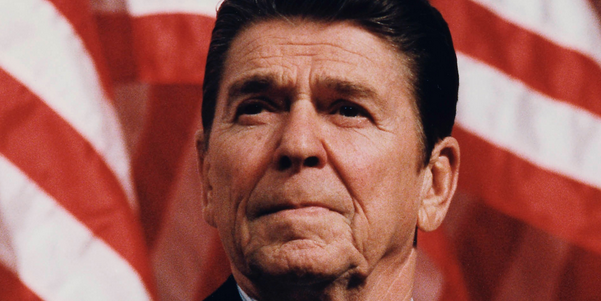

President Trump has proposed that to “protect our homeland” he would move ahead with a Golden Dome missile defense. The Department of Defense is seeking a hefty budget increase for it next year, but the program is controversial. Missile defense was contentious also in the 1980s when President Ronald Reagan offered a vision to render nuclear weapons “impotent and obsolete.” Golden Dome proponents might avoid some of the disputes of the SDI era.

Golden Dome recalls Reagan’s concept for SDI to defend the U.S. against long-range ballistic missiles. It was seen as futuristic or infeasible. Although controversy weakened support for SDI, ever since Reagan’s presidency Congress has funded work on long-range missile defense. This is in addition to Congressional backing for tactical ballistic missile defense to safeguard U.S. forces on land and at sea.

What lessons from the politics of SDI might be helpful for Golden Dome?

Don’t exaggerate. Reagan’s vision was seen by many as other-worldly, sapping SDI’s credibility. A 1987 American Physical Society study said directed energy technologies, if ever to work, needed gains of a hundred times or more. Rigged tests spawned criticisms. A Reagan decision document warned of a Soviet missile defense “breakout,” but the USSR was lagging.

Edward Teller, a hydrogen bomb designer, touted to Reagan the idea of an x-ray laser powered by a nuclear explosion in space, possibly over the heads of Americans. Teller lost ground when he claimed a laser could shoot down the “entire Soviet” land-based missile force. The Reagan administration soon vetoed this concept, clarifying that SDI would be nonnuclear only.

Go step-by-step

Part of SDI morphed into the early deployment of ground-based interceptors. Meanwhile research continued on advanced concepts, such as space-based kinetic kill defenses. One early concept, Brilliant Pebbles, envisioned large numbers of small interceptors in low earth orbit. Brilliant Eyes in space could detect, discriminate, and pass targets to space- or ground-based interceptors.

Aim for bipartisan support

Reagan’s unveiling of SDI stirred sharp partisan anger. A decade later, Democrats were still lambasting SDI. In 1993, Secretary of Defense Les Aspin bragged of “taking the stars out of Star Wars.” A less partisan and more realistic initiative might have lowered temperatures.

Cultivate allies

Many U.S. allies worried that SDI was infeasible or might be destabilizing. But they also saw it as helping to bring the Soviets to the nuclear negotiating table. While France strongly criticized SDI, it rejected a Soviet bid to jointly denounce it. The Reagan administration reduced anxieties by offering allies cooperative research on advanced SDI technologies.

Be straightforward

In 1987, the Reagan administration stirred a hornet’s nest in the Senate by asserting a “broad” interpretation of the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. This could have allowed SDI field testing previously thought to be banned. In 2002, the U.S. took a more direct approach by withdrawing from the Treaty. Designed for an earlier era of nuclear-armed interceptors, it unduly constrained the exploration of nonnuclear defenses.

Rely on evidence-based analysis

Major U.S. defense programs are subject to a thorough review process. Some SDI proponents raised hackles by seeking to bypass it.

In recent years, regional conflicts have shown the value of defenses against tactical ballistic missiles. U.S.-made Patriot interceptors are helping Ukraine to defend against Russian missiles. Last October, Patriot and U.S.-made SM-3 and THAAD interceptors aided Israel’s successful defense against a large Iranian attack. Defense against long-range missiles is more challenging. Target speeds are higher, and decoys and other penetration aids can confuse interceptors.

Since 2004, the U.S. has deployed in Alaska and California a few dozen Ground-Based Midcourse Defense (GMD) interceptors meant to defend the whole country. GMD’s mixed success in field tests, however, has drawn criticism. But the system serves important if limited purposes. It might help defend against potential small, accidental, or unauthorized attacks.

A Golden Dome defense will be technically demanding. Some may argue that adversaries could build added offensive missiles less expensively. Some might urge that defense resources be used for other purposes, such as building drones or countering China in the Indo-pacific.

Past disputes over SDI and GMD could help spur debate about Golden Dome’s future. Applying lessons from them might help put Golden Dome on a sounder footing.

William Courtney is an adjunct senior fellow at RAND and professor of policy analysis at the RAND School of Public Policy. In a career in the Foreign Service, he was deputy negotiator in the U.S.-Soviet Defense and Space Talks in Geneva (on missile defense) and ambassador in negotiations to implement the Threshold Test Ban Treaty.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: RealClearWire

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://www.wnd.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.