When I give speeches about Trump’s protectionism, the most-common question I get is about the impact on jobs (it’s a net job destroyer).

In the past month or two, however, I’m getting more questions about protectionism and inflation. Especially from people who seem to think that low levels of inflation in America are evidence that economists have been wrong to criticize Trump.

So here are some visuals to help understand the link (or lack thereof) between inflation and protectionism.

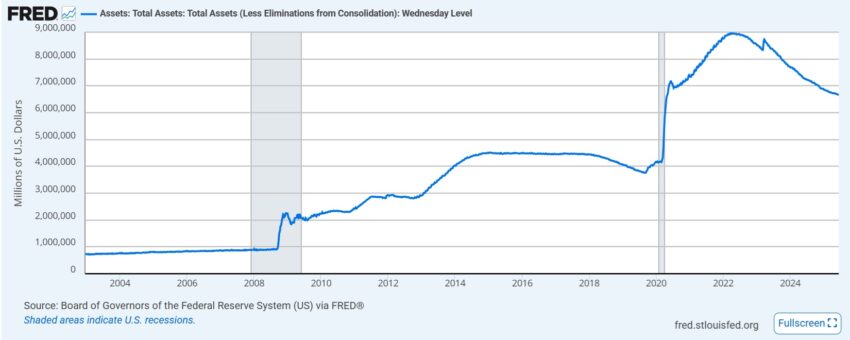

We’ll start with this look at the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet, which it the first thing I look at when investigating if monetary policy is too loose.

As you can see, the Fed created lots of additional money in 2020 and 2021, so it’s no surprise that the country suffered from big increases in the overall price level in 2022.

But notice that the Fed has been soaking up some of that excess liquidity for the past few years.

And since the Fed has not been following an inflationary policy in recent years, it should be no surprise that the overall price level is largely stable.

The moral of the story is that Milton Friedman was right. Inflation is always a monetary phenomenon.

Indeed, the main message of today’s column is that protectionism is not inflationary. Assuming, of course, that the Fed doesn’t try to facilitate and accommodate the protectionism by creating excess money.

Trade barriers are bad for prosperity for other reasons.

After pointing to the overall price level, the people who want to defend Trump’s protectionism then sometimes call attention to the prices of certain goods.

I get questions such as “Why haven’t the prices for X and Y increased by 20 percent after the 20 percent tariff?”

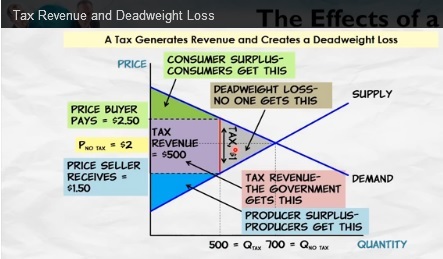

The answer can be seen in supply-and-demand curves. The actual impact of a tariff (or any other kind of tax) is completely dependent on market conditions.

Maybe a price will go up 5 percent. Maybe it will go up 15 percent.

What really matters is the level of deadweight loss, however, at least if the goal is to have more prosperity.

But if you want evidence that trade taxes can effect specific prices, this tweet from Scott Lincicome should be very compelling.

And this tweet from Derek Guy shows how various companies are responding to the higher trade taxes.

A substantial share hope to shift all the taxes on to consumers.

What actually happens will depend on economic conditions, including factors such as consumer price sensitivity and whether imports are a big or small share of that market.

As I already noted, it’s the deadweight loss (the decline in overall output) that most worries economists, not whether protectionism increases the overall price level.

That being said, protectionism can cause significant relative prices changes. Some goods become more expensive and some goods become cheaper as the economy adjusts to the distortions caused by protectionism.

In the absence of bad monetary policy, however, there should not be any meaningful increase in average prices.

P.S. Since I just raised the issue of whether imports are a big or small share of the market, here is a chart showing imports as a share of overall economic output in the United States.

It looks like trade fluctuates a lot, but keep in mind that the vertical axis only goes from 13 percent to 18 percent.

What you actually see is that imports this century have averaged about 15 percent of GDP, sometimes a percentage point or two higher, sometimes a percentage point or two lower.

Interestingly, because the United States has a massive economy and a huge internal market, imports play a small role, at least by global standards.

Imports currently are about 14 percent of GDP, which is much lower than other major nations such as Germany (39.4 percent of GDP), Japan (23.4 percent of GDP), and even China (17.6 percent of GDP).

Why am I citing this data? Because if you look at the jurisdictions with the most imports as a share of GDP, you’ll find some of the world’s richest and most successful economies: Singapore (136.9 percent of GDP), San Marino (173 percent of GDP), Luxembourg (181 percent of GDP), and Hong Kong (176 percent of GDP).

The first point to understand is that small rich nations will have a huge amount of trade (and be very free-trade oriented) because they understand that imports and exports are both good for prosperity. The second point to understand is that Trump is very foolish to think that imports are a sign of economic weakness.

P.P.S. I wrote last month about a special scenario where protectionism might lead to an increase in the overall price level.

…protectionist trade policy could lead to higher overall prices over time because of falling output. We normally think of prices rising because of bad monetary policy – i.e., the M rising in the MV=PO equation, causing the P to then increase (where M is money, V is velocity, the P is prices and the O is output). However if protectionism leads to falling O because of a less-dynamic economy, then the P will increase. Economists sometimes use the colloquial phrase that “inflation is too much money chasing too few goods.” In most cases, the “too much money” is the problem. But it’s also possible that “too few goods” can be the driving force.

The bottom line is that the Federal Reserve has a long track record of mistakes. In this special case, though, it would not be the Fed’s fault.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Dan Mitchell

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://freedomandprosperity.org and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.