One of my closest friends and favorite humans is Anna Conkey, the founder and executive director of Neuroimmune.org, a non-profit dedicated to advocating for research into and physician education of PANS (pediatric acute neuropsychiatric disorder), a devastating illness triggered by certain childhood infectious illnesses.

Having lived through the catastrophic PANS (actually, PANDAS) illnesses of two of my three daughters, I was left with PTSD from the abject failure to diagnose and treat the first one despite 17 different encounters with emergency room physicians, pediatricians, neurologists, and psychiatrists. I met Anna soon after that journey and have been an active Board member of Neuroimmune.org ever since, long before Covid (Anna will kill me if I do not include a donation link).

Anyway, Anna was searching for an old email in her inbox when she came across one from me from years ago, where I related a story to her that had just happened to me. She re-read the email and laughed so hard she cried.. again (she still doubles over laughing and crying every time she or I bring up the story). It was early on in my Substack career, so she immediately called me and demanded that I do a Substack post about it because, “It. Is. My. Favorite. Story. Ever.”

Even though I am the butt of this joke of an episode in my life, it’s a welcome change from my usual drum-banging around Covid corruption and medical system insanity. I trust it will bring a smile and even a few laugh-tears to my dear subscribers. We sure could use one.

Anyway, here goes. Please note all names and places have been changed to preserve anonymity.

I was once in charge of the ICU of a large hospital as well as the Director of a training program for doctors wanting to become specialists in Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. At one point, I worked closely with a medical device company representative to build a custom central venous catheter insertion kit. This kit aimed to help my critical care fellows and medicine residents insert them in as sterile and efficient a manner as possible.

Placing such catheters is one of the foundational procedures that a critical care physician must master, and maintaining a sterile field during an ongoing resuscitation of a crashing patient is paramount to avoid bloodstream infections. This isn’t what this post is about, though.

One Sunday morning, I received a call from the device rep. I was pretty shocked because device reps usually don’t call ICU Directors… on a Sunday morning (I was not working that day either).

He started by apologizing for bothering me on a Sunday, but we were pretty friendly, so I asked him, “What’s up? How can I help you?” He then started telling me about how his wife is one of the operational leads at the local zoo. I wasn’t sure where this was going, but then he began to explain that the zoo needed my help.

The zoo had a very sick teenage orangutan named Winaka (not her real name, but close) who was suffering from acute paralysis, and the veterinary team thought she had fallen ill with tetanus. They needed to get nutrition as well as medicines into Winaka because she could no longer raise her arms to feed herself or even hold herself up. He mentioned that the veterinary team was seeking an expert in inserting central venous catheters and asked if I could assist, as the veterinarians do not perform this procedure in their practice.

As tired as I was on that morning, I immediately jumped up, as the opportunity to be involved with caring for a critically ill orangutan was beyond exhilarating to me. Let alone the fact that my Hippocratic oath dictated that I help anyone in medical need when asked (not sure if the Hippocratic oath mentioned orangutans, but you get it).

So I said, “Absolutely, I’ll go over there right now, let me just pick up my equipment from the hospital.” He laughed and explained that it couldn’t be done today because they needed to get a lot of things in place first. Apparently, you can’t just walk into a cage with an orangutan and ask them to lie quietly while you insert a central line into their femoral vein. In fact, nobody at the zoo ever enters their cage because they can snap your arm off when scared or excited, except perhaps in cases like you see on TV, where they know you from birth, etc.

He explained that in the morning, they would first sedate Winaka, bring her into the treatment room at the zoo, then an Anesthesia team from the hospital would be there to intubate her and attach her to a ventilator so that we could place the central venous catheter. He put me in touch with the veterinarian, and we discussed the case at length (I probably asked a hundred questions as I was endlessly intrigued). I became quite fascinated, not only with the medical history but with the history of this orangutan.

I learned that Winaka was a very smart and very suspicious orangutan. They had never been able to hide any pills or medicines in her food, not even in yogurt or ice cream, because she would NEVER touch anything they had messed with beforehand. Know that this method was their standard approach to administering needed medicines to all their animals, but Winaka never fell for it. Like I said, fascinating.

