I was listening to The Daily yesterday (California Strikes Back at Texas’ Power Grab), which is about the redistricting counter-moves by California.

In the middle of the conversation, the host, Rachel Adams, posed the following to her guest, reporter Laurel Rosenhall. It hits a deep frustration I have with the way Americans frequently talk about politics and elections. It also hit a problem that I have with contemporary journalism.

Rachel Abrams

I also wonder if this focus on redrawing maps takes away from the party’s basically just doing the work of convincing people that they’re the right ones to lead the country, that they are the ones with the better policies. What about just, I don’t know, old-fashioned persuasion to win elections?

Laurel Rosenhall

Yeah. It’s a really good question. And I think it’s something that the Democratic Party is going to have to confront in this battle. You’re going to hear people saying, is this really speaking to what voters care about, drawing district lines? How is that addressing their needs?

Let me get the journalism issue out of the way first. While I will allow that asking, “[Why not use] old-fashioned persuasion to win elections?” is a legitimate question, but I think that the framing here that focuses on the Democrats, rather than on US politics writ large, is a huge problem and an ongoing problem given the context. Sure, the podcast is focused on California, but again, the context is Trump asking Texas for more seats and Texas Republicans blatantly saying, “This plan is straightforward: improve Republican political performance.”

While I suspect a lot of listeners to The Daily are likely already concerned about Trump’s authoritarian behavior, it needs to be highlighted in a story like this. The administration is behaving outside the norms of American politics, and having more seats in the House will further empower that behavior. That’s the context, and it is a damned important one.

Setting that aside, the core problem is a persistent mythology that is so ingrained in American culture, which is the notion that we fundamentally have competitive elections and persuasion can save the day (or messaging, or popularism, etc, ad infinitum). If Democrats would just compete better, that is all that is needed.

Not understand, and please pay attention to the following: I am not saying Democrats are perfect. Yes, there is always room for improvement. Better candidates, better campaigns, better messaging, better policy, better McBetter bettering would be better. Better is always better.

Moreover, and please also pay attention to this, I am not saying the Democrats are my ideal political party and that I am all in on the leaders of the party and the way they campaign and govern.

All of this is more about the authoritarian turn of Trumpism and the flaws of our constitutional order far, far, far more than it is whatever real defenses the Democrats have.*

The problem persists that we all only have two choices of consequence, and at this present moment, the Republicans appear to be all-in on White nationalism, and are cool with authoritarian, fear-based, us-versus-them, militarized governance (all of those links are from stories posted just this week!). So the only alternative is the Democratic Party.

But, beyond the problem of journalists still trying to pretend like things are normal, or their allergies to being a bit more straightforward about what is going on, there is this deep belief that our system is mostly competitive.

It simply isn’t and hasn’t been.

