.g., a lifelong lesbian becoming attracted to men and then marrying one, another woman receiving the heart of a sex worker and then becoming hypersexual, or another instead losing their sex drive).

Note: one of my colleagues has a male patient who received a female heart, then became compelled to become a woman and is now undergoing a gender transition (something the patient had had never even thought of prior to the transplant). Pearsall also shared that a change in gender orientation be reported to him by one transplant recipient he interviewed. All of these examples shed an interesting light on the belief that “love is in the heart.”

•Sudden overpowering emotions coming over them out of nowhere they feel as though they have no control over (my mentor also observed this). Likewise, this was also observed by a Yale surgeon who documented the experiences of a heart transplant recipient the surgeon followed throughout their hospitalization:

I can be sitting here feeling fine and all of a sudden something clicks and I get nervous and everything starts going. Something in my body changes, as if somebody pushed a button. I talked to another transplant patient—he’s in his fifth year—and he says it still happens to him.”

Heart Transplant Experiences

In his book, Pearsall shared some of the most compelling cases he came across. Given his meticulous use of citations, that he cowrote a paper detailing many inexplicable personality transferences with an academic who independently verified those stories, that he was regularly invited to speak on national television, and the fact that many of his stories match the patterns my colleagues have come across, I am inclined to believe Pearsall was being truthful. Nonetheless, some of these stories are so extraordinary, I am nonetheless a bit skeptical of them, and unfortunately Pearsall is no longer alive, so it’s no longer possible to directly discuss them with him.

Those stories are as follows:

I recently spoke to an international group of psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers meeting in Houston, Texas. I spoke to them about my ideas about the central role of the heart in our psychological and spiritual life, and following my presentation, a psychiatrist came to the microphone during the question and answer session to ask me about one of her patients whose experience seemed to substantiate my ideas about cellular memories and a thinking heart.

The case disturbed her so much that she struggled to speak through her tears. Sobbing to the point that the audience and I had difficulty understanding her, she said, “I have a patient, an eight-year-old little girl who received the heart of a murdered ten-year-old girl. Her mother brought her to me when she started screaming at night about her dreams of the man who had murdered her donor. She said her daughter knew who it was. After several sessions, I just could not deny the reality of what this child was telling me.

Her mother and I finally decided to call the police and, using the descriptions from the little girl, they found the murderer. He was easily convicted with evidence my patient provided. The time, the weapon, the place, the clothes he wore, what the little girl he killed had said to him . . . everything the little heart transplant recipient reported was completely accurate.” As the therapist returned to her seat, the audience of scientifically trained and clinically experienced professionals sat in silence.

As far as I know, no one has been able independently confirm the above story happened, as each existing reference to it cites Pearsall’s book. However, there are also other cases of the donor’s final memories being recalled by the recipient.

For example, a 36 year-old female received the heart of a 21 year-old girl who was killed while running across the street to show her fiancé a picture of her new wedding dress. That recipient reported having a dream almost every night about the girl stating:

I know she was young and pretty and very happy. I’ve always been sort of a somewhat down type of person yet, somehow [since the transplant], I have this new happiness in me I never experienced before

Note: a profound improvement in her mood was also immediately noticed by her family.

There are other compelling examples as well:

I met the family of my donor and they said their son was a bright young [twenty three year-old] artist and that he was gay. Now I wonder if, when I look at my husband, I am looking at him like a woman would look at him like I used to do, or if I am looking at him like a young gay man would look at him. And one more thing. His mother said they shot him in the back. After my surgery, I’ve had shooting pains in my lower back, but I guess that’s just the surgery acting up.

Husband of recipient: She has completely changed how she dresses now [she wears much more revealing clothes now] and sometimes during the night she will awake suddenly and scream. I used to think she was having a heart attack, but she would point to her back and say it was like a shooting pain right in the middle of her back.

