La Sagesse divine donnant des lois aux rois et aux législateurs (“Divine Wisdom Giving Laws to Kings and Legislators”), Jean Baptiste Mauzaisse, 1827.

Ricardo Duchesne, Greatness and Ruin: Self-Reflection and Universalism Within European Civilization, Antelope Hill Publishing, 2025, 655+xii pages, $29.89 paperback

Nationalists have often pointed out that the defense of European-descended people and the civilization we have created does not depend on any belief in their intrinsic superiority. Even the most primitive and backward peoples defend themselves and advance their group interests, and there is no reason we should be different.

Yet, once Europeans opened up the world during the age of discovery, it became obvious to many of them that their civilization was also superior to the other civilizations, notably in its comparative rationality and its long record of achievement and invention. From the days of the conquistadors until the early 20th century, most people of European descent would have regarded this as obvious. And contrary to a now-widespread perception, confidence in Western superiority never involved any small-minded desire to deny or downplay the genuine achievements of others. A self-confident people feels no need for such dishonesty.

Greek Miracle vs. Axial Age

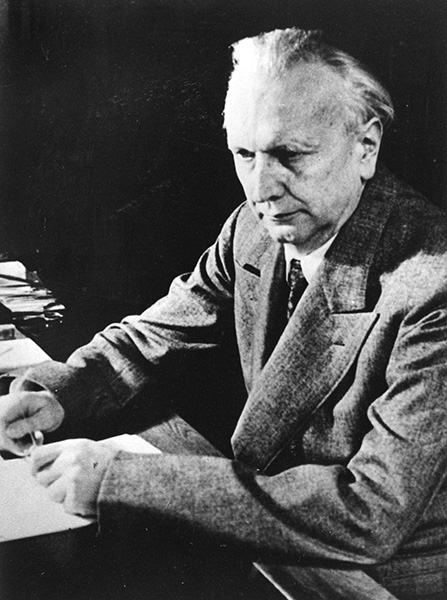

However, the disasters of the last century — especially the Second World War — struck a serious and perhaps fatal blow to such self-assurance. Whereas earlier generations had spoken of the rise of classical civilization as the “Greek Miracle,” viewing it as a unique and crucial step in human achievement, in 1949 the German philosopher Karl Jaspers (1883–1969) introduced the competing conception of the “Axial Age.”

German philosopher Karl Jaspers, 1946. (Credit Image: © Mondadori Portfolio via ZUMA Press)

In his telling, the Greek Miracle was just one of several comparable advances occurring around the middle centuries of the first millennium BC in Ancient Israel, India, China, and Persia, as well as in Greece. He wrote that the age of the Biblical prophets and Ezra’s reforms, of the Upanishads and Mahabharata, of Confucius and Lao Tzu, and of Zoroaster in Persia must no longer be overshadowed by an ethnocentric concentration on Greek rationalism and self-government.

Jaspers speculated that the Axial Age was a “manifestation of some profound common element, the one primal source of humanity.” He acknowledged that the apparently parallel developments of that age had been followed by civilizational divergence, and expressed the hope that divergence could be overcome as humanity learned to think of itself as a unity.

Ricardo Duchesne notes in his new book Greatness and Ruin that it was no accident such views found expression shortly after the Second World War by a philosopher from defeated Germany. Jaspers clearly saw National Socialism as an extreme example of cultural divergence, and like many men of the early postwar era, hoped to ensure future peace through international cooperation and understanding. It is the same thinking which gave rise to the exaggerated hopes for the United Nations, and something of it survives to this day in what is called “globalism.”

Jaspers is little read now, but his concept of an Axial Age of parallel development has enjoyed enormous success, developed further by talented scholars right up to the present. Treatments of the theme have also gradually shifted from Jaspers’ original universalist message to anti-Western hostility. Dr. Duchesne notes that one celebrated contemporary writer, Felipe Fernández-Armesto,

portrays Axial thinkers outside Greece as saintly, lofty and exalted sages, while ignoring most of the Greek thinkers and describing Plato as a “member of an Athenian gang of rich aristocrats” who idealized “harsh, reactionary, and illiberal” states, “militarism,” “regimentation,” “rigid class structure,” and “the selective breeding of superior human beings.”

The concept of an Axial Age has some merit: It is true that remarkable advances occurred independently in several civilizations between about 800 and 200 BC — in particular, Israel, India, and China. Egypt and Mesopotamia, however, were advanced civilizations that did not show any notable cultural flourishing during these “axial” centuries, and including Persia among those that did is at least dubious.

