Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s latest film, About Dry Grasses, was released in the UK last summer. Terrible timing. I’m surprised they went ahead with it given the high-quality competition swarming around: the Paris Olympics which demanded about eight hours of concentration each day, European football championships in Germany (ditto), Wimbledon (probably even more). All that sport-watching was taking up a lot of time, and the film, with its inordinate run-time of over three hours, was going to take up even more.

All films today are too long, irrespective of how long they are. You sit there and think to yourself, in real time, as it were, how easy it would be to trim off bits here and there, 10% or 15% overall — and, in a lot of cases, 100% in total — with no loss at all, only an overall improvement in quality. Even Anora, which is a lot of fun, suffered from a kind of serial redundancy in that extended sequence where they’re driving around to about 50 different joints looking for the little Russian brat-punk, energy draining from the picture with each stop. Clocking in at precisely 197 minutes (why didn’t they add another three minutes and round it up 200?), About Dry Grasses was like the Japanese fleet in the Battle of the Philippine Sea: at the extreme limit of my fuel, so even when all the sport on telly had come to an end, it still took an effort of will to get out of the house and into a cinema — the number of places it was showing had, by then, shriveled considerably — with very comfy reclining seats and plenty of leg room. This piece is a kind of one-year anniversary celebration of that evening in the middle of August when my wife and I schlepped into the West End, to the Picture House Central.

We were always going to go because Ceylan is not only a master, obviously, but a very funny one too. I pride myself on never having laughed during any film by the witless Coen brothers. Why? Because I have a sense of humour. Laughs in Coen films are just for laughs. They have a reputation as auteurs, those bros, but their films are more frat-house than art-house. Bong-water humour. Ceylan has a sense of humour in the more highly evolved — i.e. deeper-rooted — sense of a comprehensive worldview, a worldview that is pretty much restricted to Turkey, to Anatolia in particular — but it’s all-encompassing. There’s something funny going on most of the time, either in the centre or lurking around the edges. I’ve no desire to go there, to Anatolia, which frankly looks like a bit of a shithole, but if I did at some level I’d be happy because it looks like the kind of place where you can have a bit of a laugh — have to have a lot of a laugh, actually, because otherwise life would be unendurable, which it might still be even with the laughter thrown or, more accurately, built in.

Needless to say, when I say Ceylan is funny I mean he’s deadly serious, as serious as Mahmut, the intellectual and photographer in his 2002 film Uzak. Mahmut lives in Istanbul where he is obliged to host Yusuf, a clodhopping relative who has lost his job in a factory. Yusuf sits there, bored out of his mind, as they watch Tarkovsky’s Stalker on TV, the long tracking sequence where the three travellers take the little engine into the Zone. When the provincial visitor can’t take any more of this unbelievable tedium he trudges off to bed whereupon Mahmud flips off the Tarkovsky and settles down to some serious girl-on-girl porn — which he then has to hastily switch off when Yusuf makes an unexpected return to the living room. The humour is not at anyone’s expense, it’s free in the same way that the air we breathe is free, so even if it’s toxic you can’t expect a refund which, incidentally, my wife and I did manage to get from the relevant box offices after watching 20 minutes of Dune (at an Imax) and 30 minutes of David Fincher’s The Killer on the grounds that they were not fit for adult consumption.

