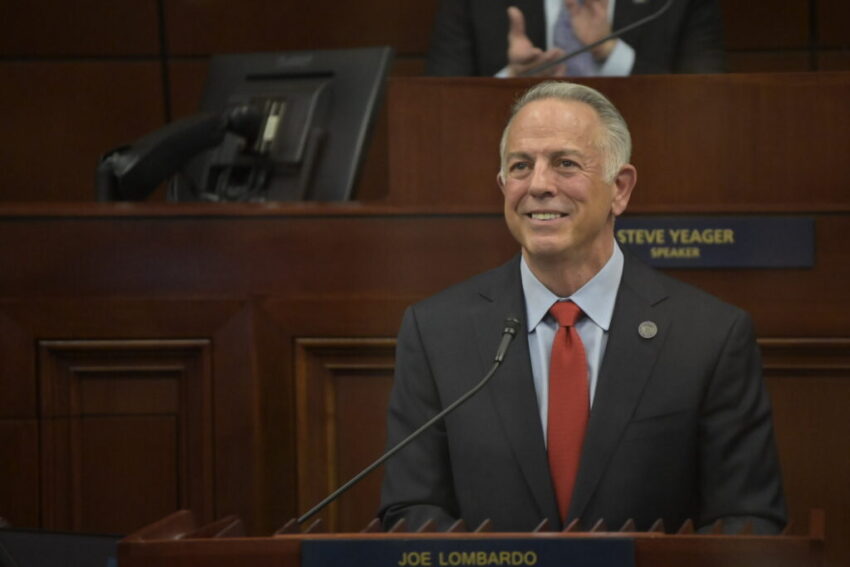

(Photo: Ronda Churchill for Nevada Current)

Gov. Joe Lombardo made righting Nevada’s economy a focus of his gubernatorial campaign. Now, as he begins his quest for re-election in 2026, critics contend he has failed to fulfill two central promises – to make housing more affordable and to lower the unemployment rate.

Lombardo’s policies on housing and employment often appear at odds with his goals, say observers.

“He has no intention of lowering rents or increasing availability of affordable housing, and that became apparent,” says Shelbie Swartz, executive director of Battle Born Progress, pointing to Lombardo’s enlistment of a Republican lawmaker to kill a measure that would have capped corporate investment in residential housing.

On the employment front, sacked with the highest jobless rate of any state for the last year, Lombardo pursued an anti-worker agenda, critics contend, including a veto of legislation that would have required paid family and medical leave for employees of some private companies.

The governor did not respond to numerous requests for comment for this story.

‘Trickle-down housing’

Of a handful of bills championed by Lombardo this year, only two passed – an education reform measure and a housing act aimed at reducing demand across the spectrum by creating a new level of subsidized housing for buyers earning up to 150% of area median income (AMI).

Subsidized housing is currently reserved for individuals earning up to 80% of AMI, and in some cases up to 120%.

“It’s kind of like a trickle-down housing policy,” says Ben Iness of the Nevada Housing Justice Alliance. “Are middle-income folks those that need support the most? Are they in dire straits compared to our low income and extremely low income residents?”

The idea behind the policy is that more market-priced, ‘attainable’ homes will free up existing units for low and extremely-low income Nevadans, who have fewer choices than low-income Americans in any other state.

“The trickle-down theory doesn’t work,” says Las Vegan Frank Hawkins, who has built thousands of low-income and affordable units in Nevada. “It’s like saying I’m gonna give you nothing and I’m gonna give you more of it, and sooner or later, you’re gonna have something.”

Yet, Hawkins, a former Las Vegas city councilman, is excited the law facilitates construction of properties for sale, rather than for rent, and is hopeful Lombardo’s plan will spur gentrification in distressed areas such as the Historic Westside, where dozens of vacant parcels are owned by the government, even if it’s unlikely developers will pursue the opportunities.

“Builders want to be out in the suburbs,” he said. “And they want everything to be on new streets, for new people.”

In Clark County, where the area median income for a household of four is estimated at $75,000, a buyer earning $112,000 would be eligible for Lombardo’s plan. The threshold would be slightly higher in Washoe County, where the AMI is $83,800.

At that income level, a prospective buyer could qualify for a home valued at roughly $460,000.

The median price of a single family home in Clark County sold in May was $480,000, up from $425,000 when Lombardo took office in January 2023. The median price of a home sold in Reno was $595,000, up from $510,000 when Lombardo took office. Rent at both ends of the state is also up from when Lombardo became governor.

The housing act was initially slated to cost $250 million and serve 16,000 households, but was scaled back to $133 million with a goal of creating 5,000 single-family homes.

Lombardo has access to other incentives that don’t require public funding, such as inclusionary zoning, a policy that requires developers to include a certain percentage of affordable housing units in new residential developments or pay into a fund that does the same.

As a candidate, Lombardo, a free-market enthusiast, rejected proposals such as rent stabilization and inclusionary zoning. Instead, he said he’d “provide incentives and defer payments on land” to generate more affordable housing.

Supporters of Lombardo’s legislation reject the notion that it ignores the need in low- and extremely-low income markets. Nevada has 14 units for every 100 extremely-low income residents, the lowest level in the nation. Other programs, they note, such as federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC), are doing the work to develop units at the low end of the market.

“Nevada’s housing crunch is not limited to affordable units. It is a system-wide shortfall,” says Wally Swenson of Nevada HAND, which facilitates low-income housing development. “Families at every income level are competing for too few homes, which results in rising home prices, forcing more competition for both naturally occurring and purpose-built affordable housing.”

