Historians who are susceptible to myths tend to view Charlemagne’s veneration in Central Europe as a continuous phenomenon. In fact, based on the Hun–Hungarian kinship, they would like to attribute the Hungarians’ pilgrimages to Charlemagne’s reliquary in Aachen to the Hungarians’ remorse over the 11,000 virgins slaughtered by Attila the Hun in Cologne. There is some truth in all this, as Charlemagne not only appeared in Hungary according to literary tradition, but also visited the country during his campaign against the Avars. Thus, Charlemagne’s figure is not entirely unfounded in connecting Hungary with the Crusades and the Holy Land. Charlemagne’s biographer Einhard identified the Avars and Huns in his description of the Franks’ 791 campaign in Pannonia. This identification had a rich afterlife, to the extent that the Frankish emperor was credited with introducing Christianity to Hungary. According to chronicler Antonio Bonfini (d. 1503), who was active in Hungary around 1500, Charlemagne personally marched into Buda. It is no coincidence that the Hungarian chancellor, Archbishop János Vitéz of Esztergom, mentioned Charlemagne alongside Godfrey of Bouillon as one of the greatest heroes of the Crusades in his speech defending Hungarian interests at the Imperial Diet in Frankfurt in 1454.

If Westerners had negative preconceptions about Hungarians, the events of the First Crusade in Hungary only reinforced them. In the Chanson d’Antioche and the Song of Roland, the Hungarians appear in the camp of the Muslim emir. This reflects both the lingering dishonourable image of the destructive Hungarian raids of the 10th century and the negative experiences of undisciplined Western crusaders who passed through the country in 1096.[1] Their passage, which led to serious armed conflicts, may have come as a surprise to the leaders of the newly Christianized kingdom, but it did not deter the Hungarians from supporting the peaceful pilgrims and crusaders, and the pilgrimage route remained open to them.

‘If Westerners had negative preconceptions about Hungarians, the events of the First Crusade in Hungary only reinforced them’

