Many years ago, I was watching a nature show. It was about some hunter-gatherers on some Pacific island. The film crew went right up and talked to one of the hunter-gatherers about his life — hunting, gathering, finding and killing witches among his fellow tribesmen, and so on. But as they talked, I realized that there must be a giant video camera right in the face of this tribesman. And he wasn’t even reacting to it. What was this strange, unnaturally shaped object, made of strange unknown materials, and potentially possessing magical powers? Didn’t he wonder? And didn’t he ask himself if he could get something like it, and use it for whatever these strange foreigners were using it to do?

I often think about the example of the tribesman and the video camera. It’s a small version of a story that happens again and again, on a far grander scale, determining the fate of entire nations and geopolitical systems of power: absorption of foreign technology. Most of the things you use on a day-to-day basis were not invented in the country in which you live (even if you live in America). They were invented all over the world, and one crucial reason you have access to them is that your society deemed it fitting to allow those technologies into the country.

Adopting foreign technologies sounds like a no-brainer, but there are lots of risks involved. Hierarchies of power and status can be disrupted, creating political chaos. Existing economic relationships can shift, creating unexpected winners and losers. But perhaps most frighteningly, foreign technology can change a country’s traditional culture.

One Pacific island civilization that was determined to absorb foreign technology without letting it change their culture was Japan. When the “black ships” from the West arrived in the 1850s and demonstrated how helpless Japan was in the face of foreign powers, the country’s leadership (after a brief civil war) decided that their only choice was to absorb foreign technologies and institutions. But they wanted to preserve Japan’s traditional culture as well. They thus came up with the concept of “wakon yosai” (和魂洋才), which translates roughly as “Japanese soul, Western technology”. Over the course of the next century and a half, Japan intentionally strove to preserve elements of its unique culture even as it reshaped its society around new gadgets and production processes.

Travel to Japan today, and I guarantee that unless you are staying in a very backwoods rural place, the room where you stay will have an air conditioner. It will almost always be a “mini split”, or wall unit, looking much like the image at the top of this post. It will be quiet, but powerful enough to keep your room cool even in the increasingly hot summers that Japan now suffers due to climate change. This is a technology never available in Japan’s premodern days, and yet it has been near-universally embraced with no apparent degradation to the country’s traditional culture or national pride.

Europe is different. Data sources differ, but nobody puts AC usage in Europe (or the UK) at more than around 20%. This technology, which almost all Japanese people enjoy, is one that most Europeans do without.

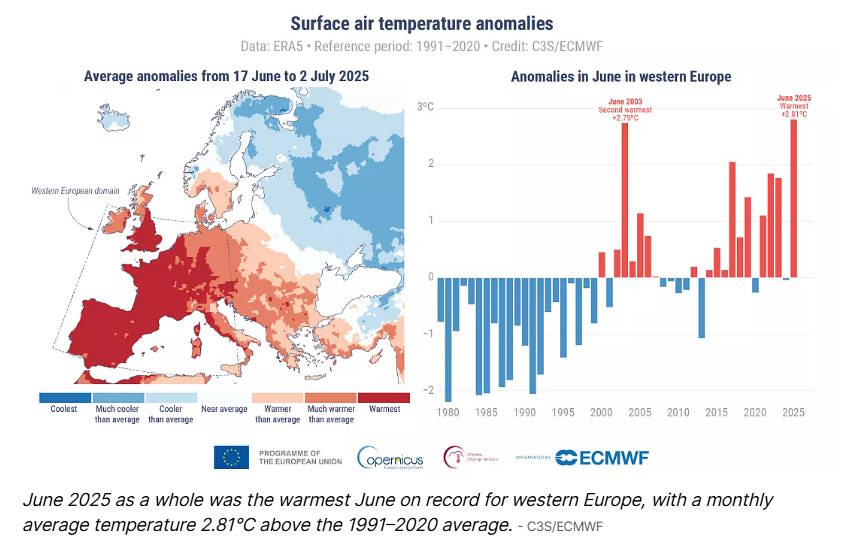

You might think Europe is simply too far north to need AC. But latitude is no longer the defense against heat that it used to be, because climate change is stalking the region:

With this rise in temperature — and the aging of the European population — has come a rise in preventable death. Estimates of heat-related mortality vary, but the most commonly cited number is 175,000 annually across the entire region. Given that Europe has a population of about 745 million, this is a death rate of about 23.5 per 100,000 people per year. For comparison, the U.S. death rate from firearms is about 13.7 per 100,000.