The more important question, however, is how plausibly any of these other episodes of cultural advance can be compared to the achievements of the Greeks from Homer to Archimedes. Dr. Duchesne examines China because a general consensus seems to have emerged, even among the most committed cultural egalitarians, that it can boast the most advanced civilization outside the West.

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development in cross-cultural perspective

Before we compare ancient Greek and Chinese thought, however, we must look at the ideas of Swiss child psychologist Jean Piaget (1896–1980), to which Dr. Duchesne appeals in making his case.

Piaget formulated the concept of four qualitatively distinct stages through which the human mind develops between infancy and adulthood, namely the sensorimotor (before age two), preoperational (from two until six or seven), concrete operational (until age twelve), and formal operational stages. As Dr. Duchesne observes, Piaget’s developmental scheme has stood the test of time far better than the work of many 20th century psychologists, although it has been supplemented and qualified, and although the boundaries between the four stages may be fuzzy and occur at different ages in different children.

Jean Piaget

Critics have also pointed out that Piaget formulated his ideas on the basis of his work with European children, leaving him open to the charge of “Eurocentrism.” However, some of Piaget’s early followers took an active interest in applying his insights cross-culturally, and found that not all the world’s peoples ever reach the formal operational stage of thinking that Piaget saw in European children after age 12. In plain English, many non-Western people think in a manner which Europeans would describe as juvenile.

In fact, Piaget’s followers came to the view that the most primitive hunter-gatherers and small agricultural village societies rarely get past even the second stage of mental development, the preoperational stage normally exited by Western children by age six or seven. Fetishism and animist religion are common at this level, with men who think nearly everything they see is caused by occult powers or spirits.

This does not mean such people are unable to produce anything worthy of admiration. Lucien Lévy-Bruhl, author of the classic study Primitive Thought (1923), even acknowledged that

there is no type of community, however inferior, in which some inventions, some process of industry or art, some manufacture may not be found to wonder at. . . . Primitive peoples may evince a wonderful memory, great powers of observation, and even be “acute reasoners” with regard to their survival skills.

Moreover, even at primitive stages, men may be reasonably high in what psychometricians call “genotypic IQ,” but their primitive cultures make it hard to develop intelligence to its phenotypic maximum. What Lévy-Bruhl does maintain is that “the primitive mind is devoid of abstract concepts, analytical reasoning, and logical consistency.”

All larger-scale agricultural societies that developed writing and cities — a level first attained by humanity in Ancient Sumer — reach at least the third, concrete operational stage. Men at this stage become less egocentric and start to work through things in their heads by using symbols. Yet they typically retain a weak grasp of causality: They cannot inquire into causal connections beyond noticing simple sensory relationships and do not understand that a single event can have multiple causes. They also conceive of their own thoughts as part of the things to which they refer, a phenomenon known to psychologists as “conceptual realism.” In Dr. Duchesne’s words, they

have no conception of an “I” in separation from the world around them. They are overwhelmed by multifarious forces within and without, feelings and instincts, noises and natural events, storms and hurricanes, the darkness of the forest, the vastness of the sea and sky, all intermingled with their dreams, fears, emotions, and appetites.

At this concrete operational level, people have a hard time recognizing contradictions between belief and experience, and even accept logical contradictions as part of the nature of things. When Walt Whitman wrote: “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself, I am large, I contain multitudes,” he was expressing this. Whatever its merits of contradiction as poetry, anyone who has reached Piaget’s fourth level of formal operational thinking cannot remain content with it, but must move on to Aristotle’s insight that a real (as opposed to merely verbal) contradiction is impossible. There do not seem to be any human societies that regularly attain Piaget’s formal operational stage apart from those influenced directly or indirectly by Ancient Greece.

Aristotle with a Bust of Homer, Rembrandt, 1653.

Obviously, this conclusion will not please Felipe Fernández-Armesto, and since people like him now largely control universities and major cultural institutions, the research program of applying Piaget’s developmental scheme cross-culturally has withered since about the 1970s. But that does not prove the unsoundness of doing so. A major aim of Dr. Duchesne’s Greatness and Ruin is to demonstrate the cross-cultural validity of Piaget’s scheme, particularly with reference to China. If this most advanced non-Western civilization can be shown never to have risen to the level of formal operational thinking, the same is likely to be true a fortiori of all other non-Western cultures.

