The blogosphere is back! In the early 2010s when I started writing, there were tons of interesting debates carried on between blogs — one person would write a post, and someone else would link to it and respond to it on their own blog, and they’d go back and forth for a few rounds. It reminded me a little of the “Republic of Letters”, the network of intellectual exchange that existed in Europe and the Americas in the 1600s and 1700s. In the mid to late 2010s, this epistolary exchange was superseded by Twitter fights; instead of slow, measured responses, intellectuals would “dunk on” each other with 280-character denunciations. Something important was lost.

But I’m happy to report that with the degradation of X and similar platforms, and the rise of Substack and other new blogging utilities, we’re starting to see some of the old debate style return. A good example is the recent debate over whether moderate Democrats are more electable. So in traditional blogosphere fashion, I’ll try to give a rundown of the debate itself, and then see if I can add anything new.

Run moderate candidates, or turn out the base?

This argument has been simmering for a long time (perhaps for centuries), but recently a new crop of analysts has started to bring new statistical methods to bear on the question. Since the late 2010s, political scientists have begun to borrow a concept called “wins above replacement” from sports. Sports WAR is fairly complicated, since it involves isolating a single player’s contribution from the contributions of the rest of the team. But elections are an individual sport; when political scientists talk about WAR, they really just mean doing some regressions on election results to figure out what individual characteristics cause candidates to outperform.1

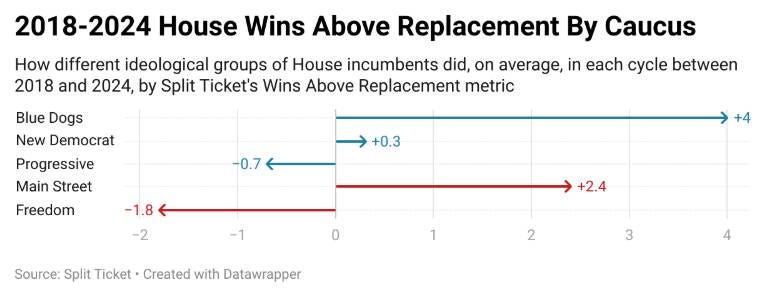

A data analysis company called Split Ticket, headed by Lakshya Jain, is probably the most famous for using this methodology. They’ve consistently found that moderate candidates do better than strongly ideological ones on both the Democratic and the Republican sides. For example, here’s a chart where Split Ticket breaks out recent performance by Congressional caucus:

This seems pretty solid, but it’s subject to a subtle caveat. Split Ticket tries to control for every important feature of a Congressional district that might influence the outcome of elections. But there might be interactions between those characteristics and a candidate’s level of moderation. For example, Blue Dog Democrats might outperform in their own districts, but if you plunked them down in the districts that elected AOC or Ilhan Omar, they might do even worse than those progressives. It’s hard to say. But this is sort of a second-order problem; these results still suggest that Democrats should try running more moderate candidates.

Some political scientists have disagreed with this conclusion. For example, Bonica et al. (2025) use an alternative methodology to assess the benefits of moderation. They measure candidate’s ideology based on a combination of how they vote in Congress and which donors donate to them.2 They find that moderation is beneficial, but the benefit is smaller than what Split Ticket finds. Bonica and his co-authors argue that this means that base turnout is ultimately more important, and that politicians should therefore be unafraid to embrace strong ideology in order to fire up the base. Here are some excerpts from a thread Bonica wrote:

This conclusion has a major problem, and hopefully you can already see what it is. Suppose a researcher comes to you and tells you that people in hospitals are more likely to die of disease than people outside of hospitals. Should this make you avoid hospitals when you’re sick? No, of course not. People go to hospitals because they’re sick, so of course those people are more likely to die of disease!

Similarly, Bonica’s observation about Democrats’ national election performance interprets correlation as causation, when there’s an obvious reason not to interpret it that way. Obama won in 2008 running a campaign that was more lefty than usual, and won. But maybe he was able to run on a more lefty platform precisely because the electorate was in a more lefty mood than normal! After all, voters in 2008 were very mad about the Iraq War and the financial crisis. Obama harnessed that anger to win, and the anger also caused high turnout.

But in 2010, the electorate was in a far more conservative mood, and brought in the Tea Party Congress. Democrats ran to the center that year, and still lost big. But they might have run to the center precisely because the electorate was in a conservative mood! And had they not run to the center, their performance in a conservative-leaning year might have been even worse!

Kamala Harris tacked to the center in 2024 and still lost a fairly close contest. But suppose Kamala Harris had come out as a progressive fire-breather in 2024, the way she tried to in the 2020 primary. Suppose she had railed against systemic racism, called for an end to military aid to Israel, proposed cutting police budgets, and offered a full-throated defense of Biden’s tolerant immigration policies. Do we really believe that this strategy would have kept the election as close as it was, or even won it by turning out the base? That’s what Bonica and his co-authors would have us believe. And though we can’t prove them wrong, it doesn’t really pass the smell test, does it?

