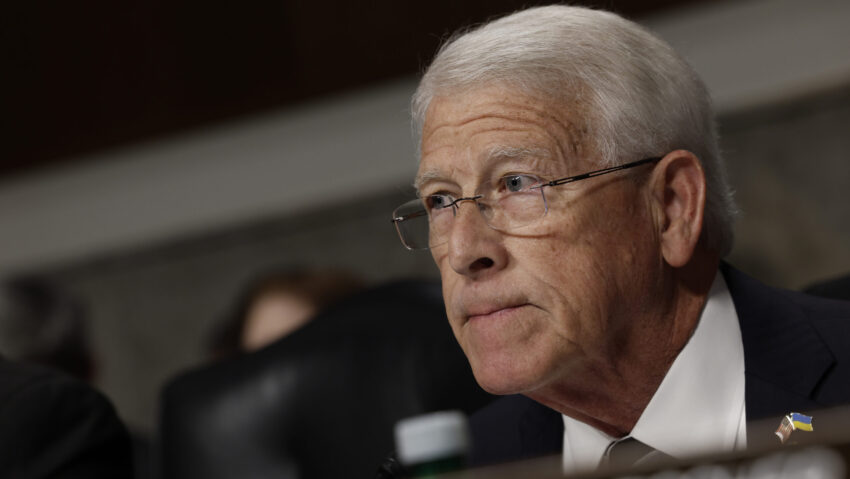

Sen. Roger Wicker (R-MS) speaks during a hearing with the Senate Armed Services Committee Hearing on Capitol Hill on February 15, 2023 in Washington, DC. (Photo by Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

WASHINGTON — With $150 billion in additional funding for defense now signed into law, Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman Roger Wicker is shifting his focus to his other major priority: Enacting a sweeping package of acquisition reform measures meant to shake up the way the Pentagon does business — and potentially putting traditional primes in tougher battles with upstart competitors.

The committee’s version of the fiscal 2026 National Defense Authorization Act, set to be released later today after a week of mark-up activities, will contain acquisition reforms drawn from separate legislation called the FORGED Act, which was designed to ease the regulatory burden on “nontraditional” defense companies and give Pentagon acquisition officials more leeway in how they buy defense articles, according to a senior congressional official.

“While there will be changes to specific elements in language from the FORGED Act, the core tenets are largely there,” the official told Breaking Defense ahead of the committee’s NDAA release.

Like the original FORGED Act, the draft NDAA contains language that defines a nontraditional defense contractor and exempts them from certain regulations. The aim is to increase competition between the large defense primes and smaller, more nimble technology startups and lead to more innovation at a lower price for the US military, while also freeing startups and other firms built on a commercial sales model from onerous rules that often require them to set up separate financial systems.

The bill also would make commercial procurement processes the default contracting method for the Pentagon, and stipulates that nontraditional firms must be treated like commercial entities, according to an initial report of the bill detailed to Breaking Defense.

RELATED: New SASC chair sets sight on $200B defense boost, major acquisition reform push

The bill’s other major pillar would overhaul how the Pentagon’s acquisition corps manages weapons development and procurement, moving from processes centered around programs to ones where officials have more flexibility to made cost and schedule trade offs among a portfolio of connected technologies. That would allow the department to shift money away from underperforming programs or to boost funding for technologies for which there is greater operational demand, all without triggering a food fight among different program offices.

Industry Feedback

The FORGED Act was originally introduced in December, and since then Wicker’s office received more than 50 pieces of feedback from various industry players, with suggestions ranging from specific changes to bill language to overarching recommendations, the congressional official stated.

Not all defense contractors were thrilled about all aspects of the bill. Nontraditional firms were “very supportive” of the legislation, but many prime contractors, “while generally supportive, had some concerns” about how they would be treated compared to the companies classified as nontraditional defense contractors, the official said.

To ease the concerns of the biggest industry players, some changes to the original FORGED Act were made to further adjust the definition of a nontraditional contractor, although the official noted that these were not the more sweeping shifts that defense primes had wanted to see.

“We made certain tweaks, particularly to the definition of a nontraditional, that maintained an ability for the traditional to also be considered [nontraditional] under those circumstances, or have business units that could be considered nontraditional,” the official stated.

Specifically, the bill modifies the definition to include “business entities” that do not have significant research and development or bid and proposal costs reimbursed by the government. The thinking, the official said, is that if a prime is willing to make larger corporate investments to develop new products — the way most commercial or nontraditional defense firms do — they can be designated as a nontraditional for that program.

“The idea of going at risk and not getting reimbursed on certain things is one of the core tenants of what a nontraditional, we believe, should be,” the official stated.

The NDAA version of the acquisition language also more fully fleshes out new rules surrounding test and evaluation, as well as the department’s Modular Open Systems Architecture (MOSA) process — two topics that the original FORGED Act did not delve into deeply, the congressional official said.

The bill amends current MOSA requirements by requiring non-proprietary, machine-readable interfaces to facilitate third party integration and upgrades without having to come up with consensus-based standards.

“From a MOSA perspective, I would say that there was some inherent conflict in the current language between consensus-based standards, and incremental standards based on APIs [application program interfaces] and the way the commercial sector does things. So we kind of come down on one side of that to some degree, and clarify the statutory language to be consistent,” the official said.

On the test and evaluation side, the NDAA will propose “something of an alternative T&E approach” for software, but “not a major revolution” for the entire test and evaluation ecosystem, the congressional official said.

The bill also carries over other policy changes from the FORGED Act, including the repeal of certain acquisition rules thought to be overly burdensome or outdated and rolling back the powers of the Joint Requirements Oversight Council, to be focused on evaluating trends and providing recommendations on military solutions.

Senate, House Both Pushing Reforms

Not all of the acquisition reform changes proposed in SASC’s version the bill may make it to the final form of the legislation. The House Armed Services Committee has also made acquisition reform the focus of its version of the NDAA, drafting competing legislation known as the SPEED Act meant to hasten the weapons buying process.

The SPEED Act centers on overhauling the requirements generation process, with changes made to the structure of the Joint Requirements Oversight Council that are like what is contained in SASC’s acquisition reform plan. It also includes language meant to give program managers additional budget flexibility — changes that, while different than SASC’s tactic of moving to a portfolio management strategy, are similarly intended to free Pentagon acquisition personnel from bureaucratic chokepoints.

HASC and SASC will have to settle on a singular acquisition reform vision during the conference process, when the committees work together on a final form of the bill.

“Some of the things that you don’t see out of [HASC] is mostly the nontraditional and commercial contracting stuff,” but overall the bills are “very aligned,” the official said. “I think that they are introducing a lot of good ideas and thoughts, and we’ll be able to have those conversations.”

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Valerie Insinna

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://breakingdefense.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.