Other weird stuff in her history was that she once had a baby, but didn’t like the baby and was mistreating it, so they had to take the baby away. Apparently, this happens sometimes with young teenage mother orangutans. Another fun fact: orangutans spend the first 8 months of their life draped on the chest of their mother. Like 24/7.

Given Winaka’s mistreatment of her baby, they had to take it away from her. So what did they do? They hired staff who worked in shifts day and night, holding the baby orangutan on their chest, wearing it like a fur vest, and they bottle-fed her that way. When I met one of the former “surrogate orangutan moms” at the zoo, she told me that the shifts were hard because she had to hold their pee for hours, because, if she went to pee, it required peeling the baby orangutan off her warm chest, which was very distressing to the baby orangutan.

The zookeeper team was very proud of their efforts, especially the ending where they were finally able to bring the baby orangutan to a zoo across the country where a mother orangutan had recently lost their child. When they presented the baby orangutan to the mother orangutan, it was a match made in heaven, and they have lived closely and happily together ever since.

Let’s get back to the story at hand. As soon as I got off the phone with the rep, I sent a group text to all my fellows (senior physician trainees in critical care medicine), and they immediately started to blow up my phone. All were begging to be chosen to come with me to the zoo. My favorite was when one of my fellows, who was on vacation across the country at the time, texted back, “I am getting on a plane right now.” Anyway, I selected the two fellows who wouldn’t be on service the next day, and we all made plans to go to the zoo in the morning with our ultrasound machine and central venous catheter equipment.

Fast forward to the next day, when we arrived, the team of anesthesiologists was already there, as well as a neurology team (they were there to do a spinal tap, also something not commonly done by veterinarians). The anesthesiologists were already working on inserting a peripheral IV to administer medicine to perform the intubation.

I will just leave you pictures of that day and then we’ll get to the meat of the story.

Picture #1: An anesthesiologist is looking for a vein to insert a peripheral IV

Photo #2. The anesthesiologist is “pre-oxygenating” Winaka in preparation for insertion of an endotracheal tube

Photo #3. Anesthesiologist is opening the jaw in preparation for insertion of the laryngoscope

Photo #4. The anesthesiologist begins to open the jaw with the laryngoscope in order to visualize the vocal cords for placement of the endotracheal tube.

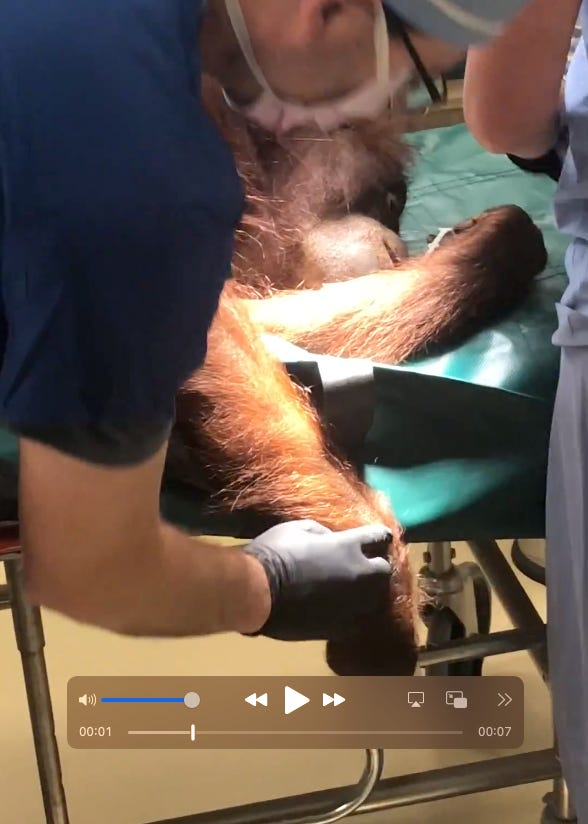

Photo #5. We splay open Winaka’s legs to prepare the field for insertion of the central venous catheter in the right femoral vein (in the right groin)

Photo #6. My fellow placing the central venous catheter. Winaka is chilling out under Anesthesia.

Photo #7. The neurologist is performing a lumbar puncture (spinal tap) to obtain cerebrospinal fluid for analysis.