Middle-income buyers, Swenson says, are “edging out neighbors with lower incomes.”

While housing reserved for low-income residents is essential, building at every price point, he says, “is a sustainable strategy to address the downward pressure on affordable housing and support our growing communities.”

Ennis of the NHJA questions whether federal funding for low-income housing will fall victim to President Donald Trump’s cost-cutting. “It’s hard to suggest our state is immune from what’s happening nationally.”

The LIHTC program is not currently in jeopardy, In fact, both parties have voiced support for expansion of the credits.

While housing construction lagged growth in the decade from 2010 to 2019, a surplus of units built before the Great Recession has picked up the slack, say a chorus of experts who contend the housing shortage is manufactured.

“Unfortunately, not enough of it is affordable, especially for low-income and very low-income families and individuals,” says Kirk McClure, a Kansas University professor who co-wrote a study published in the journal Housing Policy Debate.

Affordability challenges, he says, are a result of low incomes versus high housing prices, rather than a shortage.

“This condition suggests that we cannot build our way to housing affordability,” he says. “We need to address price levels and income levels to help low-income households afford the housing that already exists, rather than increasing the supply in the hope that prices will subside.”

Iness of NHJA agrees. Absent solutions for low wages, tenant protections, measures to keep rents in check, enforced habitability standards, and controls on corporate purchases of residential units, Lombardo’s policy, he says, seems superficial.

Giving away the house

Builders, who learned they can make higher profits by selling fewer homes, are not building much, and when they do, it’s not the multifamily units that are desperately needed, especially in Southern Nevada. In 2023, Reno and Sparks issued 15% more multi-family building permits than Las Vegas, Henderson, and North Las Vegas combined, reports the Guinn Center for Policy Priorities.

Thanks to inflation, the high cost of capital, and the cost of materials, “a lot of projects just don’t pencil in anymore,” says Nicholas Irwin, research director at UNLV’s Lied Institute. “On those lower-income projects, the capital financing is just not there, or the cost of construction is just so high. Given a choice with a piece of land, developers know if they can get more of an upper-end of market distribution, that’s their target.”

Whether Lombardo’s effort frees up units that can be filled by low-income earners remains to be seen, says Irwin. “Whenever you expand eligibility, those programs are going to help get more people into housing. We don’t know if it’s going to be the people at the very low or upper distribution of that spread.”

Subsidies for affordable housing are designed to solve the resulting math problem when development doesn’t add up. Gap financing, low-income housing tax credits and other subsidies guarantee the project and its resulting below-market rents won’t be a drain on developers.

Until recently, such programs have been reserved for critical efforts to provide units for low and extremely low-income residents, who are often seniors and others on fixed incomes.

“What we’re seeing now is the markets underproviding middle-income housing as well,” says Irwin. “We need to build more housing of all types.”

Irwin notes other states are using public money to incentivize developers. Colorado lawmakers are shoveling public money into housing projects targeting households earning as much $170,000 a year, the Colorado Sun reports.

Legislative insiders suggest that politics, not policy, is the impetus for Lombardo’s housing gamble, which enhances the governor’s bona fides with voters, apart from any ties that may bind him to Trump.

He is expected to face off against Attorney General Aaron Ford, a Democrat.

Six of eight Republican state senators voted against Lombardo’s housing bill, which had widespread support from Democratic lawmakers and passed unanimously in the Assembly.

‘An unusual twist’

On the campaign trail in 2022, Lombardo blamed then-Gov. Steve Sisolak for the state’s unemployment rate, and suggested it was under the governor’s control.

Under Lombardo, the state has led all others with the highest unemployment rate in the nation for the last year, and the job growth rate is the fourth lowest in the nation.

In his 2025 State of the State address, the governor noted that under his watch, a record 1.6 million Nevadans are on the job. “But in an unusual twist, Nevada’s unemployment rate stands at 5.7 percent – a number that reminds us there is still much work to be done.”

Lombardo acknowledges that, for the most part, his initiatives are intended to appeal to employers, not to the workers he seeks to enlist.

“Nevada has long prided itself on maintaining a business-friendly environment,” Lombardo said in his veto message of a bill that would have required businesses with more than 50 employees to provide 12 weeks of paid family and medical leave. Current law requires 8 weeks of PFML leave, but only for state employees.

In two legislative sessions and in public appearances, Lombardo has eschewed worker-friendly policies, such as prevailing wage, a provision initially exempted from his housing bill, and he’s laid the blame for the state’s jobless rate on its residents.

‘We’re number one in job availability, but we’re number one in unemployment, you know why? Because they’re not quality jobs,” he said at a Republican gathering this year. “People would rather manipulate the government process and receive unemployment or to sit at home versus occupying a job that’s available that doesn’t see their family moving forward.”

Lombardo’s economic development bill contained a rare pro-worker initiative that would have provided transferable tax credits to help finance a new or expanding child care facility for up to five years. It went nowhere in Carson City.

His efforts to diversify the economy have “brought $5 billion in economic development into the state,” he told a Republican gathering in April. His Office of Economic Development notes 41 companies have made $6.7 billion in capital investment during his term. More than half of the investment – $3.6 billion – is from Tesla, Inc., which had a footprint in the state before Lombardo took office.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Dana Gentry

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://www.nevadacurrent.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.