A Blueprint for NIH Reform

by Martin Kulldorff at Brownstone Institute

Abstract

Both scientists and the public are frustrated with the scientific enterprise. Scientists spend considerable amounts of time writing grants that are not funded. The publication process is tedious. There is a lack of open scientific discourse, leading to questionable medical and public health practices and an increasingly distrustful public. Change is needed, and this Perspective presents a blueprint for NIH reforms with the dual goal of ensuring scientific integrity and innovation, which is needed to restore trust among the American public who generously fund NIH through their taxes.

Introduction

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) failed us during the Covid-19 pandemic, by advocating for unscientific school closures, lockdowns, masking and vaccine mandates, and by stifling scientific debate. NIH used to have broad support from the public across the political spectrum, but that ended during the pandemic. For the progress of science and the scientific community, it is critical to restore that broad support. The key is a return to innovative and evidence-based medicine, and for that eight things are needed: (i) Allowing scientists to do what they view as their most innovative research concerning the most important health issues. (ii) More large sample size reproducible research. (iii) Efficient use of financial resources. (iv) Efficient use of the precious time of scientists. (v) Thorough peer review evaluation of funded research. (vi) Open scientific discourse and the restoration of academic freedom. (vii) Decentralization of science. (viii) Elimination of both actual and perceived conflicts of interest.

To help achieve that, here is a proposed twelve-point program for major reforms at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

1. INVESTIGATOR-INITIATED RESEARCH GRANTS

The core NIH activity is the funding of investigator-initiated extramural research at universities, hospitals, and other research institutes across the country, with RO1 grants as the primary mechanism. NIH funds many excellent and important research projects, but it is an inefficient system with six major problems.

(i) Scientists must write between two and a dozen grant applications for every funded grant received. Writing unfunded research proposals is a waste of effort. That time is better spent on doing actual research.

(ii) Among the many grants submitted by a scientist, it is not always what they view as their best grant applications that get funded. This means that scientists spend a lot of time on what they themselves view as less innovative and important research.

(iii) With NIH funding, the time between conceiving a research idea and receiving funding to start the actual research is at least one year but usually more. This slows down scientific progress.

(iv) Research grants are evaluated and funded based on what scientists promise to do in proposals submitted to NIH, but it is more difficult to judge the quality of proposed research compared to research that has been completed and published.

(v) When writing grants, scientists face a dilemma. They must include enough data and results to convince the reviewers that the research is promising, without already doing major parts of the work. This forces scientists to conduct many small underpowered preliminary studies of limited value. The need for existing evidence and promise is also detrimental to the most innovative and breakthrough research, which tends to be riskier.

(vi) While scientists must send progress reports to NIH, there is not sufficient and open evaluation to determine the quality of NIH funded research articles.

PROPOSAL #1:

To give scientists the freedom to do the research they consider most innovative and promising, grants should be awarded based on evaluation of their three best first-authored articles published during the past five years, rather than promises about proposed future work. If scientists have done excellent research in the past, they will continue to do excellent research, and this system will allow scientists to quickly pursue interesting new ideas. It also means less time spent on grant writing, and more time spent on research. To ensure funding for a wide range of research areas, scientists would specify their area of research, such as genetics, diabetes treatment, or cancer epidemiology, and each area would have a defined amount of NIH research dollars to distribute to the scientists in that area. To ensure research collaboration, there should be a maximum amount of the grant that can be used for principal investigator salary.

NIH already has some funding opportunities along these lines, which can easily be expanded. If there are doubts about this new approach, one option is to let universities choose between the old and this new system. Vinay Prasad has argued that different NIH grant award mechanisms should be put to the same rigorous scientific evaluation as science itself, by randomizing scientists or universities to different grant systems.1 With that philosophy, universities could be randomized to either the old or this new system, followed by a thorough and comparative evaluation of research results.

