Albert Votaw—for whom I am named—was born in 1925 in Media, Pennsylvania, the first son of my great-grandmother, who had immigrated from Russia, and my great-grandfather, Ernest, whose Pennsylvania Quaker family had been in the United States since the late 1600s. From his upbringing he inherited a rock-ribbed Quaker pacifism, which led him to become a conscientious objector as a young man during World War II. His service to our country was to be a medical test subject rather than carrying arms against his religious beliefs.

After the war, Albert began a career in international aid. This was a heady period for America and our citizens abroad; our expats were helping to rebuild war-ravaged Europe and build what was then known as the developing world. With the Marshall Plan he set off to post-war France, and it was there that he met my grandmother, Estera Votaw, an exotic and charming young Hungarian who had survived the Holocaust and was now studying at the Sorbonne. Despite her experiences losing her parents and much of her extended family to the Nazis, Eszti had an irrepressible spark and a cosmopolitan flair. They married in Chicago in 1953.

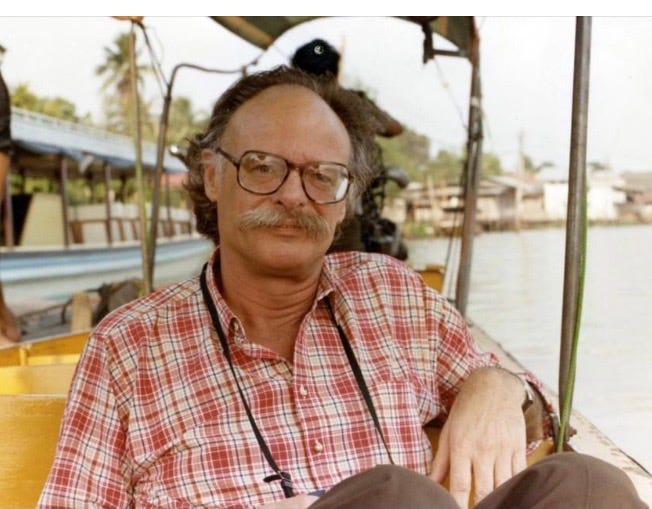

Albert and Eszti would go on to have four daughters—my mother their second—but that did not stop them from adventuring. In 1966, Albert was posted to the Ivory Coast as a United States Agency for International Development (USAID) official, where my grandparents spent nearly 15 years. Then it was off to Tunisia, back to Washington, D.C., and then to Bangkok in 1981. My grandparents were an upbeat and flamboyant couple, collecting West African art, shuttling their daughters around Europe for summer vacations, and returning to the States to visit relatives with many stories to tell. Everywhere the couple went, they created wide circles of expat and international friends, hosting parties, and venturing far afield from the path of most Americans, in an era before world travel became the norm for a certain class of people.

In the spring of 1983, the U.S. government transferred Albert to Lebanon, where he was the head of the housing office for USAID.

Two weeks after he arrived, on April 18, 1983, Iranian-backed Hezbollah terrorists drove a van packed with 2,000 pounds of explosives into the U.S. embassy in downtown Beirut. They killed 17 Americans and nearly 40 Lebanese, maiming over a hundred more people. The attack shattered the glass of buildings nearly a mile away—and tore a hole in my family tree.

My grandmother Eszti, whose parents were murdered by Hitler and her husband by Iran, had not even left their previous posting in Bangkok when she received the news of the Beirut embassy bombing. My parents, busy young newlyweds, were left to navigate life in the wake of the unimaginable phone call from across the world. Other members of the family were blown off course by the killing, some permanently.

The attack on the embassy, and the subsequent bombing in October of that year of the U.S. Marine Barracks in Beirut, in which more than 241 U.S. military personnel were killed, were, in retrospect, the dawning of the era of international terrorism.

But back then, Americans had not yet absorbed the reality of such spectacular and seemingly random violence. For my family, the experience was not just tragic; it was an isolating experience. Saying that your father had been killed in a terrorist attack was like saying he had been taken by marauding Visigoths. It was completely foreign.

Most people my age won’t remember the simultaneous Iranian-backed attacks targeting U.S. embassies in East Africa—Nairobi and Dar es Salaam—even though they killed hundreds. But I remember August 7, 1998, vividly. I walked downstairs at the age of 7 to find my mother sobbing in front of the television, reliving her own tragedy.

It was not till September 2001 that most Americans came to understand what it meant to have blue skies turn to fire—and to have your loved ones leave for work and never come home.

When my older twin siblings were born in 1987, my grandfather’s death was still too raw for my mother to even say the name “Albert” out loud. But by the time I arrived in 1991, her third and last child, my mother gave me that name—her greatest gift to me after my own life.

Nobody was ever the same; and as my mother recently told me, there is no “closure.” Closure is something for people who are not directly involved in a tragedy, the invisible boundary they set for themselves beyond which they are allowed to move on. For my mother, and thousands like her whose lives have been seared by terrorism, there is no ending—just a permanent ache that waxes and wanes with the tide of life.

But this season there is a new feeling that she, a pacifist of Quaker lineage, has experienced: justice. The news that Fuad Shukr, accused by the U.S. of being one of the masterminds of the 1983 U.S. Embassy bombing, was killed by the Israel Defense Forces in Beirut last summer gave her a sense, at last, that some justice had finally been served.

My grandfather was not an invading conqueror. He was a civilian employee of the U.S. government whose desire was to help build up other countries. He was murdered in 1983 by a regime that considers anyone they don’t like an enemy to be enslaved, tortured, or killed. This is not a regime that should ever be trusted with nuclear weapons, and our country’s involvement this weekend in preventing that from happening is justified. In any conflict, if there is one side deliberately targeting civilians—as Iran has done to its own people and to countless Americans since the ayatollahs came to power in 1979—we should know that this is the side to oppose.

My late grandfather has 21 living descendants across three continents, with another set to arrive in the coming weeks. We are living lives and doing things I hope he would be proud of. But most importantly: We live.

Historians might not remember Albert Votaw’s name; those who murdered him likely don’t either. But we do. And some of us are blessed enough to be called Albert.

Albert Eisenberg is a political entrepreneur based between Charleston, South Carolina, and Pennsylvania. Follow him on X @Albydelphia.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Albert Eisenberg

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://bariweiss.substack.com feed and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.