The next story comes from a 41 year-old male who received the heart of a 19 year-old girl who was killed when her car was struck by a train:

I felt it when I woke up. You know how it feels different after a thunderstorm or heavy rain? You know that feeling in the air? That’s kind of how it felt. It was like a storm had happened inside me or like I had been struck by lightening. There is a new energy in me. I feel like nineteen again. I’m sure I got a strong young man’s heart because sometimes I can feel like a roar or surging power within me that I never felt before. I think he was probably a truck driver or something like that, and he was probably killed by a cement truck or something like that. I feel this sense of speed and raw power in me.”

Wife of recipient: “He’s a kid again. He used to struggle to breathe and had no stamina at all, but now he’s like a teenager. The transplant changed him completely. He keeps talking about power and energy all the time. He says he has had several dreams that he is driving a huge truck or is the engineer of a large steam engine. He is sure that his donor was driving a big truck that hit a bigger truck.”

Sometimes the transfer of memories is not as apparent without the full context to interpret it:

Oh my God, David, no!,” cried Glenda when she saw the bright lights headed straight for their car. As the squeal of the tires burning to grip the road became one with her own shrill shriek of helpless terror, she knew that she had lost her husband forever. Moments before the car came crashing through their windshield, the couple had argued over something silly and had been sitting in resentful silence. They had had these little emotional scuffles before, but unlike in the past when they had had skirmishes, this time there would be no opportunity to apologize and reconfirm their love.

Glenda is a practicing family physician. She is well-versed in bioscience and, as I do, admires the rigor and healthy skepticism of modern science. Now, however, the power of something that transcends what science calls common sense was tugging at her heart. “David’s heart is here,” she added. “I can’t believe I’m saying that to you, but I feel it. His recipient is here in this hospital.” At that moment, the door opened and the young man and his mother walked hurriedly down the center aisle of the chapel.

Glenda’s hand began to tremble and tears rolled down her cheek. She closed her eyes and whispered, “I love you David. Everything is copacetic.” She removed her hand, hugged the young man to her chest, and all of us wiped tears from our eyes. Glenda and the young man sat down and, silhouetted against the background of the stained-glass window of the chapel, held hands in silence.

Speaking in her heavy Spanish accent, the young man’s mother told me, “My son uses that word ‘copacetic’ all the time now. He never used it before he got his new heart, but after his surgery, it was the first thing, he said to me when he could talk. I didn’t know what it means. He said everything was copacetic. It is not a word I know in Spanish.” Glenda overheard us, her eyes widened, she turned toward us and said, “That word was our signal that everything was OK. Every time we argued and made up, we would both say that everything was copacetic.

Another case illustrates the different ways a donor’s heart can diffuse into the consciousness of the recipient:

It’s really strange, but when I’m cleaning house or just sitting around reading, all of a sudden this unusual taste comes to my mouth. It’s very hard to describe, but it’s very distinctive. I can taste something and all of a sudden I start thinking about my donor, who he or she is, and how they lived. After a while, the taste goes away and so do the thoughts, but the taste always seems to come first.

One case argued strongly against preconceived notions of the recipient causing the personality changes:

A 47 year-old white male foundry worker, who received the heart of a 17 year-old black male student, discovered after the operation that he had developed a fascination for classical music. He reasoned that since his donor would have preferred ‘rap’ music, his newfound love for classical music could not possibly have anything to do with his new heart. As it turned out, the donor actually loved classical music, and died “hugging his violin case” on the way to his violin class [he was hit by a car].

One case illustrates many of the different changes that can occur simultaneously:

The donor’s mother: “My Sara was the most loving girl. She owned and operated her own health food restaurant and scolded me constantly about not being a vegetarian. She was a great kid — wild, but great. She was into the free-love thing and had a different man in her life every few months. She was man-crazy when she was a little girl and it never stopped. She was able to write some notes to me when she was dying. She was so out of it, but she kept saying how she could feel the impact of the car hitting them. She said she could feel it going through her body.”