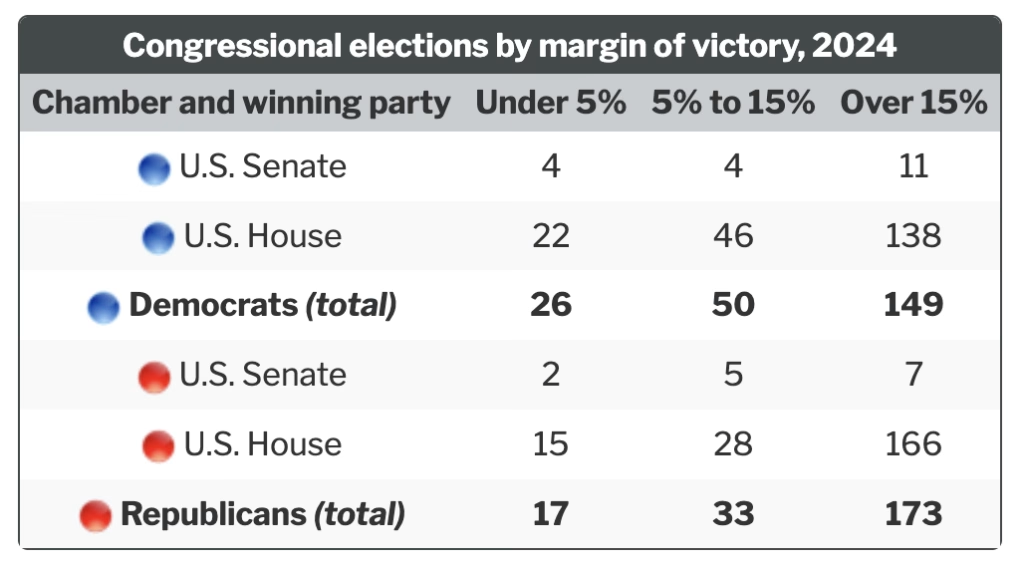

Look at the 2024 races for Congress from Ballotpedia. Only 37 House seats were competitive enough to have been won by less than five percentage points. That is 8.5%. The vast majority of seats (322 out of 435, or 74% of seats) had margins of victory over 15%.

Part of why, at this point, I am reluctantly in favor of Democrats playing power politics with redistricting is that it isn’t like the system isn’t already broken in many ways.

By way of illustration, I live in Alabama’s second congressional district. In 2022, that district went 69.1%-29.2% for Republican Barry Moore. In 2024, it went 54.6%-45.4% for Democrat Shomari Figures.

This was, of course, because of improved messaging by the Democratic Party and the persuasive arguments that they deployed to convince voters to choose differently. For this reason, the state’s ratio of Rs to Ds went from 6:1 to 5:2.

Or, as savvy readers realize, the preceding paragraph drips with sarcasm, and the real reason there was a different outcome is because the federal courts forced Alabama to redraw the districts because of the Voting Rights Act.

In the abstract, I agree that Democrats should work to compete better, but we, as Americans, have to come to grips with four sets of facts.

One, there is ample evidence and a vast and rigorous literature that shows that the basic institutional structures of any democratic system, including the basic electoral rules (how votes become offices), substantially shape the basic parameters of the party system. Some structures promote many parties, others incentivize fewer parties. To boil all of it down to this: we have a two-party system, not because it is “natural” or somehow inherent to US politics. We have two parties because of our governing institutions. As with all of these four points, there is more to it than this paragraph outlines, but in basic terms, there are features of our political institutions that may not dictate two parties specifically, but that definitely constrict the likelihood of a multi-party system.

Simply put, if we had more parties, some of the problems we are seeing would be vastly diminished and some of the worst impulses of national politics would likely be contained rather than controlling the federal government.

Two, human beings tend to be less persuadable than we like to think, which undercuts the “Why don’t Democrats just be better communicators?” argument. There is also a vast and rigorous literature on this topic. But it isn’t hard to see that things like views on the state of the economy or of Russia are clearly dependent not on the party adopting the views of its voters (which is the core of the persuasion argument) but, instead, the voters adopting the views of their party. See also, tariffs or vaccination rates.**

But another way: partisan identification as measured by voting is less fluid than are mass public opinions.

A model that assumes that voters choose their partisan allegiance because they first have a set of opinions and then choose the party that most fits those views is simply wrong in terms of mass behavior. It is far more likely that people’s partisan identifications are shaped by broader sociological factors, such as the partisanship of their parents, their educational background, their ethnicities, and so forth. And from that identity flows political and policy opinions.

This is not to say that some people don’t or can’t make choices and change their party allegiances based on specific views. But it is to say that that is not how most people behave.

Party ID is far more like allegiance to team sports (i.e., brought on by environmental factors like where you live and who your parents root for) than some rational calculation about public policy outcomes.

So, just one plus two means that in a strict two-party system that is highly polarized and where partisan identification influences opinion more than opinion influences partisan identification, and you get a situation wherein calling for persuasion as a solution to one party’s authoritarian behavior is a hopelessly naive suggestion.