Of course the WAR analyses for congressional races also don’t separate correlation from causation. But because congressional analyses look at the characteristics of the candidate and not just of a particular election year, they’re much more robust to this kind of obvious reverse-causation. In other words, Bonica’s call for Dems to ignore the persuasive benefits of moderation and focus on turning out the base rests on extremely shaky assumptions. The benefits of moderation at the candidate level are a lot more well-established than the benefits of turning out the base with ideological appeals.

Anyway, the debate over moderation picked up again recently, when G. Elliott Morris released the results of his own WAR measure:

Like Bonica et al., he found that moderation is correlated with electoral victory, but that the effect is a lot smaller than what Split Ticket finds — maybe a one percentage point bonus instead of four, relative to the median Democrat. His conclusion is that the benefits of moderation have been overblown.

Matt Yglesias took issue with that conclusion:

First, he noted that even a small benefit of moderation is worth trying to take advantage of, and that Democrats should acknowledge this more. Morris fired back, arguing that when statistical uncertainty is so great, we shouldn’t put a lot of emphasis on something like moderation, when it’s so easily swallowed by the noise.

Yglesias also argued that moderation isn’t well-captured by the typical measures, and that the important part of moderation is to take strong iconoclastic stances on a few hot-button issues, instead of voting with the party most of the time or taking money from lefty donors. Finally, Yglesias claims that the Democrats as a whole would benefit from moving to the center, so that individual moderate Democratic candidates could reap the benefits of their moderation without being saddled with their party’s extreme stances. These are interesting arguments, and they might be true, but they need to be validated with data.

Meanwhile, Jain and Bonica continue to debate the value of their respective measures of “wins above replacement”. Bonica and another political scientist named Jake Grumbach argue that Split Ticket essentially fudged their numbers, introducing secret “adjustments” to their regressions to put their thumb on the scale for moderates; Jain replies that the adjustments are tiny and don’t affect the main result. Here Bonica and Grumbach have a good point — Split Ticket should make the adjustments explicit — but it probably doesn’t drive the result.

Bonica and Grumbach also argue that Split Ticket didn’t control for enough variables in their construction of WAR. They use a machine-learning model to predict electoral victories with a high degree of accuracy, and conclude that because the residual of that model is small, moderation isn’t very important. But the machine-learning model is basically mystery-meat — the variables it’s using to predict candidate victories might be strongly correlated with moderation, in which case moderation is important.

Bonica and Grumbach would seem to be on more solid ground with a new working paper entitled “The Electoral Effects of Candidate Ideology in the Trump Era”. They show screenshots of this paper in their blog post, and discuss its methodologies. One of these methodologies — looking at close primary contests between progressive and moderate candidates as a sort of randomized trial — seems very promising. But unfortunately, I can’t find the actual paper online; the blog post claims it’s on Grumbach’s personal website, but I can’t find it there, or anywhere else. So we’ll have to wait and see what turns up there.

So far, the pro-moderation side seems to be getting the better of the debate, but only slightly. Running more moderate candidates seems to convey a small benefit. But much more important is the overall stance of the Democratic party and of Democratic presidential nominees, and here the data just doesn’t tell us very much. It’s a bit like macroeconomics versus microeconomics; the former is the only way to answer the big questions, but it’s so confounded that it’s hard to get solid answers.

Moderate policies are usually better for the people

This is an interesting technical debate, with some pretty high stakes. Winning elections is very important, as the consequences of Democrats’ defeats in 2016 and 2024 have made plain. But at the same time, we live in a representative democracy, and politicians aren’t perfect avatars of the popular will; they have a lot of leeway to make policy choices that are better or worse for their constituents. And they have a moral responsibility to help their constituents instead of hurting them.

Politics matters, but policy matters too.

And when it comes to policy, moderation tends to produce better results. This is because the effects of policy are highly uncertain; when you make big changes to the status quo, it’s a lot riskier than making small changes. Sometimes you need to take big risks — for example, in a war or other acute emergency, where the status quo will clearly lead to disaster in a short space of time. But most of the time, and along most dimensions, the world isn’t in an emergency, and so you should take risk into account.

That doesn’t mean big policy changes are always bad; often, they’re the right thing to do. It just means that unless you’re in an emergency, you should be careful about making big abrupt policy changes, and you should demand clear and compelling reasons before making them. In other words, moderation isn’t always the answer, but it has some value.

