Beware Universal Mental Health Screening

by Cooper Davis at Brownstone Institute

How would your child score on a common mental health screening?

A mental health professional might view the results and conclude that your child has a mental health problem…that needs to be psychiatrically diagnosed and treated, even medicated.

Will this help your child thrive? Or will it reshape their identity in undesirable ways? Will you be comfortable with your child taking medications that alter their developing brains and could perturb their sexuality? When your child reaches adulthood, will they be able to withdraw from these drugs, or will they despair to find out that their body and brain have adapted to them, making this difficult or maybe even impossible?

For any parent with even minor reservations about our current medical and mental health system, these aren’t theoretical questions. A new public policy has just made them very salient.

Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker has signed a new law mandating universal mental health screenings for every child in public school. This includes healthy children with no signs of behavioral problems. Parents can theoretically opt out, but they’ll have to do so repeatedly, as the screenings will be given at least once a year from grades 3-12.

Media coverage has been laudatory, expounding on the importance of “getting kids the help and support they deserve.” But do you know what a mental health screen is and how it works? Before sounding the applause, parents need to understand what these screenings are, how they’re used, and what the potential outcomes of their use might be.

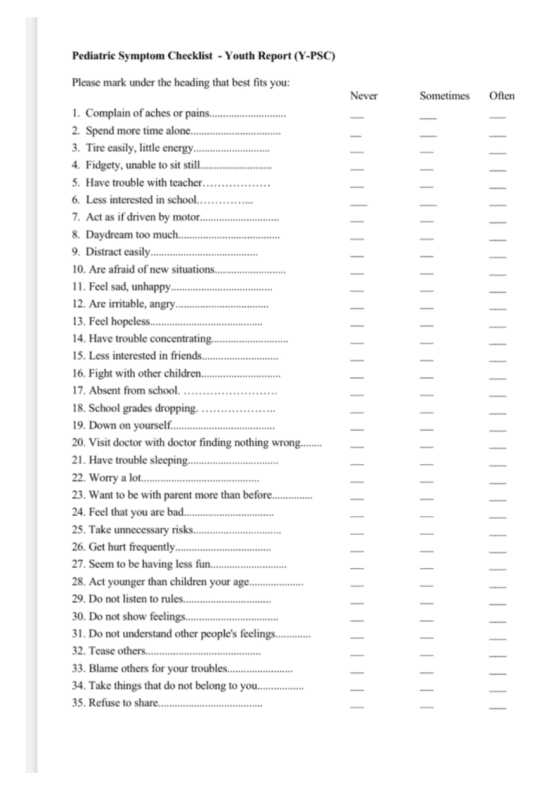

The new law does not specify how children will be screened, what questionnaires will be used, or what procedures will be followed when a child’s answers are seen as troubling. But to get a sense of the ground that self-report mental health questionnaires cover, you can screen your kids right now with a commonly used questionnaire:

While this is a self-assessment, the questions are the same whether you’re a parent or teacher filling this out on behalf of a child. Each of the 35 questions can be answered “never,” “sometimes,” or “often.” The scoring is simple:

- 0 = “never”

- 1 = “sometimes”

- 2 = “often”

If the total score is at or above 28, professionals will consider it likely that your child has a mental health problem. The law doesn’t define what happens next. Ideally, there would be a lengthy (and costly) multi-hour clinical assessment for each such child that views these results skeptically, and heavily considers normal developmental issues and transitory problems. In the real-world mental health system, it’s hard to imagine that actually happening.

Unfortunately, the bias of the current system is towards overmedicalization, overdiagnosis, and overtreatment. The implementation of universal screening is likely to worsen these problems.

In the past, some physicians gave annual chest X-rays to smokers. This was a form of universal screening in response to concerns about lung cancer. At first blush, this sounds reasonable. The problem? False-positive results. Studies showed that annual X-rays did not prevent mortality. They did cause anxiety in patients. And incidental findings were common, causing unnecessary biopsies, procedures, and interventions.

Current screening guidelines now target high-risk individuals. This is an example where the medical establishment carefully weighed the risks and benefits of universal screening and concluded that it was not in the interests of patients, and with a well-defined disease in mind, lung cancer.

Mental health diagnosis is not like cancer. It is a fuzzy, subjective enterprise. We don’t have blood tests or brain scans; we have flawed checklists and clinical judgment. And obviously, being improperly identified as having a mental disorder comes with a real cost for the child.

Screening every single child makes it inevitable that some healthy children will be thrust into the mental health pipeline. Even assuming that the questionnaires work reasonably well, a 15% false-positive rate is likely. Combine this false-positive rate with twice-a-year universal screening from grades 3-12, and your child will have 20 separate chances to be wrongly identified as having a mental health problem…at which point the government ostensibly gets involved in the mental health of your child.

It’s easy to imagine the catastrophic results. A child’s mental health screen inaccurately identifies a mental health problem; the busy therapist confirms a diagnosis; there’s eventually a referral to a psychiatrist, who prescribes psychotropic medication. Out of 20 screenings, this only has to happen once to alter your child’s life forever.

I (C.D.) know, because it happened to me.