2. TRAINING GRANTS FOR YOUNG SCIENTISTS

It is more important than ever that NIH provides K01 training grants for young scientists that do not yet have the credentials to compete for regular grants. The current process is inefficient though. After finishing their studies, prospective young scientists must first apply for a junior position at an institution. Once hired, they often spend their first year writing a K-award proposal, which may or may not be funded after being evaluated by scientists at other universities. Whether eventually funded or not, their careers are delayed.

PROPOSAL #2:

NIH should allocate a certain number of five-year training grants to each medical, dental, and public health school in the United States, trusting them with finding the best young scientists to recruit, and letting them immediately start the research they want to pursue. Each medical school would receive at least one new training grant every year, while additional awards depend on the evaluation of research articles by recently supported trainees. To avoid academic inbreeding and ensure competitiveness and excellence, training awards should be used to recruit young scientists educated at other institutions.

3. SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS AND PEER REVIEW

Scientific peer review is critically important, but it is an inefficient and secretive process.

The scientific publication process is slow, frustrating, and time-consuming for scientists. Even good articles may have to be submitted and resubmitted to multiple journals before they are published. Reviewers do their important work for free, leading to a wide variety in peer-review quality. Most bad research is eventually published somewhere, getting the stamp of approval as gold standard ‘peer-reviewed research,’ but readers are unable to read any of the critical reviews.

Scientific publishing is also very expensive for taxpayers. It has been estimated that roughly $1.5 billion of the annual $48 billion NIH budget goes to the scientific publishing industry rather than to scientists doing science,2 both through indirect grant charges used by university libraries for expensive journal subscriptions and through journal publication fees. Compared to preprint servers like medRxiv, the only added value provided by these journals is peer review, but neither NIH nor the public can read the peer reviews they are paying for. To enhance the quality of NIH funded research, we must continuously, thoroughly, and openly evaluate the quality of it, just like any other product.

An increasingly sophisticated public wants open access to medical research, both for themselves and for their physicians, so that they can make informed decisions about medical treatment and prevention. The previous NIH director, Monica Bertagnolli, ordered that all NIH funded research must be published using open access, so that it can be freely read by anyone.3 That is a great step forward, but more is needed.

PROPOSAL #3:

To enhance open evaluation of scientific research, NIH should require all funded research to be published in open peer-review journals where signed reviews can be freely read by anyone at the same time as the article is published. While NIH cannot force journals to pay reviewers, NIH institutes can set up an open peer-review journal where any of their funded research can be published in less than a month and where reviewers are paid $1,000 for each review. For NIH-funded research published in other journals, NIH should organize, pay for, and publish independent peer reviews by a rooster of methodologically astute scientists.

There are a few open peer-review journals, including the British Medical Journal and eLife, but none that pay reviewers. As proof of concept, the newly launched Journal of the Academy of Public Health does both.4 Open peer review is not only important for NIH to be able to evaluate the quality of the research it funds. It also enhances open scientific discourse while giving reviewers public recognition and a citable reference for their important work. Especially young scientists benefit from reading an open exchange between more senior scientists.

4. SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS

It is important for NIH to not only fund original research but also the consolidation of existing knowledge in systematic reviews. What is the best prostate cancer treatment? Do the benefits of tonsillectomy surgery outweigh the risks? Should we use aluminum preservatives in vaccines? Do face masks reduce or increase infections? Can SSRI’s cause akathisia? The list is long.

In geography, atlases provide detailed guidance about every location on earth. The same is needed for all areas of medicine and health. Cochrane reviews served this purpose until the organization was captured by special interests, leading to the forced dismissal of one of the world’s most ardent advocates for evidence-based medicine, Dr. Peter Gøtzsche, and subsequent board member resignations in his support.5

PROPOSAL #4:

Taking over the mantle from the faltering Cochrane collaboration, NIH could fund rigorous evidence-based ‘Atlas Reviews’ on important clinical and public health topics. Coordinated by NIH staff, an external research team would first be funded to write an evidence-based systematic review, based on the available literature. In a second step, NIH convenes a meeting where the systematic review is presented and openly discussed by scientists with different perspectives. To avoid conflicts of interest, it is important that all participants are independent scientists without industry funding.

