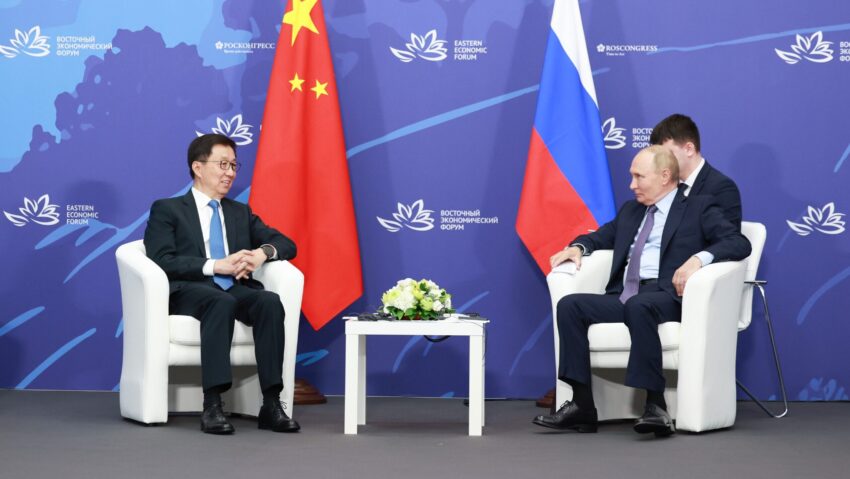

Chinese Vice President Han Zheng meets with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Vladivostok, Russia, Sept. 4, 2024. (Photo by Wang Ye/Xinhua via Getty Images)

American B-2s just set the Iranian nuclear problem back by years. Syria is no longer a basket case. And the Trump administration has secured a commitment by NATO members to spend 5 percent of GDP on defense.

The United States can finally pivot to Asia, right? Wrong.

Every president of the 21st century has sought to reorient the American ship of state to focus on the Indo-Pacific, where China’s rise has increasingly threatened US national security interests. But Europe and the Middle East keep getting in the way.

The desire to pivot, a phrase coined by former secretary of state Hilary Clinton, is understandable. The People’s Republic of China is a totalitarian state that believes it is entitled to inherit the earth, one with unlimited economic, territorial, and nuclear ambitions that, if realized, would leave the postwar world the United States shaped in tatters.

Yet attempted pivots — particularly those under President Barack Obama, President Donald Trump’s first term, and President Joe Biden — fostered the chaos elsewhere that led those attempts to fail.

Obama’s announcement of a rebalance to Asia and subsequent withdrawal from Iraq created a vacuum that Iran, the Islamic State, and Turkey were delighted to atrociously fill. His disdain for Europe and desperation to make nice with Vladimir Putin, meanwhile, paved the way for Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine. The Obama administration spent the years after its initial shift to Asia moving forces back into the Middle East and Europe to quell the violence and deter further aggression.

Trump reoriented America’s China policy, labeling Beijing a strategic competitor and launching initial efforts to constrain its growing power. The administration looked at Russia and malevolent Middle East actors as, respectively, second- and third-order priorities. Biden adopted this approach and carried out the Afghanistan withdrawal his predecessor had negotiated with the Taliban. The result should not have come as a surprise to the many Obama veterans in the Biden administration, including the president himself: the largest land war in Europe since World War II and a Middle Eastern war in which Israel fought on seven fronts.

Both Ukraine and Israel are escalations of existing, years-long, low-intensity wars, which broke out and continued due to the downsizing of the US presence in the respective regions. The Obama administration reduced military capabilities in Europe in its first term; when Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014, there was not a single American tank in Europe for the first time in decades. The rise of the Islamic State was a result of withdrawal from Iraq and a conscious decision to husband resources and abstain from intervention in the Syrian Civil War. The Islamic Republic’s deployment of its military to Syria and close to the Israeli border set off the shadow war between the two.

China took advantage of these escalations. It fed Russia’s war machine and kept the Russian economy afloat with energy purchases and the provision of materiel. After Oct. 7, 2023, China openly sided with Hamas and sought to use that support to stoke discontent on the “Arab street,” creating political challenges for America’s regional allies. The Biden pivot to Asia was, like its forebears, abortive. The administration shifted from prosecuting a competition with China to managing it so it could focus its energies on hot wars elsewhere.

The current Trump administration entered office with a bias toward “prioritizing” Asia, but reality again intervened. The administration has had to dedicate time and resources to the conflicts in Europe and the Middle East. For reasons of economics, security, and values, both regions remain enormously important to the United States — and to America’s allies and partners in Asia, which depend on energy imports from the Persian Gulf and on trade with the European Union.

Pivots to Asia are destined to fail as long as there are bad actors elsewhere on the Eurasian continent. If the United States is serious about containing China, it must ensure that events elsewhere do not disrupt Asia policy. Otherwise, China will grow ever stronger and ever more disruptive.

This requires American leaders to accept that Eurasia is best understood as a cohesive political space, rather than a collection of disparate subregions. Eurasian order is unitary: It is not possible to ensure tranquility anywhere on the continent without ensuring it everywhere.

Rather than pivot, rebalance, or prioritize, the wise choice is for the United States to grow its military and recommit to exercising hegemony in Eurasia, the role it adopted in the wake of World War II. It should set its eyes on remaining the dominant economic, scientific, and military power in Europe, the Middle East, and the Indo-Pacific. The world’s wealthiest country can afford this.

Asked what guided his administration, UK Prime Minister Harold Macmillan is alleged to have said, “Events, my dear boy, events.” The United States should actively maintain the Eurasian order if it wishes to contain China and prevent distracting events in Europe and the Middle East. Otherwise, it will not be until war with China breaks out that the pivoters finally get their wish.

Shay Khatiri is vice president of development and senior fellow at the Yorktown Institute. Michael Mazza is a senior director at the Institute for Indo-Pacific Security (formerly the Project 2049 Institute) and senior non-resident fellow at the Global Taiwan Institute.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Shay Khatiri and Michael Mazza

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://breakingdefense.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.