Asa Briggs once came to my school to inspect the Combined Cadet Force (CCF). In retrospect, this should have surprised me in at least two respects. First, that a famously swotty Outer London day school maintained a CCF — albeit voluntary — at all (one schoolmate thought that weapons training might usefully prepare him for the service he planned in the IDF; in fact, he became a theatre director). Second, that Professor and soon-to-be Lord Briggs, then vice-chancellor of Sussex University and the nonpareil grandee of British liberal institutions, should want to take salutes from pimply schoolboys in makeshift uniforms.

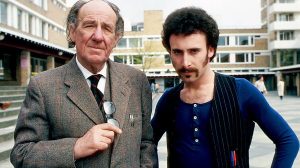

Back then, in the early Seventies, both the school and Briggs himself comfortably inhabited parallel worlds. The school bussed suburban kids from semis in Finchley or Edgware to its rolling acres (much used for TV shoots) not far from the Elstree Studios. As for Briggs, the great popular historian and tireless educational entrepreneur trailed a discreetly glorious military past as a backroom war winner. A code-breaker in Hut 6 at Bletchley Park, he had become the youngest warrant officer in the British army and once held (improbably enough) the rank of Regimental Sergeant Major (RSM). When, in 1945, the fellows of Worcester College, Oxford learned that their incoming young colleague was an RSM, some feared a roaring moustachioed martinet. What they got was a short, rather tubby and affable Yorkshireman.

Briggs, and a handful of other figures of his kind, loomed over my youth like secular divinities. Thanks to him and his influence, in the sixth form I scrutinised the prospectus for Sussex as if studying a tourist guide to Shangri-La. Although other, equally glamorous, citadels of the “plateglass” sector that Briggs championed appealed almost as much (York! Kent! East Anglia!), my teachers put an end to such fancies and sent me briskly down the “ancient university” track. I still have twinges of regret about missing Sussex and its boundary-busting, interdisciplinary studies in its almost-prime — although, with 20 applicants then vying for each arts place, it might well have found me wanting. Those pangs hint at the charismatic spell that Briggs and his ideas, for a while, could cast.

At that time, Asa Briggs from Keighley, via Bletchley Park, Oxford and Leeds Universities, embodied the postwar Great and Good with a bumptious confidence and charm. Historian David Cannadine called him “the Macaulay of the Welfare State” and Tristram Hunt (now director of the V&A) “the last great Victorian improver”. Around the time that he descended on my school to bless a parade of boy soldiers, he was not just running Sussex and juggling (as usual) half a dozen books. He had recently chaired the Briggs Committee on nursing and midwifery. Enacted from 1979, its proposals transformed nursing education more thoroughly than any changes since the age of Florence Nightingale.

Committed to Sussex, he was batting away juicily prestigious job offers — Oxbridge college headships, an assistant directorship at Unesco in Paris (Richard Hoggart, fêted author of The Uses of Literacy, got that), the inaugural direction of the European University Institute in Florence — as lesser mortals swot flies. Meanwhile, the BBC not only paid him a hefty annual stipend to trudge through his multi-volume History of Broadcasting in Britain (five parts, 1961-1995) but funded an entire research unit to support it. He wielded, it seemed, an almost-occult power not only to refresh the past — in widely-read and enjoyed books such as The Age of Improvement, Victorian Cities and Victorian People — but to reform the present. No wonder the slightly rotund scholarship boy from the West Riding inspired not simply respect but a kind of awe. Even Iris Murdoch had once fallen in love with Briggs. “You rational romantic,” the novelist purred. “Without your cool head nearby, how can I see the world properly?”

An entire generation, or two, came to feel that way. Adam Sisman’s new biography, The Indefatigable Asa Briggs, has a title that makes him sound like a Victorian battleship (how apt!) but otherwise supplies a full, fair, if kind, account of life and work. Sisman, whose past subjects include John le Carré and AJP Taylor, rightly dubs him a “progressive moderniser”. Ennobled in 1976 (along with his friend Benjamin Britten), he sat as a crossbencher; it was thought that the avid first-class seminar goer and lecture giver should have taken the title “Lord Briggs of Heathrow”. In a confidential testimonial, an Oxford friend once wrote that “He is not at all a dottily radical figure but he does believe in a fair society.” But his moderately Left-of-centre stance never stopped him from fronting a cross-party post-1945 programme of educational and cultural expansion built on the solid rocks of full employment and the welfare state. Those rocks began to erode in the Seventies, and with it the world that Asa and his bustling fellow improvers made. In a 1985 assessment, written in the heyday of Thatcherism, Cannadine noted that “the march of events has transformed Briggs from being a conformist into being a dissenter”.

In the Eighties, after he had returned to Worcester as Provost (he retired in 1991), Briggs had added to his bulging portfolio of trusteeships a post as chair of the Church of England’s Advisory Committee on Redundant Churches. By that point, he looked in danger of becoming a Redundant Church himself: his congregation dwindling, his monuments in disrepair. The meritocratic liberal mandarin class he embodied had run out of road, and of puff. The consensus they had nurtured — a conviction that high tax revenues should fund both robust public services and ever wider opportunities for the next generation — frayed or crumbled. Their national story of social and cultural uplift for the many (but not that many, by 21st-century standards) now faced challenge by critics who saw it as a sentimental fable to mask long-term economic stasis. Noel Annan — a far more patrician figure than Briggs, but one who shared the Yorkshireman’s institutional values and skills — rounds off his terrific 1990 elegy for this generation, Our Age, with a plaintive chapter entitled “Our vision of life rejected”. A whole generation further on, Sisman’s life of Briggs lets us see whether that rejection actually happened — and whether it would have been correct.