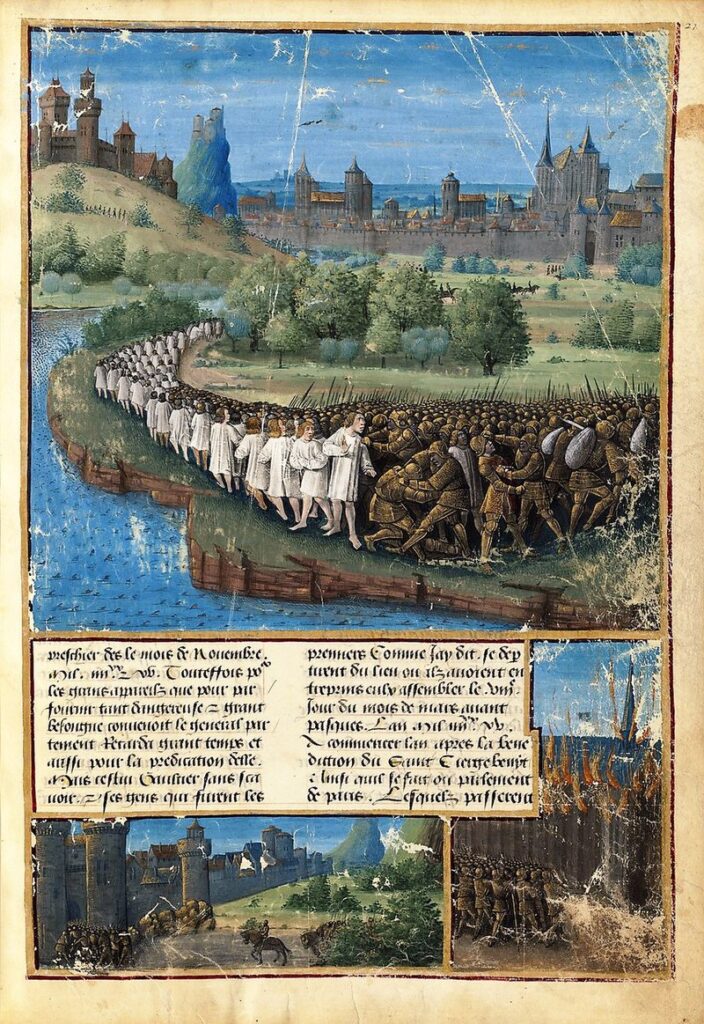

However, there were also positive experiences. According to chronicler William of Tyre (d. 1184), Godfrey of Bouillon’s passage through the Hungarian border in September 1096 was peaceful, thanks to an agreement between the Hungarian king and the Duke of Lower Lorraine. The prince’s brother, Baldwin, the first king of Jerusalem, and Raymond de Saint-Gilles, later Count of Tripoli, were members of the illustrious crusader army. According to a slightly later account by chronicler Gilo of Paris, Godfrey visited St Martin’s Mountain, then considered the birthplace of St Martin, today’s Pannonhalma Monastery, perhaps on 11 November, St Martin’s Day. There, King Coloman of Hungary (r. 1095–1106) solemnly welcomed him with a procession in the company of the bishops of the country.

‘As the agreed day arrived, this city shone in splendour, the rich Sabaria[2] from whence your holy native son Martin radiated throughout the world. The pious King [Coloman] arrived in this place with assembled bishops, his nobles, ordinary people and the holy clergy, who all gathered together carrying candles, crosses, gospels, holy relics and precious objects from churches to welcome them [ie Godfrey, Baldwin, and other nobles]. [Coloman] kissed them on arrival and led them to the cathedral, accompanied by joyful exclamations and the sound of hymns, aggrandizing their splendid and hospitable reception in a royal manner and confirming their treaty by the exchange of hostages.’[3]

Later, during the Second Crusade, the French army marched through Hungary in the summer of 1147 under the leadership of King Louis VII (r. 1137–1180). We can learn about the diplomatic gifts exchanged between the Hungarian and French kings from the description of Odo of Deuil, a chronicler accompanying the French king, who later became abbot of St Denis. King Louis became godfather to the firstborn son of the Hungarian king, the future King Stephen III (r. 1162–72), which the Hungarians reciprocated by providing the army with abundant supplies.

From the middle of the 14th century, the Ottoman advance in the Balkans shifted the front line between Christianity and Islam to European territory. By 1390 Ottoman incursions had reached the southern borders of Hungary, marking the beginning of the Hungarian Kingdom’s defensive wars, which were supported to varying degrees by international forces, including France and Burgundy. The 1396 Nicopolis (now Bulgaria) campaign was the largest crusade of the 14th century, organized by King of Hungary Sigismund of Luxembourg (r. 1387–1437). Sigismund realized the danger of the Ottoman threat early in his reign. As a member of a European dynasty, he recognized that only international cooperation could help, and he wanted to rely in particular on the French and Burgundian territories,[4] which were home to the most famous knights of the time. The knights who came from these regions had considerable combat experience, as they were regular participants in the crusades in Prussia and North Africa. Some of them had already been to Hungary before, such as Jean II le Maingre, also known as Boucicaut, Marshal of France in 1388, or Philipp of Artois, Count of Eu and Constable of France in 1394, who led a larger army. After Sigismund’s envoys won the support of the French court for a crusade in Paris in 1395, 250 men set out the following year, accompanied by Count Jean de Nevers.

There were perhaps a thousand people who arrived from here, among whom were Flemish people, citizens of Bruges, subjects of Artois and Picardy, as well as Englishmen. One of the most famous soldiers was undoubtedly Marshal Boucicaut, with his army of 70 men, whose memory was immortalized in his biography, Livre des fais.[5] He was rivalled in fame only by Enguerrand de Coucy, the son-in-law of the English king, who, together with John of Nevers, later Duke of Burgundy, led the main army in the battle and died in Turkish captivity in 1397.

