Did the CDC Mislead Its Advisers on the RSV Antibody for Babies?

by Maryanne Demasi at Brownstone Institute

In June 2025, the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) vaccine advisory panel met for the first time since being overhauled by Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.

Kennedy had promised that his new appointees would demand full transparency and scrutinise the evidence before making recommendations.

He charged the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) with ending what he described as the “rubber stamp” culture of the old guard.

One of its first major votes was whether to endorse Merck’s new RSV monoclonal antibody for babies, nearly identical to Sanofi’s version approved in 2023.

The CDC assured the committee there were “no safety concerns.”

That assurance helped the vote pass 5–2, and newly appointed CDC Director Susan Monarez soon signed off on the recommendation, paving the way for a nationwide rollout this autumn and winter in the US.

But further analysis suggests the CDC’s presentation may have buried evidence of harm—particularly neurological risks like seizures—raising doubts over whether ACIP members had the full picture before casting their votes.

Early Warnings in the Trials

Professor Retsef Levi, who cast one of the two dissenting votes, noticed a troubling pattern across four major clinical trials— Sanofi’s MEDLEY, MELODY, HARMONIE, and Merck’s CLEVER.

In each, there was a consistent imbalance in “nervous system” serious adverse events, most often including seizures, in the treatment groups compared to controls.

“Should we not be concerned about these potential safety signals?” Levi asked during the meeting.

Merck’s Dr. Anushua Sinha downplayed the concerns, saying there had been “extensive analysis of the events” and that Merck’s investigators had deemed that none of the nervous system harms were related to its product.

In short, ACIP was asked to take Merck’s word for it.

Levi acknowledged the numbers in the clinical trials were small and indicated that his decision would hinge on the post-marketing surveillance data.

The Post-Marketing Data That Was Shown

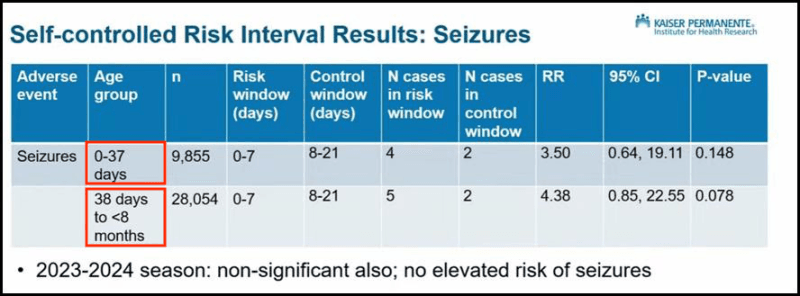

That post-marketing data came from the CDC’s Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) system, tracking safety reports for nirsevimab, Sanofi’s RSV monoclonal antibody already on the market and nearly identical to clesrovimab, the drug under review.

The presentation was delivered by Matthew Daley, a paediatrician at Kaiser Permanente Colorado—part of an organisation that has received funding from Sanofi, the manufacturer of nirsevimab.

When seizure outcomes—Levi’s primary concern—appeared on screen, the slide stayed up for barely a minute.

The results were split into two groups based on the age when babies received the injection (red box in graphic):

- Babies aged 0 to 37 days were 3.5 times more likely to have a seizure after injection but this was not statistically significant.

- Babies aged 38 days to under 8 months were 4.38 times more likely, but this was also not statistically significant.

Daley concluded that the CDC’s data showed “no significant increased risk.”

The Post-Marketing Analysis That Was NOT Shown

What Daley did not present is crucial.

When the two age groups are combined and analysed using a meta-analysis, babies were nearly four times more likely to have a seizure shortly after the injection (3.93, 95% CI 1.21-12.79).

This result is statistically significant (p=0.02), making it unlikely to be a chance finding—a fact confirmed by three independent experts.

By splitting the cases into two groups, the signal of harm effectively vanished. ACIP members were never shown the pooled result.

The choice to divide the data at 37 days is puzzling.

There is no clear clinical or biological reason for that cutoff — it looks entirely arbitrary, fueling suspicion it was chosen after the fact, once the results were known.

Other Study Design Limitations

The way the CDC set up its analysis introduced another flaw.

It used a self-controlled risk interval design, counting seizures only in the first week after injection (days 0–7) and treating the following two weeks (days 8–21) as a “control” period.

This creates a blind spot.

Let’s say a seizure occurred on day 8. It would be counted as part of the control period — implying it was unrelated to the injection, even though it may well have been caused by it.

It is customary in these situations to vary the risk window. By cutting off the window so early, genuine adverse reactions could be misclassified as background events—making the product appear safer than it really is.

Could the Vote Have Gone Differently if ACIP Knew?

Had ACIP members seen both the trial data — which showed a consistent imbalance in nervous system harms — alongside the pooled seizure data demonstrating a statistically significant risk, they might have recognised a clear safety signal and voted differently.

Given the narrow 5–2 margin, persuading only two more members could have blocked the recommendation.

Silence from the CDC

A media relations officer at Kaiser Permanente Colorado said Dr Matthew Daley “won’t be available” for comment.

The CDC also remained tight-lipped and did not answer questions about why it split the seizure data or why ACIP wasn’t shown the combined result.

I approached the panel members individually for comment, but instead received a response from Andrew Nixon, Director of Communications at HHS—the department that handpicked the ACIP panel.

“ACIP members receive available safety and effectiveness data to guide their decisions, and the committee’s process is grounded in transparency and scientific rigor,” Nixon said. “ACIP will continue to monitor RSV monoclonal antibodies closely and address new safety concerns that may arise.”

But sources close to the process told me that some panel members, since being alerted to the omitted analysis, are troubled and disappointed that they were not shown the full picture before casting their votes.

This is not a minor oversight.

The entire purpose of an independent advisory panel like ACIP is to weigh benefits against harms with full access to the evidence. By withholding combined, statistically significant data, the CDC denied its advisers that chance.

At Stake for Newborns

The seizure risk is likely to be a class effect, meaning it could apply to all RSV monoclonal antibodies now approved, potentially affecting millions of newborns worldwide.

If the CDC presents safety data in a way that downplays clear signals of harm, the promise of a “reformed” advisory process collapses before it even begins.

This episode is the first real test of Kennedy’s overhaul of ACIP because if the CDC can still bury inconvenient data, has anything really changed?

Republished from the author’s Substack

Did the CDC Mislead Its Advisers on the RSV Antibody for Babies?

by Maryanne Demasi at Brownstone Institute – Daily Economics, Policy, Public Health, Society

Author: Maryanne Demasi

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://brownstone.org and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.