So the death rate from heat in Europe is almost twice the death rate from guns in America. If you think guns are an emergency in the U.S., you should think that heat in Europe is an even bigger emergency.

Most of this death is preventable. The technology that prevents it is air conditioning. Barreca et al. (2016) find that heat deaths in America declined by about 75% after 1960, and that “the diffusion of residential air conditioning explains essentially the entire decline in hot day–related fatalities”. Essentially, wherever AC gets rolled out, heat-related death plunges. Taking Barreca’s estimate and applying it to Europe suggests that as many as 100,000 European lives — 0.013% of the population — could be saved every year if the 80% of European households who don’t have AC were to get it.1

And yet Europe has not done this. The official reason — at least, where one is given — is that AC uses electricity, which contributes to climate change. For example, this is from a 2022 article in MIT Technology Review:

Climate change is making extreme heat the norm across more of the world, increasing the need for adaptation. But in the case of AC, some experts are concerned about how to balance that need with the harms the solutions can cause…

[M]any Europeans are hesitant to welcome air conditioners with open arms. “Seeing AC as a solution to heat waves and to climate change is of course a bit problematic because of the energy that’s being used,” says Daniel Osberghaus, an energy and climate economics researcher at the Leibniz Centre for European Economic Research in Germany.

Today, cooling devices like ACs account for about 10% of global electricity consumption—and since most of the world’s electricity still comes from fossil fuels, that’s a significant chunk of worldwide emissions. Because of their massive energy use, “they do get a bad reputation,” says Kevin Lane, an energy analyst at the IEA.

Many other stories also mention climate as a reason Europe resists AC. Green organizations like the World Resources Institute, which have a lot of influence in Europe, consistently recommend far less effective “passive cooling solutions” due to emissions concerns. And European regulations do block AC, by mandating that newly built buildings be carbon-neutral. (This in addition, of course, to good old NIMBYism also blocks AC installation, especially in the UK.) Tyler Cowen writes:

European governments do a great deal to discourage air-conditioning, whether central AC or window units. You might need a hard-to-get permit to install an AC unit, and in Geneva you have to show a medical need for it. Or in many regions of Europe, the air conditioner might violate heritage preservation laws, or be illegal altogether. In Portofino, Italy, neighbors have been known to turn each other in for having illegal air-conditioning units. The fines can range up to €43,000, though most cases are settled out of court by a removal of the unit.

In fact, Andrew Hammel alleges that Germany has raised climate-based opposition to AC to the level of an ideological crusade. Here are some excerpts from his thread:

I believe attitudes toward air-conditioning are class markers in many European countries. Air-conditioning is seen as prototypically American, and that’s important…

The urban haute bourgeoisie — bureaucrats, public media executives, NGO employees, humanities grads, journalists, professors, lawyers, judges, etc. — are the holdouts [in terms of installing AC]…

First of all, *every one* of these people has a story about visiting the USA and nearly freezing to death in an over air-conditioned store or office. Every. Damn. One…To these people, A/C is the ultimate American solution to a problem. Instead of accepting nature as it is, Americans use expensive, wasteful technology to artificially change the environment to fit their fat, lazy lifestyles. They insist on defying and conquering nature, not “cooperating” with her. And they don’t care if they cook the planet while they do so…

[T]he European urban haute bourgeoisie turns it into a rigid ideological aversion to any form of air-conditioning…These people regard these decisions not just as their personal lifestyle choices, but rather as a *model for all of society*. They regard themselves as a revolutionary vanguard of advanced ecological consciousness which must aid the less enlightened to reduce their carbon footprints. And these people *run German society*…Urban planners and people who create construction codes in Germany are also brigadiers in the anti-A/C jihad…

Which is why it’s pretty common on sweltering days to hear Germans complain about the “goddamn ‘eco-this’ ‘organic-that’ pencil pushers” who continue to force them to sweat for hours in overheated hospitals, classrooms, and offices.

