California News:

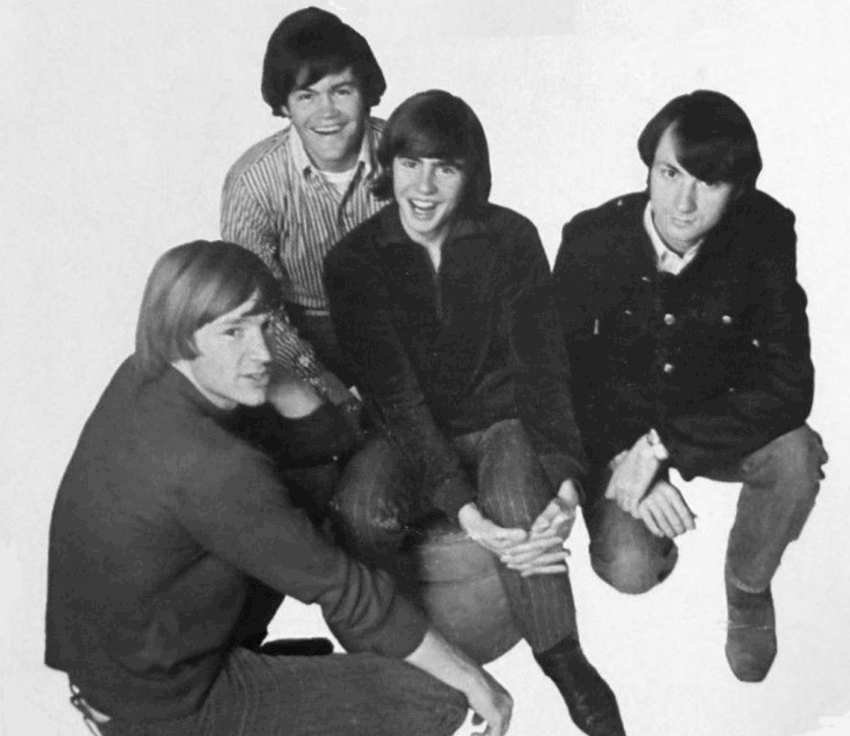

Recently, Grok – Elon Musk’s AI chatbot on X (formerly Twitter) – was widely mocked for responses deemed controversial or offensive. But the fiasco wasn’t surprising. Grok runs on a large language model, and language models don’t create facts or test claims—they mirror what they’re fed, amplifying whatever gets repeated most, whether it’s pop trivia or toxic myths. In one case, Grok hedged on the Holocaust—suggesting the scale of the atrocity was still up for debate, despite overwhelming historical evidence. It was a disturbing example, but not a surprising one. Like all chatbots, Grok is designed to provide helpful responses based on patterns in its training data—not to verify facts. But this phenomenon predates artificial intelligence. Long before chatbots, people accepted falsehoods not because they were plausible, but because they heard them from someone they trusted. In 1967, rock star Michael Nesmith claimed that “The Monkees have outsold the Beatles and the Rolling Stones combined.” It was an intentionally absurd lie, and Nesmith later admitted he said it precisely because it was so easily disproven. Yet the line was picked up by DJs, repeated in fan circles and trade magazines, and quickly solidified into a “fact” people believed—because they’d heard it often, and from the right people. Grok doesn’t evaluate truth. Like a DJ in 1967, it just echoes whatever shows up most—especially from sources it’s been trained to trust. Verification isn’t part of the job. What started as a radio-era prank is now replicated at industrial scale.

Today’s large language models—like Grok and ChatGPT—don’t understand facts; they detect patterns. If a claim appears often enough—especially from sources that sound official—they’ll echo it with fluency and confidence, even when it’s false. A cheeky prank in a Texas radio booth is now standard behavior for AI tools embedded in classrooms, offices, and public discourse. What once made a source authoritative—expertise or evidence—is now replaced by repetition, phrased in polished prose. Even as they warn users that “ChatGPT can make mistakes” or urge them to “check important info,” the systems still present their answers with the tone and structure of expertise—echoing certainty without actually understanding anything. What once fooled fans now misleads policymakers, educators, and the public at large.

This matters—because it’s not just trivia that gets repeated. Policy decisions are increasingly shaped by claims that feel true, sound official, and appear often enough to escape scrutiny. One such claim is that “women earn 77 cents on the dollar compared to men.” Another is that “diverse teams produce better results.” These phrases show up in strategic plans, HR trainings, and mission statements—usually without context, caveats, or data. They sound authoritative—and people either want them to be true, or find them too useful to question. AI systems like ChatGPT are trained to detect those preferences and accommodate them. Ask a politically charged question, and the bot will often reflect back the worldview it thinks you want to hear—polished, plausible, and unchallenging. The result? Flattery becomes a feature, not a flaw. These systems are built to please—rewarded for being agreeable, inoffensive, and smooth. They don’t just mirror what’s most common; they reinforce what’s most comforting. In that way, they help perpetuate the institutions themselves—consensus-driven, image-conscious, and unwilling to entertain contrarian views.

They’re complex issues—worthy of rigorous debate and empirical study. But repeated uncritically, they collapse into slogans: used to signal virtue or suppress dissent, rather than to clarify anything. Even shaky claims can calcify into policy assumptions, not because they’re true—but because they’ve been echoed enough to feel untouchable. As Mark Twain put it: “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

AI tools like Grok are just that—tools. In skilled hands, they boost productivity and improve output. In unskilled hands, they just amplify noise. As the saying goes, a bad workman blames his tools. But a worse one builds with whatever’s lying around—and calls it a masterpiece. AI doesn’t create facts or test claims; it mirrors what we feed it, repeating whatever appears most often, no matter how wrong or self-serving. No legislation will protect us from gullibility. What we need isn’t more regulation—it’s more responsibility. We don’t have to be anyone’s stepping stone—especially not in politics, media, or the next viral myth that sounds just true enough to spread. We’ve heard that tune before. The Monkees are a perfect example.

They weren’t even a real band – at first. They were cast for a TV show and added vocals to songs recorded by the Wrecking Crew – the legendary session players behind countless 1960s hits. But the public believed in them. The records sold. The fiction became fact. Eventually, the actors learned to play, went on tour, and became a real band. AI is following the same arc. It’s not human intelligence—but people treat it like it is. And if enough people believe in it, build around it, and defer to it, the imitation begins to shape reality.

Just like The Monkees, it might become real someday. But we’d be daydream believers to forget it isn’t – yet.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Jim Andrews

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://californiaglobe.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.