China’s concrete operational civilization

Psychometricians have made abundantly clear that the Chinese are an exceptionally intelligent people, more intelligent on average than Europeans, and Classical Chinese civilization was very far from primitive. Sensible Westerners have always acknowledged this, from Marco Polo in the 13th century to Joseph Needham (1900–1995), who devoted 15 hefty volumes to cataloguing Chinese scientific and technical achievements. What remains more questionable is whether China’s cultural achievement has been comparable to that of the West, and that issue cannot be resolved by an insistence that it must have been — or else you’re a racist, whitey.

Western admirers of Chinese thought often describe it as “holistic” and “contextual,” in contrast to our supposedly narrow and dryly analytic style. This contrast points to a genuine difference, but Dr. Duchesne believes it can be best understood in terms of Piaget’s stages of mental development. Chinese thought never reached an understanding of the rational mind as distinct from the world of social roles and conventions. What Western Sinologists celebrate as the holistic and context-aware character of Chinese thinking results from its remaining embedded within its age-old inherited customs. Western thinkers from at least the age of Classical Greece transcended this stage by an awareness of their own rational faculty as something independent of convention and tradition. They were therefore able to view their own inherited culture objectively and critically. As Jacques Gernet, author of A History of Chinese Civilization (1972), has written, the Chinese never conceived “of a sovereign and independent faculty of reason.”

The mental gulf that separates China from the West is clearly revealed by their philosophical traditions. Chinese philosophers expressed themselves in short, disconnected, impressionistic aphorisms, often suggestive, but lacking rational argument. As Dr. Duchesne observes, their “statements lack demonstrative reasoning and clearly stated premises.” We may add that they also typically fail to define even such key terms as Dao or “Way.” This stands in the sharpest possible contrast to Socratic inquiry, which sought clear definitions of moral terms ordinary people are content to use vaguely.

The Chinese philosophical tradition is usually traced back to Confucius (551–479 BC), but as Dr. Duchesne notes:

Confucius never asked questions about the ultimate nature of reality. The Confucian term “all under heaven” does not refer to the universe, but is a term that denotes the geographical area associated with the political sovereignty of the emperor. [Confucianism is merely] a guide for proper moral behavior for the scholar gentry class of China’s despotic bureaucratic state.

China also developed a radically different tradition known as Daoism, characterized by some notably anticonventional aspects, a playful love of paradox, and a complete disregard for proper behavior for imperial bureaucrats. Yet few Chinese have ever felt any need to decide between Confucianism and Daoism, happily subscribing to both and applying them according to circumstance much in the spirit of Walt Whitman.

The teaching Confucius. Portrait by Wu Daozi, 685-758, Tang Dynasty.

Like Confucius and his disciples, Daoist writers such as Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu express themselves in aphorisms free of rational argument. They also share their Confucian rival’s lack of interest in conceptual clarity or careful definition. A key term of Daoist thinking, for example, is Xin, which can be translated as either heart or mind. Some Western Sinologists, in fact, render it “heart-mind.” Such a term, along with the lack of any that are more specific, bespeak a culture that has failed to grasp the distinction between rational thought and emotion. The Chinese language does not even possess accurate equivalents for such characteristically Western terms as mind and rationality.

These shortcomings are hardly unique to China or unknown in the West. Our civilization is filled with people unable to distinguish between thought and feeling, between logical inference and rational belief on the one hand, and their personal and subjective impulses and emotions on the other. In fact, all human beings begin life without that ability, and many less intelligent or less educated whites never manage to acquire it. So it is entirely plausible that the contrast between the rational analytic thinking of the West and China’s “holistic” and “context-aware” thinking can be best explained in terms of the contrast between those who have attained Piaget’s highest stage of formal operational thinking and those who haven’t.

As Dr. Duchesne writes:

Since ancient times, Westerners have been aware that each individual has a mind that is the seat of knowledge, which can be differentiated from bodily appetites, subjective emotions, and external objects. . . . It is not that the Chinese have a broader, more comprehensive outlook.

Rather, their ability to accept and incorporate “multiple perspectives” such as Confucianism and Daoism

are an expression of the multiple norms, circumstances, and bodily impressions surrounding them and unconsciously coalesced with their reasoning. Their minds have remained lodged in the world. The East Asian self is determined by the flux and fusion of inside and outside forces. Their minds have not been fully differentiated from the world around.