An example was fervor for police defunding in 2020. A lot of progressives, including Kamala Harris, AOC, and Zohran Mamdani, called for deep cuts to police funding. But the balance of evidence strongly indicates that a robust police presence is very important for deterring crime. And logic and evidence make the mechanisms of this deterrence clear — more cops means crime carries a greater risk of arrest, cops deter crime in public spaces just by standing there, and cops physically remove hardcore criminals from society.

Harris, Mamdani, and the other Democrats who hopped on the activist bandwagon in 2020 should have been more circumspect. Not only did this turn out to be bad politics, but it was bad policy as well — and a rapid return to more robust police presences probably helped tamp down the crime wave of 2020-21. Even if Democrats could have won some elections in 2020 by yelling “Defund the police”, the few cases of actual police defunding probably resulted in more Democratic constituents getting killed.

Another example is fiscal policy during the pandemic era. The CARES Act during the pandemic was radical, and was good policy overall — but that was an emergency, where doing nothing clearly would have resulted in personal financial devastation for millions of Americans. In 2021 the danger of devastation had receded, yet Biden still passed a very large pandemic relief bill. Moderates like Olivier Blanchard warned that a bill of this size would lead to inflation, but these warnings were ignored. And Biden’s American Rescue Plan probably did lead to increased inflation, bringing down real incomes for millions of Americans. That had negative electoral consequences in 2024, but it was also just bad for regular people.

A third example is housing. Most cities have seen a dynamic emerge where the “progressive” position is to largely block new housing development, while the “moderate” position is to allow new development. Although the electoral benefits of YIMBYism versus left-NIMBYism are not yet clear, the evidence is strongly in favor of the more moderate position as being more conducive to housing abundance. And where politicians try it, it almost always seems to work. Winning elections is important, but people having somewhere to live is intrinsically a valuable thing.

Of course, good policy and good politics aren’t naturally at odds — in fact, in the long run, the two goals are probably aligned. We hope that in the long term, electoral outcomes and policy outcomes roughly align — i.e., democracy works if people know what’s good for them and eventually elect leaders who give them what they want. In their book Abundance, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson make a persuasive case that if progressives can’t deliver real results for people, people will eventually abandon progressivism. Hearteningly, some progressives are taking this admonition to heart, and embracing policies that previously might have been seen as too “moderate”.

Some ideologues have argued that adopting extreme policy positions is a way to “move the Overton Window” — that unless you start from an extreme first offer, you can never negotiate your way to a more moderate change. It’s a thesis that deserves investigation, but recently it doesn’t seem to have been working very well. Socialists demanded a total ban on private health insurance in 2016 and 2020. But what they got wasn’t a more moderate public option or expanded Medicare coverage — it was total defeat. The American electorate, seeing unreasonable demands, basically decided to ignore further health reforms completely, robbing Democrats of a key issue and tabling further efforts toward government health care indefinitely. Even if you think government health care is good, this is a bad outcome.

On sociocultural issues, there is a tendency to sneer at the idea of moderation, due to the memory of the Civil Rights Movement. At that time, moderates cautioned the nation to go slowly on desegregation, but activists pushed ahead and won big reforms anyway. If you agree that desegregation was good (which you should), then this is a clear case where moderation wasn’t the right course. But that case doesn’t generalize. There’s no reason to think that just because racial segregation was bad, that therefore trans women should be allowed to play on women’s sports teams and change in women’s locker rooms. In fact, I don’t know if those things should be allowed or not. But it’s a mistake to think that the long arc of history bends toward whatever progressive activists are currently pushing for.

Right now, it’s the MAGA right that’s making policy, not progressives. And from mass deportation to tariffs to defunding of scientific research, we’re once again going to encounter the downsides of extremist policy and the benefits of moderation. Public opinion, realizing this, is already turning against MAGA’s excesses.

In this situation, it’s natural for Democrats to think more about how to win the next election than about what kind of policies would benefit the citizens of the United States. But unless Dems embrace moderation before winning back power, I fear we’ll just see another round of ping-ponging between two extremes, with Americans getting increasingly more disillusioned each time. Moderation doesn’t mean going easy on Trump — it means attacking Trump hard, but also planning a replacement regime that will be sensible and effective instead of reactive and ideological.

“Do the stuff that works” is simply a good approach to governing a country, and one that America’s political class used to value more than they do now.

Basically, this is just a two-stage regression. First you regress candidate wins on a vector of electorate-specific observables like partisan voting history and presidential vote share in the same year, then you label the residual “WAR”, then you regress WAR on various candidate-specific observables like ideological moderation, in order to predict which individual candidate characteristics are correlated with higher win probabilities. The name “WAR” seems to be used mostly for marketing purposes. But hey, as a researcher, you need to get your ideas out there!

Lakshya Jain criticizes this measure of moderation, because he says it doesn’t do a good job of measuring stances on social issues, and thus focuses too much on economic issues.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Noah Smith

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://noahpinion.substack.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.