Today I’m extremely happy to be bringing you the latest from my friend Lyn Alden.

Lyn’s background bridges the fields of engineering and finance. She holds a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering and a master’s degree in engineering management, specializing in engineering economics, systems engineering, and financial modeling. Her early career included roles as an electrical engineer and later an engineering lead at the Federal Aviation Administration’s William J. Hughes Technical Center.

Alden has been a passionate investor for years. From 2010 to 2015, she ran her first investing website as a part-time venture, eventually selling it to a larger publishing company. In late 2016, she founded Lyn Alden Investment Strategy, a research firm that grew significantly, leading her to leave engineering management in 2021 to focus on finance full-time.

Now an independent analyst, Alden aims to deliver institutional-level research in clear, accessible language for both professional and retail investors. She also serves as an independent director on the board of Swan.com and is a general partner at the venture capital firm Ego Death Capital. In 2023, she published the best-selling book Broken Money (congrats on more than 100,000 copies sold, Lyn!) exploring the history, present, and future of money through a technological lens.

Lyn is an investor I always read and always love to hear from, so I was grateful she gave me permission to share this month’s research with my subscribers. I’m sure you’ll find it as valuable as I do.

June 2025

This newsletter issue analyzes three common misconceptions about the US federal debt and deficits.

The ongoing nature of the deficits has several investment implications, but along the way it’s important to not get distracted by things that don’t add up.

Fiscal Debt and Deficits 101

Before I jump into the misconceptions, it’s useful to quickly remind what the debt and deficits are, specifically.

-In most years, the US federal government spends more than it receives in tax revenue. That difference is the annual deficit. We can see the deficit over time here, both in nominal terms and as a percentage of GDP:

-As the US federal government runs deficits over years and decades, they add up to the total outstanding debt. That’s the stock of debt that the US federal government owes to lenders, which they pay interest on. When some of their bonds mature, they issue new ones to help pay back the old ones.

A couple of weeks ago at a conference in Las Vegas, I gave a keynote talk about the US fiscal debt situation (available here), which serves as an easy 20-minute summary of the situation.

My view for a while, as outlined in that talk and for years now, is that US fiscal deficits will be quite large for the foreseeable future. I’ve discussed that in numerous pieces and formats, but my September 2024 newsletter was the most detailed breakdown of it, along with Sam Callahan’s January 2025 report.

Misconception 1) We Owe it to Ourselves

A common phrase, popularized by Paul Krugman and others, is that “we owe the debt to ourselves”. Proponents of Modern Monetary Theory often make similar statements, e.g. saying that the cumulative debt outstanding is mainly just a tally of surpluses that have been given to the private sector.

The unsaid implications from this is that the debt isn’t a big deal. Another potential implication is that maybe we could selectively default on portions of it, since it’s just “owed to ourselves”. Let’s examine those two parts separately.

Who It’s Owed To

The federal government owes money to US Treasury security holders. That includes entities in foreign countries, includes US institutions, and includes US individuals. And of course, those entities have specific amounts of treasuries. The government of Japan, for example, is owed a lot more dollars than me, even though we both own treasuries.

If you, me, and eight other people go out to dinner in a big 10-person group, we owe a bill at the end. If we all ate different amounts of food, then we likely don’t have the same liabilities here. The cost generally has to be split in fair ways.

Now in practice for that dinner example, it’s not a big deal because dinner groups are usually friendly with each other, and people are willing to graciously cover others in that group. But in a country of 340 million people living within 130 million different households, it’s no small matter. If you divide $36 trillion in federal debt by 130 million households, you get $277,000 per household in federal debt debt. Do you consider that your household’s fair share? If not, how do we tally that up?

Put another way, if you have $1 million worth of treasuries in your retirement account, and I have $100,000 worth of treasuries in my retirement account, yet both of us are taxpayers, then while in some sense “we owe it to ourselves”, it’s certainly not in equal measure.

In other words, the numbers and proportions do matter. Bondholders expect (often incorrectly) that their bonds will retain purchasing power. Taxpayers expect (again often incorrectly) their government to maintain sound fundamentals in its currency and taxing and spending. That seems obvious, but sometimes needs to be clarified anyway.

We have a shared ledger, and we have a division of powers about how that ledger is managed. Those rules can change over time, but the overall reliability of that ledger is why the world uses it.

Can We Selectively Default?

Individuals, businesses, and countries that owe debt denominated in units that they cannot print (e.g. gold ounces or someone else’s currency) can indeed default if they lack sufficient cashflows or assets to cover their liabilities. However, developed country governments, whose debt is usually denominated in their own currency that they can print, rarely default nominally. The far easier path for them is to print money and debase the debt away relative to the country’s economic output and scarcer assets.

Myself and many others would argue that a major currency devaluation is a type of default. In that sense, the US government defaulted on bondholders in the 1930s by devaluating the dollar vs gold, and then again in the 1970s by decoupling the dollar from gold entirely. The 2020-2021 period was also a type of default, in the sense that the broad money supply increased by 40% in a rapid period of time, and bondholders had their worst bear market in over a century, with greatly decreased purchasing power relative to virtually every other asset.

But technically, a country could also default nominally, even if it doesn’t have to. Rather than spreading the pain out with debasement to all bondholders and currency holders, they could instead just default on unfriendly entities, or entities that are in a position to withstand it, thus sparing currency holders broadly, and the bondholders that were not defaulted on. That’s a serious possibility worth considering in such a geopolitically strained world.

And so the real question is: are there certain entities for which defaulting has limited consequences?