Funding scientists to engage in such open scientific discussions is just as important as paying them to do original research. The result of these Atlas Reviews may either be a consensus statement or well-articulated divergent views among the participants. The latter is not necessarily a failure but would inform NIH of high priority research areas that need to be funded through its requests for proposals mechanism (RFPs).

5. LARGE LONG-TERM RESEARCH STUDIES

As scientists, we conduct too many research studies with too small sample sizes that cannot give reliable effect estimates to determine if an intervention is working or not. This is a major problem and a significant contributor to the reproducibility crisis in medical research. Important and reliable discoveries are most likely to come from long-term large sample-size studies such as the Framingham Heart Study,6 which started in 1948, and the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial.7 Such large reliable studies are desperately needed for cancer, cardiovascular disease, auto-immune diseases, mental health, children’s chronic diseases and vaccines, among other areas, using both observational and randomized study designs.

PROPOSAL #5:

NIH should fund more long-term observational and randomized studies with large sample sizes. Because of extensive investments and logistical challenges, they cannot be confined or controlled by a single research group. With one group responsible for study design, data collection, and data management, the collected data should be available for any scientist to analyze and interpret.

When different scientists ask questions from the same data, this set-up can result in multiple research groups publishing similar study results around the same time. While this is a departure from current practices, it would be a good thing. If different scientists come to similar conclusions using different analyses, that strengthens the evidence. If they come to different conclusions despite using the same data, that sets the stage for an important scientific discussion, and while that could be viewed as confusing, it is better than having only one of those studies published.

To be confident in scientific results, they must be reproducible, and that included reproducibility of different scientists coming to the same or similar conclusions when using the same data.

6. OPEN DATA AND PUBLIC DOMAIN

Publications by NIH scientists are automatically in the public domain, but that is not true for other NIH products nor for NIH funded scientists outside NIH. It is especially important to make all publicly funded research data public, so that research can be scrutinized and reproduced by other scientists.

PROPOSAL #6:

All data generated by NIH grants should be in the public domain and made available to other scientists. For large projects described above, access should be immediately once the data has been collected, and quality checked. For regular investigator-initiated projects, the data should be made available at the time when the investigator publishes research using the data. All other NIH funded products, including scientific discoveries and software, should also be in the public domain.

7. INSTITUTIONAL OVERHEAD

In addition to its direct costs of personnel and equipment, successful research also depends on institutional support such as a building to work in, computing resources, a good university library, scientific discussions, and administrative support. To pay for such overhead, institutions charge NIH indirect costs as a percentage on top of the direct grant money. The percentage varies widely among different universities and research institutes. For example, the indirect rate negotiated by Harvard’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston is 79 percent, while it is only 47% at the University of Maine.

If there are two equally meritorious grant applications, American taxpayers get more value for the money if the one with the lower indirect percentage is funded. Instead, institutions that can show that their overhead costs are larger have been rewarded with a higher percentage and more money, determined by a separate bureaucratic negotiation process with each institution. Universities operating more efficiently have received less money. Those efficient institutions should instead be rewarded by letting them use overhead funds for additional research projects of their own choice.

Many grants include investigators from multiple institutions. For a portion of such grant, both the primary recipient institution and the subcontracting institutions are allowed to charge overhead at their standard rate. The total indirect on such funds can therefore be over 100 percent. It also makes the accounting more complex and time consuming.

PROPOSAL #7:

The NIH indirect rate should be identical for all domestic institutions. The appropriate level can be discussed. It could be more than 15% but it should be less than 79%. Institutions would report how much of it is used for buildings, libraries, departmental support services, internally funded research projects, scientific meetings/discussions, and university administration, with a strict upper limit on the latter. Overhead double-dipping must end, so that institutions only charge indirect costs on their own direct costs.