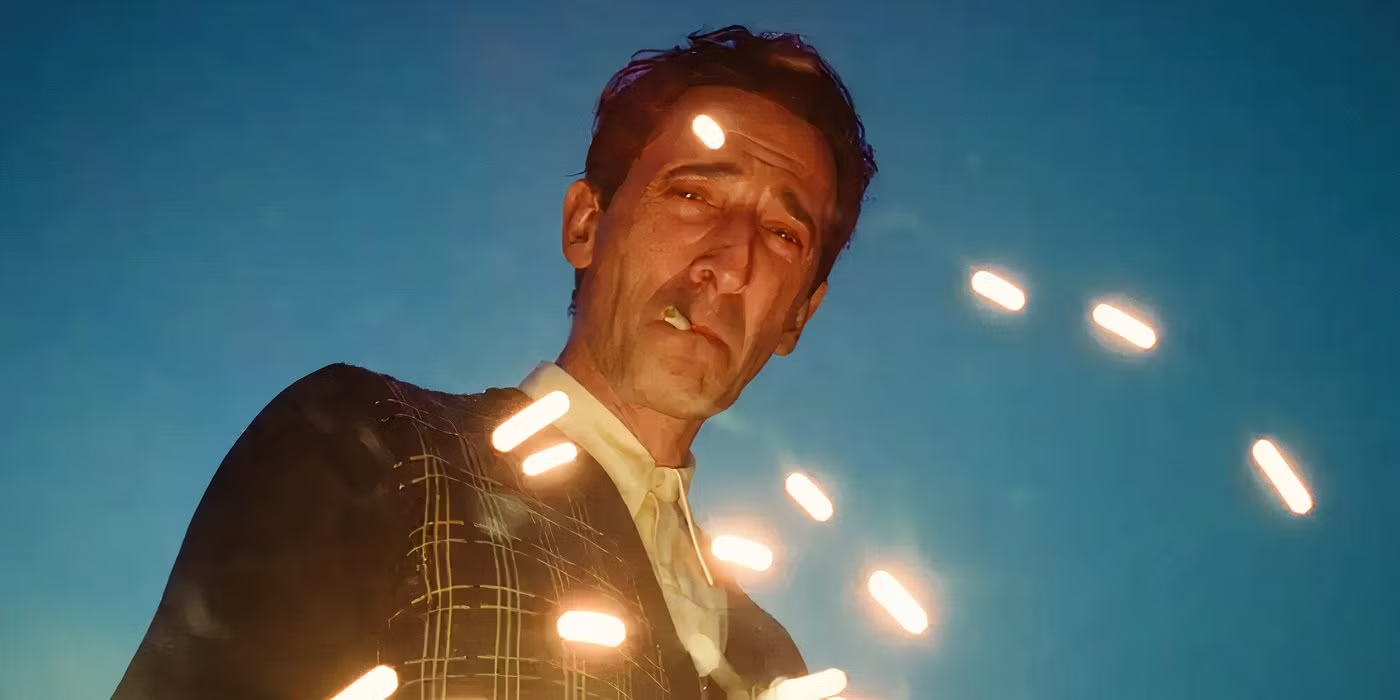

Unlike Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (2011) — which really puts the dead in deadpan — About Dry Grasses isn’t laugh-aloud funny. But it declares the film-maker’s stylistic signature instantly, opening with one of those wide-screen shots of a figure emerging out of a white blankness of snow. From that moment, I was able to relax, thinking, “Yeah, I’m glad I’ve come.” The figure we’ve seen coming out of the snowy nothingness is Samet, a teacher returning to a school in a remote village, a place with very few romantic possibilities, where everyone’s more or less pissed off. There’s another teacher, Kenan, and there are rumours of scandals and the possibility of a male teacher having crossed the line — less distinctly drawn here than it is in American universities — with a young female student. Discontent is simmering. Nothing ever quite comes to the boil in this place, but everything is almost boiling over the whole time. There’s a third teacher, an attractive woman called Nuray, who does bring things to the boil in a curious way in that, first of all, Samet tries to set her up with Kenan and then, when it appears that these two are indeed getting on well, conceives a perverse kind of longing for her, for himself: a desire to thwart the very things he’d previously set in motion.

In all and any art, the bigger the theme the more important the details. About Dry Grasses deals with themes so huge I’m not even sure what they aren’t. The greater the work of art the more difficult it is to say what it’s about and this is true, of course, of un-Ronseal-ishly titled About Dry Grasses. That’s one of the things that makes it utterly transfixing — for the most part. Attention drifts during a long ideological debate but it’s then followed by a sequence — a sort of seduction — so intense you have to remind yourself to blink. Or there’s an earlier scene when Samet and Kenan are at a dreary diner, though that word “dreary” is redundant since everywhere in this town is dreary as all hell. They’re there to meet Nuray, the teacher Samet has told his friend he’ll be attracted to. She says she’s interested in Kenan’s face. The weather systems passing through Samet’s face as he registers this, as she takes a picture of his friend’s face, are so complex it would be a useful exercise to slow them down, like Douglas Gordon’s 24-Hour Psycho, to watch them unfold, but that would be futile because it’s not just the changes but the flickering speed of those changes that is so illuminating as to resist illumination.

Often an Oscar for Best Actor goes not for best acting but best impersonating: so Timothée Chalamet, for example, got a nomination for his dead ringer of the young Bob Dylan. Or an actor will impersonate a person with some physical or mental ailment. To paraphrase something Capote said of Kerouac, that’s not acting that’s afflicting. Speaking of affliction, Nuray has had a leg amputated as a result of an accident, which considerably complicates all of the many factors intermingling during the decision-making process of the seduction dinner and its aftermath. I don’t think I’ve ever studied faces as closely as I did those during these scenes. And I was compelled to do so.

In other words, this was the opposite of being bored which means it was the opposite of watching action scenes which bore the living shit out of me. In The Whole Equation, David Thomson writes that in the history of cinema no effect is “as momentous as shots of a face as its mind is being changed”. I’d push this a bit further and draw attention to the face that can’t make up its mind, that perhaps doesn’t know for sure what its owner is thinking, or that is taking pains to make sure that this process is concealed from the other participants in the scene but is somehow revealed to the audience so that the face on screen effectively holds up a mirror to our attempts to work out what we’re seeing, if we are capable of attending closely enough. That, it goes without saying, is worth attending to very closely. About Dry Grasses insists not only that we attend very closely, but that we do so over an uncomfortably extended period of time. As a result time, if you have a comfortable seat, flies by, almost.

Much has been learned — so much that we are unable to process it, partly because nothing is resolved at the end. It’s like life, ongoing. This is in the starkest possible contrast with the pathetically neat little twist at the end of Conclave. And that got an Oscar for Best Original Script! You might as well have an Oscar for Best-Tied Tie or Best-Tied Shoelaces — and even then it would probably go to a pair of slip-ons because they’re easier to get (on and off). The human relations in About Dry Grasses are impossible to unknot; the more you pull at one strand of them, the tighter and more intractable the tangle becomes.

There are other elements to mention briefly. The breaking of the fourth wall — is it the fourth? I forget how many there are and what it is each of them do — that occurs immediately before the sexual negotiation has been concluded. That’s a vertiginous jolt, but I like a little detail here, as Samet washes down a pill of some kind in the bathroom. Presumably in anticipation of the sexual encounter that lies ahead, a precaution because he is not motivated by lust (neither is she) and both parties are of course acutely aware that the amputated leg, the leg that is not there, might play a part in how the sex might unfold. In a sense, they have sex in order to find out — which is often what motivates people to have sex for the first time anyway.

There are plenty of other points that I’d like to check again. But that would mean watching the film on my computer which I’m not prepared to do. I’ll wait for it to come around again on a big screen — and you should do the same — sometime in the future, ideally when it’s part of a complete Ceylan retrospective, when there’s no competing sport on TV. The film earns its size and its length and has elicited a corresponding loyalty on my part.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Geoff Dyer

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://unherd.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.