There are some entities that have very large and obvious consequences if they are defaulted on:

-If the government defaults on retirees, or the asset managers holding treasuries on behalf of retirees, then it would impair their ability to support themselves after a lifetime of work, and we’d see seniors in the streets in protest.

-If the government defaults on insurance companies, then it impairs their ability to pay out insurance claims, thus hurting American citizens in a similarly bad way.

-If the government defaults on banks, it’ll render them insolvent, and consumer bank deposits won’t be fully backed by assets.

And of course, most of those entities (the ones that survive) would refuse to ever buy a treasury again.

That leaves some lower-hanging fruit. Are there some entities that the government could default on, which might hurt less and not be as existential as those options? The possibilities are generally foreigners and the Fed, so let’s analyze those separately.

Analysis: Defaulting on Foreigners

Foreign entities hold about $9 trillion in US treasuries currently, out of $36 trillion in debt outstanding. So, about a quarter of it.

And of that $9 trillion, about $4 trillion is held by sovereign entities and $5 trillion is held by foreign private entities.

The prospect for defaulting on specific foreign entities certainly jumped higher in recent years. In the past, the US froze sovereign assets of Iran and Afghanistan, but those were considered small and extreme enough to not count as any sort of “real” default. However, in 2022 after Russia invaded Ukraine, the US and its allies in Europe and elsewhere froze Russian reserves totaling over $300 billion. A freeze isn’t quite the same as a default (it depends on the ultimate fate of the assets), but it’s pretty close to one.

Since that time, foreign central banks have become pretty big gold buyers. Gold represents an asset that they can custody themselves, and thus is protected against default and confiscation, while also being hard to debase.

The vast majority of foreign-held US debt is held within friendly countries and allies. These are countries like Japan, the United Kingdom, Canada, and so forth. Some of them like Cayman Islands, Luxembourg, Belgium, and Ireland are haven areas where plenty of institutions set up shop and hold Treasuries. So, some of these foreign holders are actually US-based entities that are incorporated in those types of places.

China has less than $800 billion in treasuries now, which is only about 5 months worth of US deficit spending. They’re near the top of the potential “selective default” risk spectrum, and they’re aware of it.

If the US were to default at a large scale on these types of entities, it would greatly impair the ability for the US to convince foreign entities to hold their treasuries for a long time. The freezing of Russian reserves already sent a signal that countries responded to, but in that instance they had the cover of a literal invasion. Defaulting on debt held by non-aggressive nations would be seen as a clear and obvious default.

So, this isn’t a particularly viable option overall, although there are certain pockets where it’s not out of the realm of possibility.

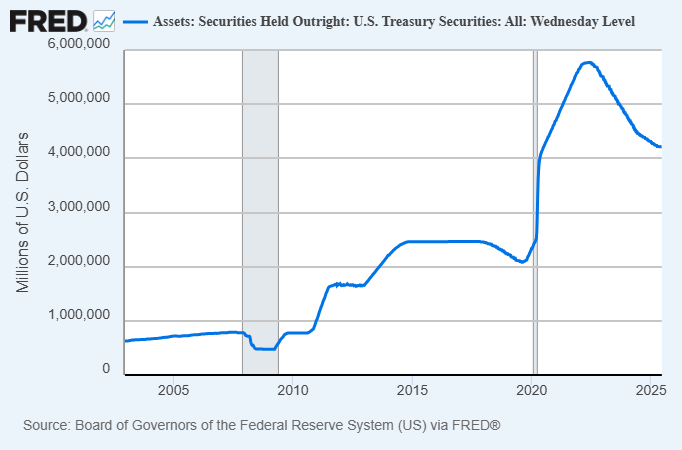

Analysis: Defaulting on the Fed

The other option is that the Treasury could default on the treasuries that the US Federal Reserve holds. That’s a little over $4 trillion currently. After all, that’s the closest version of “we owe it to ourselves” right?

There are major problems with that, too.

The Fed, like any bank, has assets and liabilities. Their primary liabilities are 1) physical currency and 2) bank reserves owed to commercial banks. Their primary assets are 1) treasuries and 2) mortgage-backed securities. Their assets pay them interest, and they pay interest on bank reserves in order to set an interest rate floor and slow down banks’ incentive to lend and create more broad money.

Currently, the Fed is sitting on major unrealized losses (hundreds of billions) and is paying out more interest than they receive each week. If they were a normal bank, they’d experience a bank run and be shut down. But because they’re the central bank, nobody can do a bank run on them, so they can operate at a loss for a very long time. They’ve racked up over $230 billion in cumulative net interest losses over the past three years:

If the Treasury were to totally default on the Fed, it would render them massively insolvent on a realized basis (they’d have trillions more in liabilities than in assets), but as the central bank they’d still be able to avoid a bank run. Their weekly net interest losses would be even greater, because they’d have lost most of their interest income at that point (since they’d only have their mortgage backed securities).

The main problem with this approach is that it would impair any notion of central bank independence. The central bank is supposed to be mostly separate from the executive branch, and so for example the President can’t cut interest rates before an election and raise interest rates afterward, and do shenanigans like that. The President and Congress put the Fed’s board of governors in place with long terms of service, but then from there the Fed has its own budget, is generally supposed to run profitably, and support itself. A defaulted-on Fed is an unprofitable Fed, and with major negative equity. That’s a Fed that is no longer independent, and doesn’t even have the illusion of being independent.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Quoth the Raven

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://quoththeraven.substack.com feed and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.