8. ACADEMIC FREEDOM AND OPEN SCIENTIFIC DISCOURSE

During the pandemic, former NIH director Francis Collins denoted those who disagreed with him as ‘fringe epidemiologists,’ requesting a ‘devastating published takedown,’ rather than encouraging and organizing open scientific discourse about contentious scientific topics.8 As a result, the United States ended up with one of the highest excess mortality rates during the pandemic while Sweden, which famously followed basic principles of public health, had the lowest excess mortality rate among major Western countries.9

Rather than orchestrating devastating takedowns, NIH should actively promote open scientific discussions about important health topics. Intense and passionate scientific debate should be encouraged. The scientific community cannot control what the general public writes on social media, but as scientists we should always listen to each other and engage in polite and respectful scientific discussions.

Science is universal and science needs the best talents, whoever provides it. Institutions that receive NIH research grants should promote academic freedom, open discourse, and not discriminate based on for example gender, skin color, ethnicity, religion, sexual preferences, political beliefs, disability, or health preferences.

If an institution cannot uphold these basic academic values that are fundamental for the progress of science, individual scientists should still be funded, but institutional overhead should not be provided on NIH grants.

PROPOSAL #8:

A small part of the institute overhead on grants, say 1%, could be used to enhance open scientific discourse at universities and other grant receiving institutions. Institutions that receive indirect overhead from taxpayer-funded grants should be required uphold academic freedom, with no discrimination based on gender, skin color, ethnicity, religion, sexual preferences, political beliefs, ethical convictions, disability, vaccination history, or other health status. Digressions during the pandemic should be rectified.

9. SCIENTISTS AT NIH

There are important intramural research programs conducted by in-house NIH scientists. These research groups can quickly pursue important research, as they do not have to write research grants and wait for approval by NIH review panels. In other ways, they are more restricted. For example, their research requires internal clearance before it can be submitted for publication.

PROPOSAL #9:

Scientists at NIH should have academic freedom and be entrusted to freely publish their research without clearance by superiors. A simple statement that their conclusions may not reflect official NIH views is sufficient. It is good when scientists are free to have divergent perspectives on an issue, and NIH leadership should not feel threatened by that. NIH could also expand its post-doc programs to allow more junior scientists to experience the dynamic NIH research environment for a couple of years.

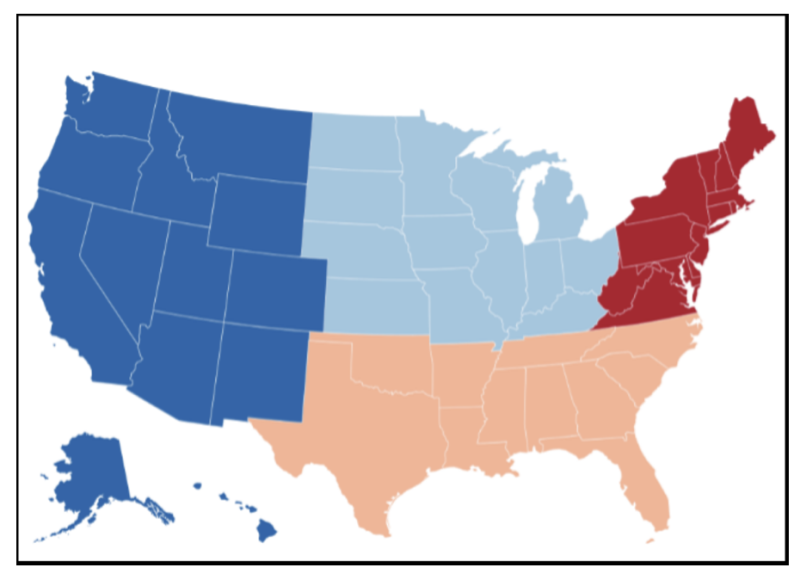

10. DECENTRALIZATION

During the Covid pandemic, much of the early important information did not come from the scientific powerhouses of the United States and Britain, but from smaller peripheral countries with high quality science, such as Iceland, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Catalonia, and Qatar. For example, they gave us some of the earliest information about Covid transmission,10 the effect of school closures,11 natural infection-acquired immunity,12 mask efficacy,13,14 and waning vaccine efficacy.15

As the director of NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), Dr. Anthony Fauci sat on the biggest pile of infectious disease research money in the world. That made infectious disease scientists cautious about opposing his public health views about the pandemic, even though Dr. Fauci is a lab scientist with limited public health expertise. One can never guarantee that another Fauci won’t rise to the top, but with multiple independent infectious disease research institutes, at least some of them will be functioning during the next pandemic even if one is led by a Dr. Faust. Even when all institute directors are excellent, there is still an advantage with variety in ideas and emphasis.