I had expected Sisman to confirm a familiar narrative: that the more-or-less centrist, “Butskellite”, overlords of the postwar welfare-and-education state found themselves humbled by Thatcherites and free-marketeers, red in tooth and claw. To a degree, that did occur. By 1992, even ever-supportive Auntie BBC — with John Birt its cost-cutting director-general — had shut down Briggs’s research office. When he had published a digested single-volume history of the Corporation, alpha columnist Peter Jay mocked its author in The Times as “the Venerable Briggs”, “meticulous, uncritical, unilluminating, shy of issues, and immensely boring”. The times, and The Times, had changed. But Sisman shows as well that Briggs and his critics in the final decades of the 20th century had more in common than they often suspected. In 1990, Annan could see only rupture and rejection. In 2025, the “liberal elite” of the time and their conservative detractors look more like fractious cousins than warring tribes.

Nothing illuminates this kinship better than the extraordinary history of Briggs’s six decades of association with Rupert Murdoch. With Briggs a junior history don at Worcester, and Murdoch the low achieving undergraduate son of an Australian newspaper boss, the pair and other friends drove around Turkey in 1951 in Murdoch’s new Ford Zephyr. Briggs then coached Murdoch so that the Australian scraped a Third, after his father’s sudden death had wrenched him from his studies. Thus a “permanent bond” formed. After all, the lad from Keighley Trades and Grammar School had no more time for upper-crust “snobbery and condescension” than the upstart Antipodean.

The pair kept loyally in touch: Murdoch came to Briggs’s landmark parties, and flew in for his memorial service in 2016. Amazingly, for those who like to picture British society in comforting binary diagrams, Murdoch actually negotiated his purchase of the News of the World — his crucial breakthrough into UK newspaper ownership — while staying with Asa and Susan Briggs in Lewes. The current proprietor lived nearby. Briggs’s daughter, Katharine, started to worry about the phone bill the wannabe tycoon was running up. Within months, Murdoch had added The Sun to his nascent empire. Historians with a taste for hyperbole might argue that the foremost intellectual advocate of the postwar progressive state had nurtured its principal mass-media gravedigger.

But then Briggs, like many of his coevals, pursued reform more as a spirit than a doctrine. That spirit certainly never ruled out commercial ambition. His erudite interest in Victorian entrepreneurship — above all, in relatively egalitarian Birmingham — made him the house historian of choice for companies who sought a scholarly but sympathetic record of their past. Marks & Spencer, Longmans publishers, Lewis’s department stores, Victoria Wines: Briggs picked up generous fees for these projects (up to £200,000 each, in 2025 values) even if he missed the deadlines for years on end. He had himself grown up a grocer’s son who served behind the counter, although Willie Briggs’s Keighley store went bust and ruined the family’s finances. And when another grocer’s child took power, in 1979, his political distance from her was modified by a kind of temperamental affinity.

In 1985, when Oxford dons rejected the award of an honorary degree to Margaret Thatcher, the Provost of Worcester privately called the vote a “terrible mistake”. Each may have defined “Victorian values” in different ways; for Briggs, they mandated a proud public sector and social solidarity. Still, four decades later, their generational bonds make the political opponents of this cohort look increasingly alike. The admirers who gathered at Briggs’s retirement parties in 1991 included not only Rupert Murdoch but Isaiah Berlin, Richard Attenborough, Hugh Trevor-Roper, Roger Bannister and John Sainsbury — the grandest grocer of all, and a close friend since undergraduate days.

It could be that Murdoch and his fellow disrupters of the Thatcher and post-Thatcher period needed the world that Briggs and his peers had built; just as young Rupert needed Asa to steer him through exams to a degree. They kicked against the institutions the Briggsians had laboured to edify, from Sussex University itself to the BBC, the NHS, and every cultural pillar of the age. Yet their critique tacitly assumed that the walls would hold against the onslaught. Thatcher herself never “dismantled” the post-1945 welfare state; as a journalist who covered the public sector in the Eighties, I can testify that economic de-industrialisation made it busier than ever. As for The Sun, and even The Times, without the resilience of the Venerable Briggs and his kind, they would have shot their barbs of scorn into thin air. It is a moot point whether the supposedly radical conservatives of the pre-millennial decades really wished to wreck the system Briggs did so much to create, or whether their heirs want to do so now. If so, they would have to own the consequences. When universities of the sort that Briggs fostered start to close, we’ll begin to know.

For now, much of his legacy endures. If Sussex has lost its lustre (although even in the Sixties he had to defend controversial speakers against “deplatforming”), the Open University — which he helped plan, and served as Chancellor for 16 years — faces few calls for abolition. At the BBC, the entirely Briggsian figure of David Attenborough (brother of Asa’s good mate Dickie) commands oceans-deep public esteem. Briggs aimed to fling open the doors of knowledge, and he did. Forever in transit, perpetually overcommitted, the “Galloping Professor” sometimes emerges as a figure of fun in Sisman’s able hands. “What is the difference between the Lord and Lord Briggs?” Trevor-Roper quipped at Oxford. “The Lord is always with us.” Malcolm Bradbury guyed him as the trendy trimmer Millington Harsent, vice-chancellor of the “University of Watermouth”, in his campus satire The History Man. But he helped huge numbers to travel further, and reach higher, than ever before. If that model of “improvement” is kaputt, Briggs and his crew did not smash it.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Boyd Tonkin

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://unherd.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.