Western Sinologists sometimes speak as if the Chinese were fully aware of the distinction between their own “embedded” thinking and Western rationalism, consciously choosing the former as inherently superior. But this is not much more plausible than the notion that children in the 7-12 age range understand yet consciously reject formal operational thinking.

Chinese thinkers never articulated any concept of “the culturally embedded self.” Sinologists David Hall and Roger Ames, authors of Thinking from the Han (1998), celebrate the supposed superiority of socially embedded thinking by appealing to the ideas of the American Pragmatist philosopher George Herbert Mead, writing that Mead’s notion of the self “as a field of social relations constituting and constituted by the person is fundamental to our understanding of Chinese thought.” Their bibliography lists 260 sources of which only 36 are Chinese; two-thirds of the latter are ancient primary texts, leaving only 12 works of modern Chinese scholarship. At one point they even fall into unintentional comedy by offering the following as an example of China’s superior embedded and contextual style of thinking: “The Westerner encountering a strange plant or animal will ask ‘How may I classify this’ while the Chinese will ask ‘How may this be cooked?’”

Western vs. non-Western mathematics

Efforts to draw an equivalence between ancient Chinese aphorists and Greek philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle have parallels in today’s “multicultural mathematics” movement. If supporters limited themselves to noting that non-Westerners such as the Ancient Egyptians and Babylonians, the Chinese, Indians, and Islamic peoples made independent advances in mathematics, they would be right. But they go much farther.

George Gheverghese Joseph is an Indian-born historian of mathematics and the author of The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics (1991), the central academic text of the multicultural math movement. Dr. Duchesne acknowledges that it is “a solid book in its effort to bring out the best in nonwestern mathematics.” Less defensible is the author’s claim that European scholars have distorted and devalued the contributions of non-Europeans, especially “colonized peoples,” as part of an “ideology of racism and white superiority.”

Prof. Joseph cites only two works in support of his accusation: W. W. Rouse Ball’s A Short Account of the History of Mathematics (1888, with subsequent revisions) and Morris Kline’s Mathematics in Western Culture (1953). Yet neither work really provides such support. The first book considers the “Knowledge of the science of numbers possessed by Egyptians and Phoenicians” and “Greek indebtedness to Egyptians and Phoenicians.” It also has chapters on “The Mathematics of the Arabs” and on the “Introduction of Arabic Works into Europe 1150–1450.” Rouse Ball acknowledges that “the work of the Arabs . . . in arithmetic, algebra, and trigonometry was of a high order of excellence.”

As for Morris Kline’s book, it hardly seems fair to criticize it for ignoring non-Western contributions when its title is Mathematics in Western Culture. And Kline even followed this up in 1972 with a more comprehensive study called Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modern Times. This book, which Dr. Duchesne describes as “perhaps the most authoritative historical study published so far,” does devote attention to non-Western mathematics: It opens with chapters on the Mesopotamians and Egyptians, and includes another on “the Hindus and Arabs.”

Other histories of mathematics written by “dead white males” likewise include appreciative assessments of Egypt and Babylon, China, India, and the Islamic world. While it is possible such authors missed things in their accounts of non-Western mathematics — due either to the incompleteness of their own research or to historical knowledge that has been brought to light since their time — it is hard to detect any desire to conceal or trivialize non-Western achievements. To repeat: a self-confident people feels no need to deny or downplay the achievements of others, but the resentful may feel the need to accuse them of this.

After everything has been said that can honestly be said to the credit of the Egyptians and Babylonians, however, it remains true that before the rise of Greek mathematics we find: 1) a lack of interest in formal demonstration, 2) a failure to distinguish between exact and approximate results, and 3) collections of particular problems as opposed to logically ordered expository treatises.

And these qualities continued to characterize non-Western mathematical work until the beginnings of Western influence. According to Stuart Hollingdale’s Makers of Mathematics (1989), “Chinese mathematical works . . . are in the spirit of the Babylonians rather than the Greeks. They consist of collections of specific problems and present a curious mixture of the primitive and the sophisticated,” although over time their math eventually became “more advanced than the Babylonians in that they gave general rules, often with formal proofs.”

Joseph Needham disputes this last assertion, writing that Chinese mathematics lacked “the idea of rigorous proof.” He described Chinese algebra as utilitarian and concrete, “devoted to the problems ruling officials had to solve.” Chinese mathematics partook of “a mental outlook which avoided the development of formal logic and which allowed associative or organic thinking to dominate.”

