By

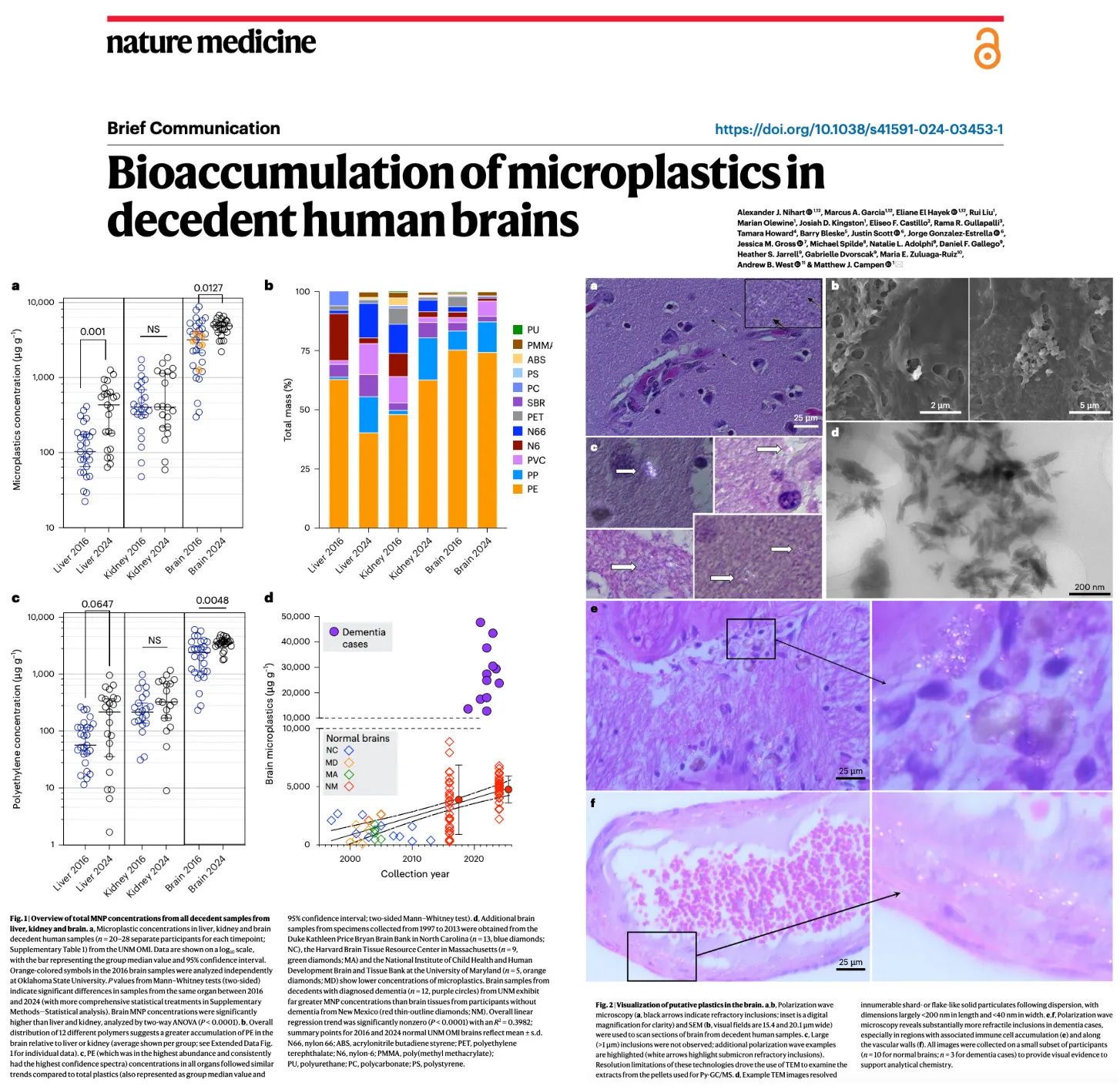

Concerningly, Nihart et al found increasing brain accumulation of microplastics over time, with fivefold higher levels in dementia patients. Median brain microplastic concentration increased from 3,345 µg/g in 2016 to 4,917 µg/g in 2024:

A recent systematic review by Chartres et al found possible links between microplastics, cancer, and harm to the reproductive, digestive, and respiratory systems:

Now, a breakthrough study published in Brain Medicine by Bornstein et al offers the first clinical evidence that extracorporeal therapeutic apheresis (a clinical blood-filtration technique) may help remove these toxic particles from the human body:

Key Findings:

-

In this study, 21 patients with chronic fatigue conditions (including long COVID) underwent a treatment called extracorporeal therapeutic apheresis—a medical procedure that filters the blood outside the body to remove harmful substances.

-

The process works in two steps:

-

Blood is drawn from the patient and passed through a membrane that separates the plasma (the liquid part of blood) from the blood cells.

-

That plasma is then run through ultrafine filters—small enough to catch particles as tiny as nanoplastics—to remove unwanted materials.

-

-

After treatment, researchers analyzed the eluate (the waste fluid collected from the filter) and found microplastic-like particles, including polyamide 6 (nylon) and polyurethane, using a method called ATR-FT-IR spectroscopy, which identifies chemical substances by how they absorb infrared light.

-

These plastic particles were not found in any clean filter control tests, strongly suggesting they came from the patients’ blood.

-

Although the study didn’t test blood samples before and after treatment to measure exactly how much was removed, the detection of these plastics in the filtered waste provides the first clinical evidence that this kind of blood filtration can physically remove microplastics from the human body.

Microplastic exposure is inescapable in modern environments. Until now, no validated method existed to remove these particles from the human body. This study offers the first clinical proof-of-concept that therapeutic apheresis can extract microplastic-like particles from circulation. The authors call for larger, quantitative studies to measure blood microplastic levels before and after treatment, optimize filtration systems, and investigate potential links between particle removal and symptom relief in chronic illness.

Epidemiologist and Foundation Administrator, McCullough Foundation

www.mcculloughfnd.org

Please consider following both the McCullough Foundation and my personal account on X (formerly Twitter) for further content.

Bornstein SR, Gruber T, Katsere D, et al. Therapeutic apheresis: A promising method to remove microplastics?. Brain Med. 2025;1(3):52-53. doi:10.61373/bm025l.0056