Most advanced countries are democracies. In most cases, these countries impose heavy taxes, with total revenues often falling between 30% and 50% of GDP. And yet, most people don’t like paying taxes. How can we explain this seeming contradiction?

The mainstream view of both the economics profession and the general public seems to be that a fairly high level of tax revenue is desirable, say at least 25% of GDP. In this post, I’ll take as a given that the institution of taxes is beneficial to the general welfare. My own view is that the world would be better off if most countries reduced the size of their governments to well below 25% of GDP (as in Singapore). But even I am in favor of governments raising a substantial amount of money via taxes. Thus, for the purpose of this post, I’d like to bypass the issue of whether taxes are too high and consider why democracies are able to enact large tax regimes despite the fact that most voters don’t like paying taxes.

I think it’s fair to say that the typical voter has a sort of “not in my back pocket” attitude toward taxes. They would prefer than someone else pays for government services. If they are poor, they might prefer taxes on the rich, and if they are non-smokers they might prefer taxes on cigarettes. My local government in Mission Viejo does not vote to tax local residents and then send the money to Washington DC to fund the military. It is assumed that the federal government will raise taxes for that purpose. Mission Viejo raises taxes for local services like schools and police. But despite this NIMBP attitude, governments in democratic countries raise vast sums of tax revenue. The implication of this is clear, the unpopularity of taxes does not prevent high tax rates, even in democratic countries. The key is the raise taxes at the same level as the benefits that will be delivered. Local taxes for local services and federal taxes for federal programs.

Matt Yglesias was recently asked this question:

It seems probable to me that a major obstacle to YIMBYist goals is that they are unpopular. How do you square your advocacy for YIMBYism with the philosophy of popularism?

He gave an extensive answer, which included these observations:

There are some people who sincerely welcome new development very close to their home, but they are a minority. Most folks, if they could have their way, would like to see lots of construction jobs and plenty of affordable housing and a growing economy and tax base, but also for all that construction to be happening somewhere else. That’s why it’s called Not In My Backyard, not Principled Hostility to Housing.

The problem with NIMBYism in this sense is that it’s literally not a policy that can be done. If a state government could achieve housing abundance, but with none of the abundance occurring in your backyard, you might love that.

But their actual options are “give every locality a veto so nothing gets built” or “reduce local ability to veto so some stuff gets built.” For a long time, politicians seem to have felt that “everyone gets a veto” was the best way to approximate what voters want. Over time, though, the problems with systemic housing scarcity have started to pile up and become more and more obvious, and more and more people are becoming convinced that “less veto everywhere” would actually be a better outcome.

In my view, the biggest barrier to higher living standards is housing (with health care a close second). Food and clothing comprise an ever smaller share of consumer budgets. Cars have become so good that the vast majority of Americans drive what once were regarded as luxury cars. (My Nissan Maxima is vastly better that the Cadillacs and Mercedes of the 1970s or 1980s.) The real price of home appliances has fallen so much that people often just throw them out rather than call a repairman when they have problems. People eat out much more often. For many people, the type of house they can afford is the key determinant of how well they are doing. NIMBY regulations have pushed up the real cost of housing in many areas. Kyla Scanlon recently observed that this was making people unhappy:

John Burn Murdoch points out that young people are extremely unhappy in the Western world because society broke its promise of a home them – there is no faith in the future of the system, so people turn to ripping each other apart.

Housing abundance is highly popular with the public, just as Social Security, Medicare, policemen, firemen and the public schools are popular. But just as most people don’t like paying taxes, most people don’t wish to see new housing built right next door. From this perspective, both government services and housing abundance are collective action problems, which are hard to solve at the individual level. (Once again, I’m giving the standard view, which I only partly accept.)

However, there is one important sense in which this analogy breaks down. Unlike the provision of various government services, housing abundance does not require any affirmative government action. Rather it would require certain types of governments (i.e., state and local governments) to cease engaging in actions that restrict housing construction. The most local level of all is the individual homeowner. At that level, YIMBYism suddenly becomes much more popular. Do I wish to sell my home for $5 million to a developer who wishes to put up a tall apartment building in Mission Viejo? Yes!!

Proponents of local zoning rules will often cite an “externality” argument for government regulations restricting housing construction. But as Yglesias points out, that sort of NIMBYism is internally inconsistent.

A homeowner who freely chooses to sell to a developer imposes negative externalities on their immediate neighbors. A town that restricts housing construction imposes negative externalities on other residents of the state. A state that restricts building imposes negative externalities on the rest of the country. A country that limits immigration imposes negative externalities on the rest of the world.

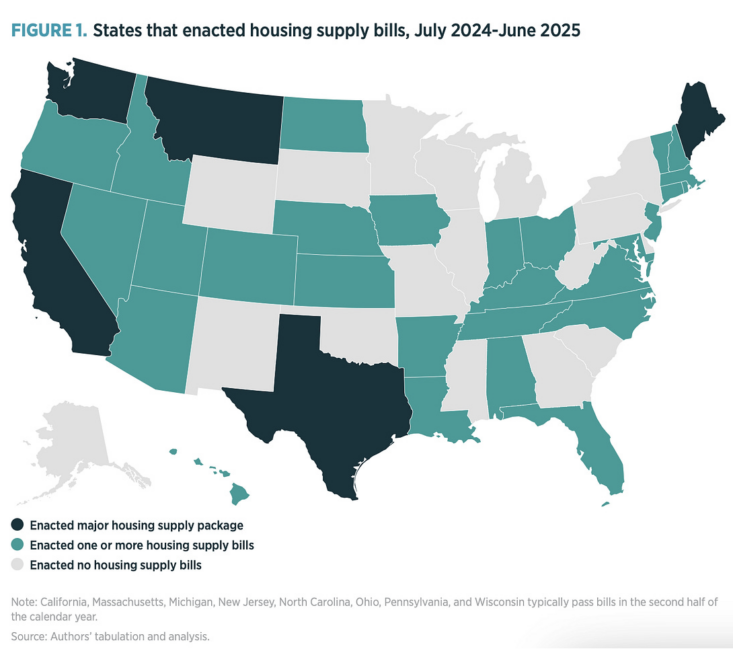

“Popularity” is a tricky concept. A policy regime that is popular at the local level may be unpopular at the state of national level. Just as peoples’ aversion to paying taxes doesn’t mean that democracies will fail to enact substantial taxes, peoples’ aversion to an apartment building going up next door doesn’t mean that YIMBYism will fail in a democracy. Yglesias points out that Yimbys are achieving wins in a wide variety of both blue and red states. His post provides this figure:

PS. A recent study suggests that Los Angeles’ large budget deficit could be closed by building more housing near transits lines.

The post Not in my back pocket (NIMBP) appeared first on Econlib.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Scott Sumner

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://www.econlib.org and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.