This post The Gospel According to Compound Interest appeared first on Daily Reckoning.

The sin that dare not speak its name now goes by a fancier title: financial innovation.

Yes, I’m talking about usury—that nasty little habit of charging interest on loans, once banned by Church councils and now blessed by every central bank in Christendom.

But before it became the spiritual backbone of capitalism, usury was considered a crime, not just against man, but against God.

In the Old World, the prophets and philosophers saw usury for what it was: legalized predation. Moses, Plato, Aristotle, and Muhammad all denounced it. It wasn’t just that excessive interest was a problem. Any interest was viewed as theft cloaked in civility. You don’t charge your brother to lend him a hand, do you? Why then should you charge him for a bag of wheat or a few coins?

The Bible minced no words: “You shall not lend money, or grain, or anything else at all, to your brother at interest.” (Deuteronomy 23:19). It had a different opinion toward foreigners. Then, the early Church picked up where the Torah left off.

Aquinas vs. The Moneylenders

Enter Thomas Aquinas, the Doctor Angelicus himself.

To Aquinas, usury wasn’t just a violation of charity—it was a metaphysical offense. Money, he said, was sterile. It couldn’t “breed.” To charge interest was to pretend that money could make more money by itself, without labor, land, or risk. That wasn’t an investment—it was alchemy.

Aquinas argued that usury violated natural law and, therefore, divine law. His was the gold standard of scholastic thought: clear, logical, and morally uncompromising. If you lent money, you got your principal back. That’s it. Any extra was theft.

So, where did we go wrong?

From Sin to Regulation—Henry VIII’s Great Pivot

Well, like most things in history, the trouble began when kings ran out of cash.

By the time Henry VIII sat his bloated posterior on the English throne, trade and empire were on the rise. The Tudors needed capital, and the Church’s hard line on usury was, shall we say, inconvenient.

In 1545, Henry passed the Act Against Usury, which capped interest at 10% annually. It was a compromise, not a moral victory. But it opened the floodgates. By 1571, even Parliament admitted the obvious: banning usury was futile. Might as well regulate it instead.

By then, usury had become a necessary evil, like Congress or reality television. And over time, the “evil” part quietly disappeared from polite conversation.

From Luther to Wall Street

To his credit, Martin Luther continued to rail against usury. However, the Protestant world eventually adopted it, especially after Calvinists began financing colonial ventures and New World plantations.

Commerce won. Conscience lost.

Today, usury survives in polite society under softer terms—”interest,” “APR,” “discount rate.” But make no mistake: the structure remains. Borrowers still get fleeced. And lenders still sing hymns to the invisible hand while they auction off your future.

The Cost of Civilized Extortion

Critics, both secular and sacred, have long warned of the economic decay caused by usury.

High interest rates trap people in debt cycles. They inflate prices, raise production costs, and fuel speculation over investment. Usury concentrates wealth in fewer hands, weakens institutions through defaults, and threatens systemic collapse—see the 2008 financial crisis.

Meanwhile, defenders argue that interest is the grease in capitalism’s gears. True enough—when rates are reasonable, credit funds innovation, entrepreneurship, and growth. But where’s the line between productive lending and parasitic skimming?

We rarely ask. We’re too busy refinancing.

The Evolution of Sin

Here’s the kicker: the Church never actually changed its theology. The sin of usury remains a sin, technically. It’s just been ignored into oblivion. And the economic theologians of our age—those central bankers and investment banks—prefer their morality in spreadsheets and footnotes.

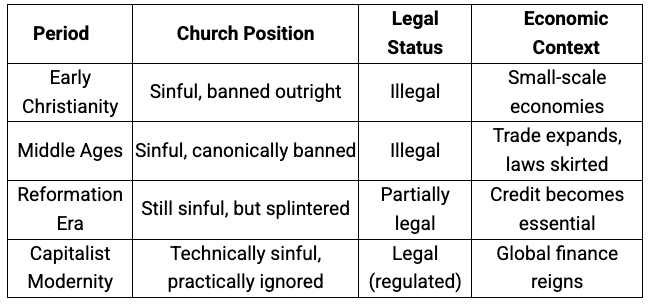

Here’s a cheat sheet for how it all played out:

Wrap Up

So, what is usury today? Is it a historical curiosity? A theological relic? Or is it the very bloodstream of our economic system?

If you ask Aquinas, he’d probably say we’ve dressed up theft in high finance and called it virtue.

If you ask the World Bank, they’ll point to credit-fueled GDP growth and smile.

If you ask a payday borrower paying 400% APR, they’ll give you a more honest answer.

In the end, usury hasn’t disappeared. It just changed uniforms.

And it still does what it’s always done: Make the rich richer, the poor poorer, and all of us complicit in a system we once called sin.

The post The Gospel According to Compound Interest appeared first on Daily Reckoning.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Sean Ring

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://dailyreckoning.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.