All procedures were successful. Winaka was then immediately administered critical antibiotics, along with other medicines, as well as intravenous nutrition. All teams were quite proud of their work.

Over the next ten days, I got consulted multiple times on various aspects of Winaka’s treatment, none more memorable than when they called to tell me Winaka’s right leg was double the size of her left. Ugh. Deep venous thrombosis (DVT).

I again went down there with my ultrasound machine, diagnosed the DVT and we started her on blood thinners. I also had to counsel the veterinarian team on what to do if Winaka “threw the clot to her lung.” This is called a pulmonary embolus and can cause a medical emergency or even cardiac arrest if large enough (it was large). We arranged to get a powerful clot-busting medication to have on hand in the event it were to happen—another day in the life of a critical care orangutan doctor.

Now, please realize, we are not at the funny part yet. What happened next is that my team (which included a partner of mine) wanted to write up the case and publish it as a “case report” for an upcoming national conference we were all going to. We thought it would be interesting to discuss the application of ultrasound in the diagnosis and treatment of a critically ill orangutan. Plus, the pictures were cool :).

Anyway, we asked the veterinarians to co-author with us; they were excited to write it up as well, but they told us we needed to get permission from the zoo first. So, I asked one of my fellows to write to the Zoo Director and ask for permission. In the below email exchanges, I have changed or redacted all names and emails:

From: Dr. Smith

Sent: Thursday, October XX, YYYY

To: Zoo Director

Cc: Pierre Kory ; Dr. Jones

Subject: Abstract RequestDear Deputy Zoo Director,

We are part of the ICU Medical team that evaluated and helped treat your orangutan, Winaka, several weeks ago for her quadriparesis and deep vein thrombosis. We were thrilled to have the chance to interact with Winaka and hope we were able to contribute to her remarkable recovery.

Use of ultrasound is increasing amongst ICU physicians but remains underutilized, particularly for identification of deep vein thromboses. We hoped to submit an abstract describing Winaka’s case at one of our pulmonary and critical care meetings (American Thoracic Society), to increase excitement and promote the use of bedside ultrasound.

The fact that she is an orangutan will undoubtedly increase interest, and we hope it will stimulate improved uptake of ultrasound technology. I have attached the abstract, which we hope to submit on October 29, for your review to ensure it maintains the confidentiality of the Zoo and the accuracy of the case. We have already had it reviewed by the veterinarian team of doctors.

Thank you for your consideration. We would love to assist with any future cases if we can be of service.

The Zoo Director’s reply:

On Oct 17, , at 5:54 PM, Deputy Director of the Zoo wrote:

Dr. Smith,

The entire Zoo is grateful for the support and expertise shared from the local medical community during our time of need and uncertainty. It goes without saying, the intent of everyone’s focus was to improve Winaka’s quality of life. And as a result, a community of like-minded professionals and talents came together for one common goal.

There is still a lot we don’t know, and a lot we still need to discover. Over the next several months, the zoo’s leadership team will be working closely with the Orangutan Species Survival Plan (SSP) and the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) steering committees. Our zoo’s Executive Director, who leads one of these committees, will establish message points and timelines for how information regarding Winaka’s case gets released, and for what purposes.

At this time, we cannot approve this abstract for submission. This is not to say future considerations won’t be accepted, but for the moment, we’ll need to put this on pause.

As the Zoo establishes best practices in medical care for our collection, we are also developing a comprehensive plan to communicate, educate, and teach these practices. We hope you understand our decision at this time; furthermore, know that the success of Winaka’s recovery, and all of our zoo’s collection, relies heavily on our community’s continued support.

Respectfully,

Deputy Zoo Director

Here is where.. I really effed up. I was so disappointed at his denial of permission to publish an abstract that I blew off some steam in an email to my colleagues, where I “replied all,” not realizing that the Zoo Director would receive it (I thought my colleague had personally forwarded me the above exchange, not cc’ed me). Whoops.

*Sorry to leave you hanging here, guys, but due to my embarrassment and the “indelicateness” of my reply, I am only comfortable sharing with my paid subscribers. This community, I know, will not only forgive but also laugh rather than critique me negatively. I hope the rest of you enjoyed the above episode.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Pierre Kory, MD, MPA

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://pierrekory.substack.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.