I was caught up in a similar diagnostic dragnet in 1991, when my teacher read about Ritalin in Time magazine and began “identifying” students she believed might have the condition, which at the time was known as “ADD” (the “H”, for hyperactivity, came later). My parents chose not to medicate me, but did send me to a psychologist and a pediatric psychiatrist. From them, I learned that my constant chair-tipping, foot-tapping, wiggling, and inability to tolerate boredom — the very traits that drove me to act out in class and leave little space between impulse and action — weren’t just part of me, but symptoms of a medical condition. It was presented as both permanently part of my nature and “acceptable,” yet somehow also extrinsic to me and framed primarily as a “deficit.” (At that time, ADD was not as widely viewed as a full disability as it is today.)

At 17, when I was legally able to decide for myself — though I now view the “informed” part as questionable — I chose to begin drug treatment. Even without the drugs, however, the diagnosis had already shaped my sense of self: diminishing my agency, reinforcing a feeling of abnormality, and feeding the belief that my more organized, conscientious, and inconspicuous peers possessed something essential that I never would. You can hear a fuller account in The Atlantic’s Scripts podcast series (“The Mandala Effect,” Episode 2, on YouTube).

My experience is just one example of how a single screening can lock a child into a lifelong diagnostic identity — and once that process starts, there are few real off-ramps. Surely no one in favor of this law wants that scenario to come true for any child.

But with 1.4 million schoolchildren in Illinois, we’re talking about dealing with the results of up to 28 million separate mental health screenings in the decade after implementation. Will the mental health professionals dealing with this deluge approach the medicalization of your child’s supposed problems carefully, gingerly, sensitively? A 2004 study found that screening 1,000 children for ADHD using the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM criteria would result in 370 false positives. And it’s common for children to be prescribed psychotropic medication at their first consultation with their physician or psychiatrist.

A comprehensive, in-depth psychological assessment for each child might help reduce false positives — but it would also mean spending 3-6 hours assessing each child, which represents a high burden in terms of both time and money. School districts in Illinois already report that a lack of time, expertise, and financial resources presents challenges to implementing universal mental health screening. The law passed anyway.

It’s hard to argue that attempts to identify and measure human misery, suffering, and emotional pain are a bad thing, etc.—especially when the goal is “getting people the help they need.” It sounds right. But the kids who will be screened every year in Illinois? They have many kinds of problems: social, relational, environmental, academic, psychological, and physical problems. Children today have issues navigating a modern life dominated by endless screens, scrolling, and even more endless data.

And also, they have some problems that you’re supposed to have—problems that have been a critical part of growing up since the dawn of time.

Our culture is currently debating the medicalization of human problems, the credibility of medicine, the influence of the pharmaceutical industry, and the ethics of imposing medical authority as state policy. Covid lockdowns were a prime example of this, and, similar to universal mental health screening, they were imposed without consideration of the unintended consequences.

Mandatory Covid vaccinations also led many Americans to rethink the role of government in their bodily autonomy, and to consider how arbitrary social policy could be when it claimed to be for the greater good (e.g., insisting that those with immunity to Covid must still get vaccinated). For those who have grown skeptical of medical authority, universal mental health screening will likely be viewed as another overextension of the government into the lives (and minds) of their children. Children aged 12-17 can already receive psychotherapy in Illinois without parental consent; universal screening offers a new on-ramp to this process.

The new Illinois law seems almost tone deaf, out of step with the lessons learned from Covid. This critique is cultural, social, and ethical in nature. But universal mental health screening is supposedly based on science. The new Illinois law does not give details; it just authorizes universal screening as if it is an unmitigated good. The devil (and the science, or lack thereof) will be in these details – how the policy is implemented. Assuming that the rationale for universal screening is scientific, we present critically important questions that should be addressed as procedures are developed:

- What is the evidence that universal mental health screening improves real-world outcomes for children? Is there evidence that it could cause harm? The scientific rationale for the program needs to be stated clearly, citing compelling data, and explicitly addressing the measures taken to avoid harm.

- Given that Illinois has already implemented universal mental health screening in some school districts, what were the outcomes for the children? After testing positive for a mental health condition, how many were further assessed, and how much time was spent on each child? How many ended up in psychotherapy or on medication? Usually, a pilot program tests the effectiveness of an intervention, and it is only adopted on a wide scale if it is shown to be effective and not harmful – where is that data?

- How many children a year does Illinois expect to inaccurately identify as having a mental health problem (e.g., how many false positives)? How many children will make it from 3rd to 12th grade without ever screening positive? What measures will address the known issue of false-positive results in universal screening? Do Illinois public schools have the time, money, and expertise to carefully assess each child who screens positive for multiple hours to ensure that they do not overdiagnose and overtreat Illinois children? If universal screening results in a surge of children who ultimately end up on psychiatric medication, how will the public know? Implementing this program without addressing these issues ignores the potential harm of universal screening.

- How will Illinois taxpayers know if this program is a success? What metrics will be tracked? The easy out is to focus on the implementation of the program, and if a high proportion of children are screened, call it a success, never mind the details or outcomes. But using the screening of children as a measure of success for a universal screening program is tautology; data must be collected that demonstrates that the program helps children measurably and does not harm them.

There are good reasons to object to the new Illinois program based on general principles. If the issues above go unaddressed, or if sufficient resources are not provided to allow careful and precise identification of children in distress, it has the potential to be a disaster.

Beware Universal Mental Health Screening

by Cooper Davis at Brownstone Institute – Daily Economics, Policy, Public Health, Society

Author: Cooper Davis

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://brownstone.org and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.