This is immediately recognizable as the poisonous ideology of degrowth. Degrowth frames climate change as a problem of personal overconsumption and extravagance to be curbed by austere self-restraint and government policy, rather than as a technological problem to be overcome by installing green energy. This is foolish, of course — it leads to human suffering while not doing much to actually curb climate change. But it’s very popular in northern Europe.

The climate-based crusade against AC is a little infuriating, because it probably kills a lot more people than the reduced emissions save. Right now, Europe is responsible for only about 13% of global carbon emissions from fossil fuel use, meaning that the climate impact of installing AC all over the region is pretty minimal. Does anyone think that incredibly tiny margin of emissions reduction is really worth tens of thousands of lives a year?

But from reading anecdotes like Hammel’s, I kind of suspect that there’s a second, deeper reason why Europe so far refuses to install AC: protection of traditional culture. The thing about German elites pooh-poohing AC as an unnecessary American extravagance suggests that some Europeans view lack of AC as quintessentially European culture — a tradition by which Europeans can define their own uniqueness vis-a-vis the rest of the world.

Many articles about Europe’s strange reluctance to use AC hint at this attitude. For example, here’s CNN:

A big part of the reason [they don’t install AC] is many European countries historically had little need for cooling, especially in the north…“In Europe… we simply don’t have the tradition of air conditioning… because up to relatively recently, it hasn’t been a major need,” said Brian Motherway, head of the Office of Energy Efficiency and Inclusive Transitions at the International Energy Agency. [emphasis mine]

And here’s Euronews:

The rest of this story lies in history and culture…Southern Europe built its cities to cope with heat: thick walls, shaded windows, and street layouts designed to maximise airflow…That’s also why white paint dominates the picturesque skylines of Mediterranean places like Santorini in Greece or Vieste in Italy: The bright surfaces reflect sunlight and radiant heat, helping interiors stay cooler…In northern Europe, on the other hand, summers were once mild enough that cooling was rarely needed…Air conditioning, when it appeared in Europe, was seen as a luxury or even a health risk. Many Europeans still believe exposure to cold air can make you sick, and the stereotype persists that AC is for rich people.

And the WSJ reports that there are widespread superstitions about the dangers of this technology that most of the rest of the world uses every day:

In France, media outlets often warn that cooling a room to more than 15 degrees Fahrenheit below the outside temperature can cause something called “thermal shock,” resulting in nausea, loss of consciousness and even respiratory arrest. That would be news to Americans[.]

Even if climate is the official, intellectual reason for Europe refusing live-saving AC, the idea that AC goes against Europe’s traditional culture is probably an important underlying motivator.

(This trend isn’t unique to Europe, of course. Americans may pride themselves on being more futuristic than the Europeans, but they still haven’t adopted Japanese washing toilets in significant numbers, and so their quality of life has suffered in small ways that, having never experienced the luxury of this foreign technology, they cannot even comprehend.)

Whatever the reason, the resistance to AC technology is making Europe a more impoverished civilization. It’s a major reason why Europe now feels shabbier and more hardscrabble than America, despite its beautiful old cities and low crime rates.

Europe needs to emulate societies that embrace the technological future. Japan is a good one, but an even better example might be Singapore. That city-state’s legendary founder, Lee Kuan Yew, believed that air conditioning was the crucial technology that allowed his country to become one of the richest on the planet:

“Air conditioning was a most important invention for us, perhaps one of the signal inventions of history. It changed the nature of civilization by making development possible in the tropics.

Without air conditioning you can work only in the cool early-morning hours or at dusk. The first thing I did upon becoming prime minister was to install air conditioners in buildings where the civil service worked. This was key to public efficiency.”

Europe would do well to listen to his advice.

Absorption of foreign technology simply makes the difference between a poor society and a rich one — between a technologically advanced society and a backward one. Most countries have their blind spots here, but Europe’s spasmodic rejection of air conditioning is far more costly than most.

This is actually a bit of an overestimate, since the European households who already have AC are probably ones who need it more.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Noah Smith

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://noahpinion.substack.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.