The economic reform roundtable has descended into farce. Not content with hand selecting people to largely glaze the ruling party, the government also banned cameras and recordings! A cynic might think that the outcome were preordained and the government were obsessed with controlling the narrative.

But, despite the shemozzle that is the roundtable, Australia has very real problems.

Australia has a budget problem. It is spending more than it is raising. The government is scrambling for money and talks of “tax reform” have gathered steam. To this end, parliament recently hosted a “tax roundtable”, in which “experts” proposed that CGT be raised and additional taxes imposed on trusts. The ACTU has now called to hike CGT as well.

There are many proposals to unpackage. But, let’s focus on the CGT one: CGT is most frequently misrepresented, often by people who do not invest and have little engagement with financial markets.

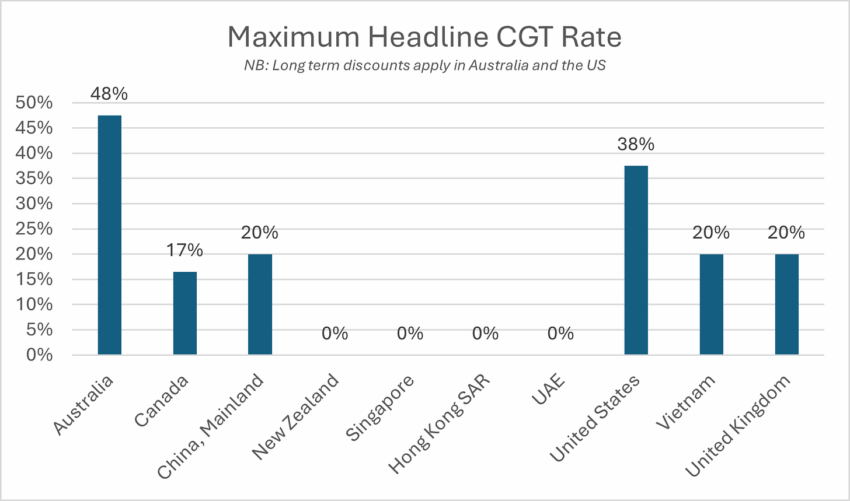

There’s just a tiny problem: Australia has literally the highest CGT rate in the world. Australia’s top CGT rate is currently 47.5%, the top marginal tax rate. Many people obtain a 50% capital gains tax discount for holding the asset for more than a year. But, even at 23.75%, Australia’s rate far exceeds other countries.

Let’s see how this compares: New Zealand has 0% CGT. But, it’s not just New Zealand. Singapore, Hong Kong and the UAE have 0% CGT rates. Communist run Vietnam and China have 20% CGT rates. In the US, capital gains are taxed at the personal rate, with a 50% discount for long term gains. The tax rates in the US are lower than in Australia and are indexed.

There are simply no other countries near Australia’s current CGT rate. The idea of hiking CGT rates is – to put it bluntly – absurd and insane.

This also illustrates a broader problem with roundtables: the host can select participants to support a foregone conclusion, enabling ideologues to masquerade as “experts” and shutting out contrary opinions.

In this case: the alleged “experts” appear to support a policy that will backfire. Not only that, there is very recent precedent in the UK to evidence precisely this. So, let’s dig deeper into the issues with hiking CGT.

The short of it is that Australia’s CGT rates are already among the highest in the world. Raising CGT rates will result in less tax revenue and stymie growth. This is due to how CGT rates influence investor behavior. Proposals to raise CGT are myopic and ignore the incentive effects of raising CGT. They also ignore that Australia is in a global competition to attract, and retain, capital.

Let’s start with recent precedent: the UK tried this and it failed spectacularly, resulting in less tax revenue as people fled the country. In short, the UK sought to increase CGT to around 20-24% and tax offshore income. Notably, this is still lower than Australia’s maximum CGT rate of 47.5% for short term gains to someone on the highest marginal rate.

The net result of hiking capital gains tax rates in the UK: human and financial capital left the UK. The UK is estimated to have lost at least 16,500 millionaires and capital gains tax receipts fell by 10%.

So why is this the case? Well, it’s Economics 101 and has been known at least as far back as Holmstrom and Milgrom’s seminal 1987 paper. Both Bengt Holmstrom and Paul Milgrom went on to win separate Nobel prizes. Their paper models the situation where a company’s value depends on the ‘effort’ of its employees. They highlight that incentive compensation contracts induce effort, enabling both the company and the employee to grow wealthy together. They also emphasize that the employee will only work if the incentive contract pays them at least a ‘reservation wage’, which is at least as good as their outside opportunities (i.e., other jobs), and compensates them for the effort they make.

There are clear insights for CGT. Australia’s GDP grows with investment. But, it will only get investment if investors feel the after tax returns to them are sufficient. And, when considering this, they will consider whether it is worth moving overseas, which is significantly easier than it once was.

Australia must be extremely careful about increasing CGT lest it deter investment, and lead to capital flight. Let’s illustrate several key issues.

Australia must have regard to CGT in other countries. Australia must not be complacent or arrogant and think that it is entitled to, or guaranteed, capital investment. Human and financial capital is more mobile than ever. This is a significant issue for Australia as its CGT rates are among the highest in the world. Notably, myriad locations have 0% CGT. These include Singapore, Hong Kong, and the UAE. More importantly, they include New Zealand, which is but a short flight away. In short, Australia risks significant capital flight to New Zealand. Australia is already unable to attract significant capital.

Australia still has some capital activity. This is because on an after-tax basis there are still some good opportunities and there are inherent frictions in moving overseas. However, Australia is doing worse than it would otherwise do.

Australia could counter this trend by cutting CGT. In so doing, it can attract more capital relative to its already high CGT rates. Furthermore, it can stem the flow of capital overseas.

But lowering CGT gets better! Lower CGT means more transaction volume and transaction frequency. At present, people wait one year and a day to get the long term capital gains tax discount. But, this grinds transaction frequency slower, in turn reducing total tax revenue. Instead, consider a situation where all CGT were 15%. Well, it only takes two transactions to raise more revenue than the current long term rate of 23.75% for the top marginal tax payer.

Raising CGT will slow transactions, reduce transaction volume, and reduce total revenue. Think of it this way. The current long term CGT discount is 50%. A proposal is to reduce that to 30%, or eliminate it entirely. So, consider a situation where someone bought a house for $1m, and is considering selling it for $1.5m, perhaps for another investment opportunity. Currently, they would pay approx. $120k in tax if they are on the top marginal tax rate. This reduces their equity from $500k to $380k, which falls again if they must pay stamp duty on the next investment. By contrast, if the long term discount falls to 30%, their equity falls to around $333k. If the long term discount is eliminated, the equity falls to $263k. The net result is that the next transaction must be even more attractive for it to be worth selling, resulting in fewer transactions; and thus, less revenue.

And this is to say nothing of the impact on economic growth. If, as indicated, capital leaves Australia (or fails to come to Australia), it is easy to see how this will impact growth. This is financial economics 101. If there is less capital available, then capital rationing will occur. Projects that might otherwise have been good will simply not be funded. The result: less economic growth, and with it, less tax revenue.

Where does this leave us: hiking CGT rates is self-defeating. It risks reducing overall tax revenue and overall economic growth. Any talk of tax reform must consider incentive effects and must consider how Australia with other countries. It must also take a “pie growing” mindset, with the goal of increasing the economic pie rather than merely carving up a stagnant one.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Mark Humphery-Jenner, PhD

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://financemark.substack.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.