When the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci first introduced China’s scholars to Western learning in the late 16th century, among the works that most deeply impressed them was an elementary geometry textbook from 300 BC. As Steve Farron notes in “Why the West Dominated,” first published in American Renaissance in December 2009, Fr. Ricci recorded in his diary that

nothing pleased the Chinese as much as the Elements of Euclid. This was perhaps due to . . . the Chinese . . . method of teaching, in which they propose all kinds of propositions but without demonstrations. The result of such a system is that anyone is free to exercise his wildest imagination relative to mathematics, without offering a definite proof of anything. In Euclid, on the contrary, they recognize something different, namely, propositions presented in order and so definitely proven that even the most obstinate could not deny them.

As Dr. Duchesne writes:

The Greeks were the first to derive mathematical concepts from pure reason alone, with little reference to the external world — that is, the first to think about numbers and operations abstractly, as products of the rational powers of man, and to realize that geometry is concerned not with physical objects, but with points, lines, triangles, squares, as objects of pure reason. They invented deductive reasoning, a method wherein reason proposes self-evident premises or axioms from which it deduces theorems in a rigorously consistent (and self-conscious) manner.

The familiarity of even educated Westerners today with Ancient Greece is often limited to having read some if its literary works in translation or seen references to Athens as the cradle of democracy — an absurdly inadequate basis for estimating Greek achievements. Sir Thomas Heath, author of a two-volume History of Greek Mathematics (1921), may well have been correct in observing: “Of all the manifestations of the Greek genius, none is more impressive and even awe-inspiring than that which is revealed by the history of Greek mathematics.”

Champions of “multicultural mathematics” sometimes appear confused as to the relation between the objective and universally valid results of this science and what we call “culture.” Euclid’s Elements were the product of a particular culture, namely, that of ancient Greece, and may even have been in part an expression of that culture (for example, of its having reached Piaget’s level of formal operational thinking). But Euclidian geometry is not culture-bound: the angles in a triangle add up to 180º everywhere.

Western discoveries and intellectual breakthroughs have benefited all mankind, and that is one reason we want to preserve the race responsible for them. This task is vastly more urgent than offering resentful people further fuel for their resentment.

Western greatness: not just the Greeks

Ricardo Duchesne’s Greatness and Ruin is a broad survey of the story of Western civilization interpreted as the rise of an autonomous, self-reflective human consciousness — a process that never developed independently in any other civilization. At least three important landmarks in this process preceded the rise of Greece: the Upper Paleolithic Behavioral Revolution (art, trade, better tools and shelter, rituals), the detachment of the male mind from the nature-bound female realm of fertility goddesses, and the Indo-European development of competitive aristocratic warrior bands not based on kinship. The first two may reasonably be credited to humanity as a whole; Western differentiation, on Dr. Duchesne’s account, is traceable to the Indo-Europeans.

The rise of Western self-consciousness hardly ends with the story of Ancient Greece. It continues with the development by Rome of an unprecedentedly rational system of law, with the rise of the world’s first rationally articulated religious faith once the young Christian church had assimilated the intellectual inheritance of Greece and Rome, and with the Church’s determined efforts to moderate the influence of extended kinship structures by championing non-consanguineous monogamy by consent.

The Medieval period saw the rise of voluntary associations such as urban communes, merchant associations, guilds, monasteries, and universities, with corporate rights of self-government each according to its own law. The university is perhaps the European institution par excellence: a self-governing body dedicated to the disinterested pursuit of truth and teaching. The Medieval university must not, of course, be confused with today’s similarly-named bureaucratic monstrosity devoted to the enforcement of ideological conformity and the suppression of the ideals and of the race of men which made its Medieval prototype possible.

Other highlights of Dr. Duchesne’s book include accounts of Europe’s decisive superiority in domains such as chemistry, geology, cartography, historiography, music, the visual arts, and literature.

Ten of the eleven chapters in Greatness and Ruin are devoted to analyzing and celebrating Western greatness, while the final chapter is reserved for its ruin, i.e., the contemporary crisis of white European civilization manifested most clearly in today’s mass immigration. Dr. Duchesne’s thoughts on this subject are so important that I will reserve them for discussion in Part II of this review.

The post The West: Both Our Own and the Best appeared first on American Renaissance.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: F. Roger Devlin

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://www.amren.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.