The recipient: “You can tell people about this if you want to, but it will make you sound crazy. When I got my new heart, two things happened to me. First, almost every night, and still sometimes now, I actually feel the accident my donor had. I can feel the impact in my chest. It slams into me, but my doctor said everything looks fine. Also, I hate meat now. I can’t stand it. I was McDonald’s biggest money-maker, and now meat makes me throw up. Actually, whenever I smell it, my heart starts to race. But that’s not the big deal. My doctor said that’s just due to my medicines. I couldn’t tell him, but what really bothers me is that I’m engaged to be married now. He’s a great guy and we love each other. The [chemistry] is terrific. The problem is, I’m gay. At least, I thought I was. After my transplant, I’m not…I have absolutely no desire to be with a woman. I think I got a gender transplant.

Note: Susie’s brother also noted that Susie had been an outspoken lesbian but following the transplant, that personality completely disappeared.

One of the most interesting cases was first documented in the Daily Mail. It suggests that abstract skills can also be transferred:

William Sheridan’s drawing skills were stuck at nursery level. His stick figures were the sort you would expect of a child.

But as he convalesced after a heart transplant operation, he experienced an astonishing revelation.

Suddenly he was blessed with an artistic talent he simply did not recognise, producing beautiful drawings of wildlife and landscapes.

He was even more amazed when he discovered what he now believes to be the explanation. The man who donated his new heart was a keen artist.

Note: Pearsall also shared the case of a sensitive nurse who worked in a cancer unit. Two years after her transplant, she became an energy healer and remarked that “I had a new heart with new energy and memories physically placed in me. That really gets your brain’s attention about ‘otherness’ and ‘individuality’.”

In rare cases, heart transplant recipients are able to meet their donors, due to a phenomenon known as “domino transplants” where a patient with failing lungs receives both a heart and lungs simultaneously and then donates their heart to someone else. When Pearsall interviewed a heart transplant recipient (Fred) and his donor (Jim), both of their wives noted the husband had taken on personality traits of their heart donor (e.g., the depression and romanticism of Jim’s now deceased donor), and that Fred periodically subconsciously mistook his wife for Jim’s wife.

A longer list of some of the most compelling cases Pearsall came across can be found in the article he published. Many of the themes mentioned above are echoed within the article’s stories (e.g., the donor communicating to their family through the recipient, and the donor’s talents, fears or memories being transferred to the recipient). Additionally, a brief documentary compiled on Pearsall’s work shows live testimonials of transplant recipients affirming these inexplicable transferences of consciousness do in fact happen.

Note: Numerous readers have also shared with me that while they had not had a transplant, they had received significant blood transfusions (e.g., to save them from otherwise fatal traumatic blood loss) and had noticed they had experienced some of the personality changes described throughout this article, although not to the same degree as those seen in Pearsall’s cases. This could argue that part of your personality is information within the blood—something congruent with ideas put forward by long forgotten Russian research on the full capacities of the heart.

Other Transplanted Organs

Pearsall has also observed personality changes with other organ transplants (e.g., liver and kidney) such as recipients sensing changes in their sense of smell, food preferences, and various emotional factors. However, unlike the heart transplants, these changes were less dramatic, usually transitory and could potentially be due to something else (e.g., transplant medications).

My colleagues who have worked with transplant recipients have seen similar changes to those described by Pearsall in kidney, liver, and lung transplants, and also noted that certain challenging emotions will spontaneously emerge in the transplant recipients. However, like Pearsall, they believe the most dramatic changes occur in heart transplant recipients.

Within Chinese Medicine (and to varying extents other holistic medical systems), a belief exists that many of the emotions within the body are generated by the internal organs (while other deeper ones like compassion are generated directly by the spirit). In turn, an imbalance in the organ will generate the emotion (which resolves once the organ is treated), and conversely, excessive amounts of the paired emotion will cause physiologic dysfunction in the organ.

The five classic Chinese pairings are the liver with anger, the lung with grief, the heart with joy (which becomes problematic when excessive), the spleen with pensiveness (the emotion that drives excessive thought), and the kidneys with fear. For instance, excessively drinking alcohol (which injures the liver) is known to create both anger and depression (another emotion of the liver) in the alcoholic.

Note: in Chinese medicine, a total of 12 different organs have emotions associated with them.