PROPOSAL #10:

For each specific disease area, create four regional NIH institutes with different directors, covering the Northeast, South, Midwest, and West respectively. This means that there for example will be four regional NIAIDs with different directors and different ideas and research priorities. Scientists would apply for grants based on where they work, with each region allocated funds in proportion to its population. Some parts of NIH, such as the National Library of Medicine, the Clinical Center, and the Center for Scientific Review, should remain centralized, serving the whole country. To avoid too many institutes, geographical-based decentralization could be combined with the merging of institutes for related areas, such as the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and the National Institute of Mental Health.

11. RESEARCH VERSUS POLICY

NIH is a research institute entrusted to fund and conduct medical and public health research. It is not a medical or public health policy institute. If NIH or its institutes argue for specific health policies, it can be hard for NIH-funded scientists to objectively present research that contradicts policies advocated by NIH leaders.

During the pandemic, NIH should have focused on quickly launching the necessary research studies to understand transmission and natural infection-acquired immunity, developing and evaluating therapeutics, evaluating vaccine efficacy and safety, and studying potential preventive measures such as masking and social distancing. It failed on many of those fronts.

Instead, NIH made health policy decisions and recommendations without scientific evidence, as both the NIH and NIAID directors became leading proponents on the misguided pandemic strategy with school closures and other lockdown measures. Public health policy is the responsibility of state health departments and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, not the NIH.

PROPOSAL #11:

NIH should focus exclusively on its research mission. To maintain credibility as an objective world-class medical research institute, NIH should avoid medical and public health policy, with the sole exception of policies concerning its own research portfolio. Research requires an open mind to consider multiple options and any results, and it must embrace evidence-based medicine no matter what the research results are.

12. A NATIONAL COVID COMMISSION

The public confidence in federal health agencies took a beating during the Covid pandemic. There have been pandemic evaluations by a grand jury in Florida,16 by the New Hampshire legislature,17 and by the US House of Representatives,18 but nothing by the scientific or public health communities. That is necessary to restore the integrity of medicine and public health, so that we will again deserve the trust and confidence of the public.

PROPOSAL #12:

NIH should establish a Covid Commission to conduct an evidence-based examination of different aspects of our pandemic response. It may cover the ten topics outlined by the Norfolk Group: protecting high-risk Americans, infection-acquired immunity, school closures, collateral lockdown harms, public health data and risk communication, epidemiologic modeling, therapeutics and clinical interventions, vaccines, testing and contact tracing, and masks.19 To assist such a Commission, NIH needs to be transparent with its own role during the pandemic, releasing NIH and NIAID correspondence about the pandemic, including redacted parts of past FOIA requests.

All scientists should be in favor of a national Covid Commission. Not only to seek the truth and avoid the same mistakes in the future, but also for purely egotistical reasons. Without broad public confidence in the scientific community, the public support and funding for NIH will gradually decline.

CONCLUSION

Not only NIH but the whole scientific community is at a crossroad. It is now evident to most of the public that medical and public health leaders failed us during the pandemic, abandoning evidence-based medicine and the basic principles of public health. One option for scientists is to try to forget the pandemic, ignore the mishaps, and then complain in vain as the public trust and science funding decline. The other option is to acknowledge the mistakes and reform both NIH and other scientific institutions to reestablish the integrity of the scientific enterprise, with a gradual restoration of public trust and continued resources for important medical and public health research.

REFERENCES

- Prasad V. Randomize NIH grant giving. Sensible Medicine, February 2, 2025.