But, it is is worse than that due to two other factors.

Third, US elections are not especially competitive, as noted above for the US House. But they are not especially competitive for most Senate seats. This is also true for a lot of state legislatures. Whatever competition there is is at the primary level, not the general election level. And while there is some level of national competitiveness for the presidency, on a state-by-state basis (which is how we elect the president) there is limited competitiveness, and presidential races become focused on a handful of states, which is not a democractically desirable outcome, as it focuses the campaigns more on those states than it does on building a true national coaltion.

Fourth, and to make the competition issue even worse, is that our constitutional system favors numerical minorities over numerical majorities. While the House is ostensibly linked to population, the chamber is too small, and it is possible, for a variety of reasons, for a party to collectively lose the national majority of the vote and still win a majority of the seats. This is a minor issue compared to the Senate, as we are in a cycle wherein the odds that a minority of citizens control a majority of seats are extremely high. And, as we know, the president can be elected with a minority of the popular vote. And, as happened in the first Trump term, a minority-supported president and minority-supported Senate can substantially reshape the Supreme Court and federal judiciary for a generation if the institutional cards fall the right way.

So, we have the following.

- Voters have only two viable choices.

- Partisan IDs lead to policy preferences, not the other way around.

- Most general elections for legislative seats in particular are not competitive.

- Structures that empower the minority over the majority.

As such, and not to sound too harsh, but spare me the notion that the politics of persuasion are going to solve our broader democratic deficit.

As a minimum, Americans need to jettison the notion that our system is open and highly competitive, but rather that is actually far more determinative than we like to think.

Two key results of all of this are as follows

- Primaries become one of the few places where there is potentially real competition.*** And therefore, members of Congress really only represent the narrow selectorate within their broader constituencies. They have no incentive to serve their states or districts, but instead are only worried about re-nomination.

- Since there is real competition for the presidency, that is where the parties and various elites focus their attention. And it is why we have seen long-term concentration of power in the executive and why Trump is able to behave as he is with executive orders, bullying law firms and universities, DOGE, militarizing DC, and the like. And it is why I fear we have fully shifted into an era of some version of delegative democracy, wherein every four years we elect a president who then does as much as they can get away with, norms and laws be damned.****

So, while we are still governed by people who are elected, and hence still have democracy in that sense, it is a far more limited democracy than most of want to admit to ourselves.

If most House, Senate, and state-level Electoral Votes are largely predetermined and if the only competitive elections are in primaries, and the only major institution open to any kind of real (yet very flawed) compeittion is the presidency, then the degree to which our government is truly responsive to the public is quite limited, is it not?

*Goodness knows that if I were conjuring the best opponent to Trumpism, it wouldn’t be the contemporary Democrats. And even from a policy-preference POV, the Dems are not my ideal. But you go to war with the army you have, something, somethiung.

**Attitudes on vaccinations are a great, albeit sad and frustrating, example. Anti-vax sentiment used to be a fringe view, often on what might be described as the hippy left (although also in some of the extreme religious right as well). But less than 10 years ago, it was a largely nonpartisan, almost nonpolitical issue. Vaccinating one’s kids was seen as right and proper, and no one thought getting a flu shot was an act of partisanship. But the Trump administration’s response to COVID (so ironic, given the success of Project Warp Speed) and subsequent moves like elevating RFK, Jr., have made vaccines partisan. Even for people who not that long ago would never have seen the topic as political.

***BTW, I would note by way of illustration the way that GOP members of Congress feared the notion that Elon Musk might fund primary challengers (see, e.g., Senator Ernst and the Hegseth vote). That is what it looks like when a politician fears competition and what a responsive member of the legislature should look like. But the problem was that Ernst didn’t fear the broader electorate she represents, but rather only feared primary voters. This, in turn, affects behavior in a way that serves extremes within her party.

****More on that topic soon. Also: Linz was right.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Steven L. Taylor

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://www.outsidethebeltway.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.