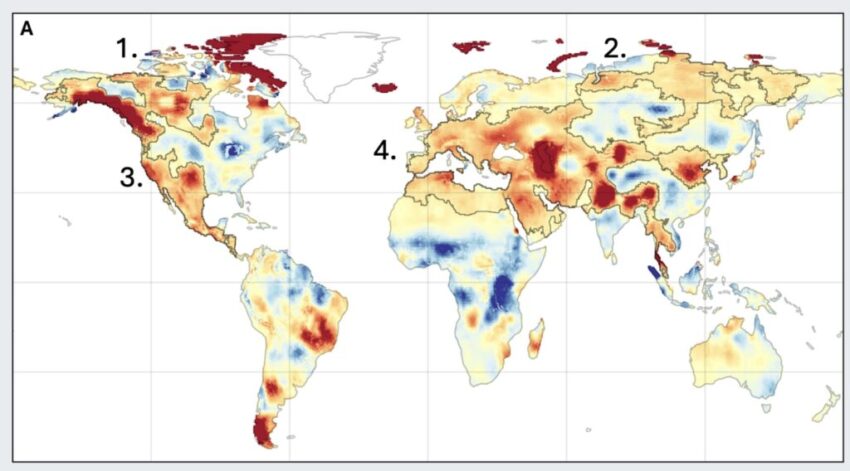

Mega-drying on the continents: 1 Northern Canada and Alaska; 2. Northern Russia; 3. Southwestern North America and Central America; 4. Middle East/North Africa/PanEurasia. (Map from “Unprecedented continental drying, shrinking freshwater availability, and increasing land contributions to sea level rise,” Science Advances, July, 2025.

Nevada, the driest state in the nation, is only getting drier as the region’s supply of groundwater quickly disappears.

The American Southwest – including Arizona, New Mexico, and portions of Nevada, Colorado, Utah and California – is linked to one of four continental-scale “mega-drying” regions worldwide that have undergone unprecedented rates of drying, according to a recent study in Science Advances.

The loss of freshwater from the regions is the result of two key factors: severe droughts and groundwater overuse.

Two decades of satellite observations revealed that as the dry areas of the world become drier and surface water in rivers and lakes declines, communities are becoming more reliant on groundwater, leading to rapid depletion of freshwater.

The lower Colorado River Basin – which supplies water for Nevada, Arizona, and California – has lost groundwater equivalent to Lake Mead’s full storage capacity in the last 20 years, or about 28 million acre-feet of water. An acre-foot of water is enough to supply roughly two urban households with indoor and outdoor water needs for a year.

“All the drying is happening in the Southwest. Three quarters of the country is getting a little bit wetter, but the southwestern quadrant of the country is getting a lot drier,” said Jay Fagmiglietti, the study co-author and Global Futures Professor at Arizona State’s School of Sustainability.

Even areas in the U.S. that are experiencing more precipitation are not keeping pace with the rate of rapid drying, leading to a net loss of freshwater, according to the study. The areas experiencing drying have increased, while the areas experiencing wetting have decreased.

Globally, drying land is expanding by about two times the size of California every year, according to the study.

The four “mega drying” regions globally are Alaska and Northern Canada, Northern Russia, Middle East/North Africa/PanEurasia, and Southwestern North America and Central America.

The research is especially noteworthy for Nevada, where about half the state’s counties rely on groundwater for more than 80% of their water supply, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. In 2015 Esmeralda, Eureka, Lincoln, Mineral and Nye counties received more than 95% of their water from groundwater.

Throughout several parts of Nevada, significantly more groundwater is extracted than is returned to aquifers each year, leading to declining water levels. About 20% of Nevada’s groundwater basins are currently over-pumped, according to the Nevada Division of Water Resources.

Despite the state’s dependence on groundwater, Nevada lacks detailed data on available groundwater. Water managers in Nevada currently rely on water budget estimates developed 50 to 70 years ago, raising major concerns about the accuracy of groundwater availability, according to the Nevada state agency.

The consequences of groundwater depletion in the Southwest include reduced irrigation water supply and threats to agricultural productivity, reduced capacity for climate adaptation, and damage to groundwater dependent ecosystems.

Most of Nevada’s rivers, streams, and lakes are groundwater dependent. Groundwater also plays a crucial role in supporting the state’s unique ecosystems. There are 242 wetland-dependent species recorded by Nevada Division of Natural Heritage – 143 of which can only be found in Nevada.

A growing awareness of ground water as a critical natural resource has raised several research questions: How much ground water do we have? Are we running out? Where are ground-water resources most stressed by human development?

Fagmiglietti said the study was conceived to answer some of those questions and prepare water managers for a drier future.

About 75% of the world’s population lives in the 101 countries that make up the four mega-drying regions, according to the study.

Researchers used satellites to measure changes in gravity to detect weight loss or gain in regions, indicating groundwater depletion or prolonged drought.

The research team said global drying is not slowing down. Their data indicates groundwater was lost three times faster over the last decade than in the prior one.

The loss of groundwater is also contributing more to global sea level rise than melting glaciers and ice caps, according to the study. Increased runoff from groundwater pumping and glacier melting contributes to the ocean’s water levels, exacerbating sea level rise.

“Drying continents themselves are now contributing, they’re the largest contributor to sea level rise, ahead of either the Greenland or the Antarctic ice sheet,” Fagmiglietti said.

“We pump groundwater for irrigation. And a lot of that, you know, doesn’t make it back into the ground. It evaporates, or it runs off, and ultimately ends up in the ocean,” he said.

The study also points to a tipping point during the “mega El-Niño” years around 2014 to 2015 when equatorial waters in the Pacific were 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius above average. During that period climate extremes began to accelerate, leading to more groundwater usage to cover the lack of rainfall.

Fagmiglietti emphasized the critical importance of groundwater in drying regions and the need for better management and protection. Groundwater is often unprotected and unmonitored, Fagmiglietti said, making it at risk in many regions around the world. States need to recognize the importance of groundwater and enforce effective management policies.

“Communities that depend on groundwater entirely, again, need to understand that that groundwater is disappearing rapidly. They need to understand what their supply looks like and need to prioritize how they’re going to use it and try to sustain it,” he said.

Last week, federal officials announced they would continue water allocation cuts on the Colorado River for the fifth consecutive year following a persistent drought that has shrunken Lake Mead, the river’s largest reservoir. Persistent drought like the one impacting the reservoir will only put more pressure on groundwater, said Fagmiglietti.

“No one ever talks about the groundwater, especially when it comes to the Colorado River. Discussion is always about the reservoirs and the river itself, but really thinking holistically about how much water you have in the region is really, really important, and in particular with the increased stress that will happen on groundwater,” Fagmiglietti said.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Jeniffer Solis

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://www.nevadacurrent.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.