In the battle that took place on 25 September 1396, the French formed the vanguard and launched the first attack. The Crusader army suffered a catastrophic defeat, which did not damage the reputation of the French participants. The knights who returned from captivity or were ransomed at great cost, such as Boucicaut, were hailed as heroes, and John of Nevers’ epithet ‘the Fearless’ or ‘sans peur’ is also explained by the memory of this campaign. The remembrance of the battle lived on as a mournful memory in Hungary, while in the French–Burgundian territories it remained a defining experience of knightly heroism for centuries, and was even mentioned at the liberation of Buda in 1686. Many medieval literary adaptations have survived, such as Antoine de La Sale’s (d. 1462) novel Histoire de Petit Jehan de Saintré from 1455.[6]

‘The last great crusade was the Varna campaign in 1444, which swept across the entire Balkans’

French–Burgundian relations and joint crusade plans remained alive even in the 1430s, as evidenced by the visits to Hungary by Ghillebert de Lannoy and Bertrandon de la Broquière, envoys of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy. The leaders of the orders of knights were traditionally French, such as the later Grand Master of the Hospitallers Philibert de Naillac, who placed his ship anchored on the Danube at the disposal of King Sigismund fleeing from battle.

The last great crusade was the Varna campaign in 1444, which swept across the entire Balkans and reached the shores of the Black Sea. There were no Frenchmen in the army led by King Vladislaus I of Hungary and John Hunyadi, but they were present at sea. Our source, the chronicle of Jean de Wavrin (d. 1474), describes the activities of the Burgundian fleet, which was led by his nephew, Waleran de Wavrin. With only four ships at their disposal, they were unable to prevent the Turkish army from crossing the Black Sea, but in the summer of 1445, they sailed up the Danube with eight ships to support John Hunyadi. Waleran met Hunyadi in person at Nicopolis, whom he refers to as ‘le chevalier blanc’ (‘the White Knight’). Together, they visited the battlefield of Nicopolis in 1396, and he also provides such vivid details as, for example, the fact that Hunyadi, large and tall, had to take off his armour to enter his ship’s cabin.[7]

At the beginning of the 16th century, soldiers were replaced by diplomats, such as Antoine de Rincon (d. 1541), a Spaniard who entered the service of King Francis I of France and had been travelling in the region since 1522, striving to promote the establishment of a French–Hungarian alliance. The Ottoman occupation of Hungary and the prolonged intensification of power struggles between France and the Habsburgs brought the era of the Eastern European Crusades to a close for a long time, although the French reappeared on the side of the Habsburgs in the battles against the Ottomans in Hungary in the 16th and 17th centuries.

[1] John France, Victory in the East. A Military History of the First Crusade, Cambridge, 1994, pp. 90–95.

[2] Sabaria is the name of the Benedictine monastery in Pannonhalma, as the monks here appropriated the Latin place name, which originally referred to Szombathely, and the associated cult of St Martin.

[3] C W Grocock, and J E Siberry (ed. and transl.), The Historia vie Hierosolimitane of Gilo of Paris and a second anonymous author, Oxford, 1997, p. 50.

[4] Schnerb (Bertrand), ‘Le contingent franco-bourguignon a la croisade de Nicopolis’, in Jacques Paviot and Martine Chauney-Bouillot (eds.), Nicopolis, 1396–1993, Annales de Bourgogne, Vol. 68, 1996, pp. 59–74; Sándor Csernus, ‘Récits, chroniques et voyages en Terre Sainte. XIIe–XVIe siècle’, in György Tverdota (ed.), Écrire le voyage, Paris, 1994, pp. 125–143.

[5] Norman Housley, ‘Le maréchal Boucicaut à Nicopolis’, in Id, Crusading and Warfare in Medieval and Renaissance Europe, Variorum Collected Studies Series, Aldershot, 2001.

[6] Antoine de La Sale, Jehan de Saintré, Paris, 1995; Levente Péter Hamvas, ‘A nikápolyi csata emléke egy francia lovagregényben’, Hadtörténelmi Közlemények, Vol. 125, 2012, pp. 1051–1064.

[7] Richard Vaughan, Philip the Good: The Apogee of Burgundy, New York, 1970, pp. 271–272.

Related articles:

The post The Era of Crusades — The Kingdom of Hungary and the French Army appeared first on Hungarian Conservative.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: László Veszprémy

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://www.hungarianconservative.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.