- Eisen M. Twitter post x.com/mbeisen/status/1863766472524521611, December 2, 2024.

- Betagnolli M. NIH issues new policy to speed access to agency-funded research results, National Institutes of Health, December 17, 2024.

- Kulldorff M. The Rise and Fall of Scientific Journals and a Way Forward. Journal of the Academy of Public Health, 1: 2025.

- Demasi M. Cochrane – A sinking ship? British Medical Journal, EBM Spotlight, September 16, 2018.

- Andersson C, Johnson AD, Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vasan RS. 70-year legacy of the Framingham Heart Study. Nature Reviews Cardiology 16:687–698, 2019.

- Gohagan JK, Prorok PC, Hayes RB, Kramer BS, PLCO Project Team. The prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening trial of the National Cancer Institute: history, organization, and status. Controlled Clinical Trials, 21:251S-272S, 2000.

- Magness P and Harrigan JR. Fauci, Emails, and Some Alleged Science, The Daily Economy, December 19, 2021.

- Norberg J. Sweden During the Pandemic. Cato Institute, Policy Analysis No. 959, August 29, 2023.

- Gudbjartsson DF, Helgason A, Jonsson H, Magnusson OT, Melsted P, Norddahl GL, Saemundsdottir J, Sigurdsson A, Sulem P, Agustsdottir AB, Eiriksdottir B. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the Icelandic population. New England Journal of Medicine. 382:2302-215, 2020.

- Public Health Agency of Sweden and Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, Covid-19 in schoolchildren: A comparison between Finland and Sweden. June 14, 2020.

- Abu-Raddad LJ, Chemaitelly H, Malek JA, Ahmed AA, Mohamoud YA, Younuskunju S, Ayoub HH, Al Kanaani Z, Al Khal A, Al Kuwari E, Butt AA, Coyle P, Jeremijenko A, Kaleeckal AH, Latif AN, Shaik RM, Rahim HFA, Yassine HM, Al Kuwari MG, Al Romaihi HE, Al Thani SM, Bertollini R. Assessment of the risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection in an intense re-exposure setting. medRxiv, September 29, 2020.

- Bundgaard H, Bundgaard JS, Raaschou-Pedersen DE, von Buchwald C, Todsen T, Norsk JB, Pries-Heje MM, Vissing CR, Nielsen PB, Winsløw UC, Fogh K. Effectiveness of adding a mask recommendation to other public health measures to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection in Danish mask wearers: a randomized controlled trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 174:335-343, 2021.

- Coma E, Català M, Méndez-Boo L, Alonso S, Hermosilla E, Alvarez-Lacalle E, Pino D, Medina M, Asso L, Gatell A, Bassat Q. Unravelling the role of the mandatory use of face covering masks for the control of SARS-CoV-2 in schools: a quasi-experimental study nested in a population-based cohort in Catalonia (Spain). SSRN, March 7, 2022.

- Nordström P, Ballin M, Nordström A. Risk of infection, hospitalization, and death up to 9 months after a second dose of COVID-19 vaccine: a retrospective, total population cohort study in Sweden. SSRN, October 25, 2021.

- State of Florida, Final Report of the Twenty-Second Statewide Grand Jury. November 22, 2024.

- State of New Hampshire, Reports of the Special Committee on COVID Response Efficacy, November 18, 2024.

- United States House of Representatives, Final Report of the Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic Committee on Oversight and Accountability, After Action Review of the Covid-19 Pandemic, The Lessons Learned and a Path Forward, December 4, 2024.

- Bhattacharya J, Bienen L, Duriseti R, Høeg TB, Kulldorff M, Makary M, Smelkinson M, Templeton S. Questions for a Covid-19 Commission, Norfolk Group (www.norfolkgroup.org), January 2023.

Republished from Journal of the Academy of Public Health

A Blueprint for NIH Reform

by Martin Kulldorff at Brownstone Institute – Daily Economics, Policy, Public Health, Society

Author: Martin Kulldorff

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://brownstone.org and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.