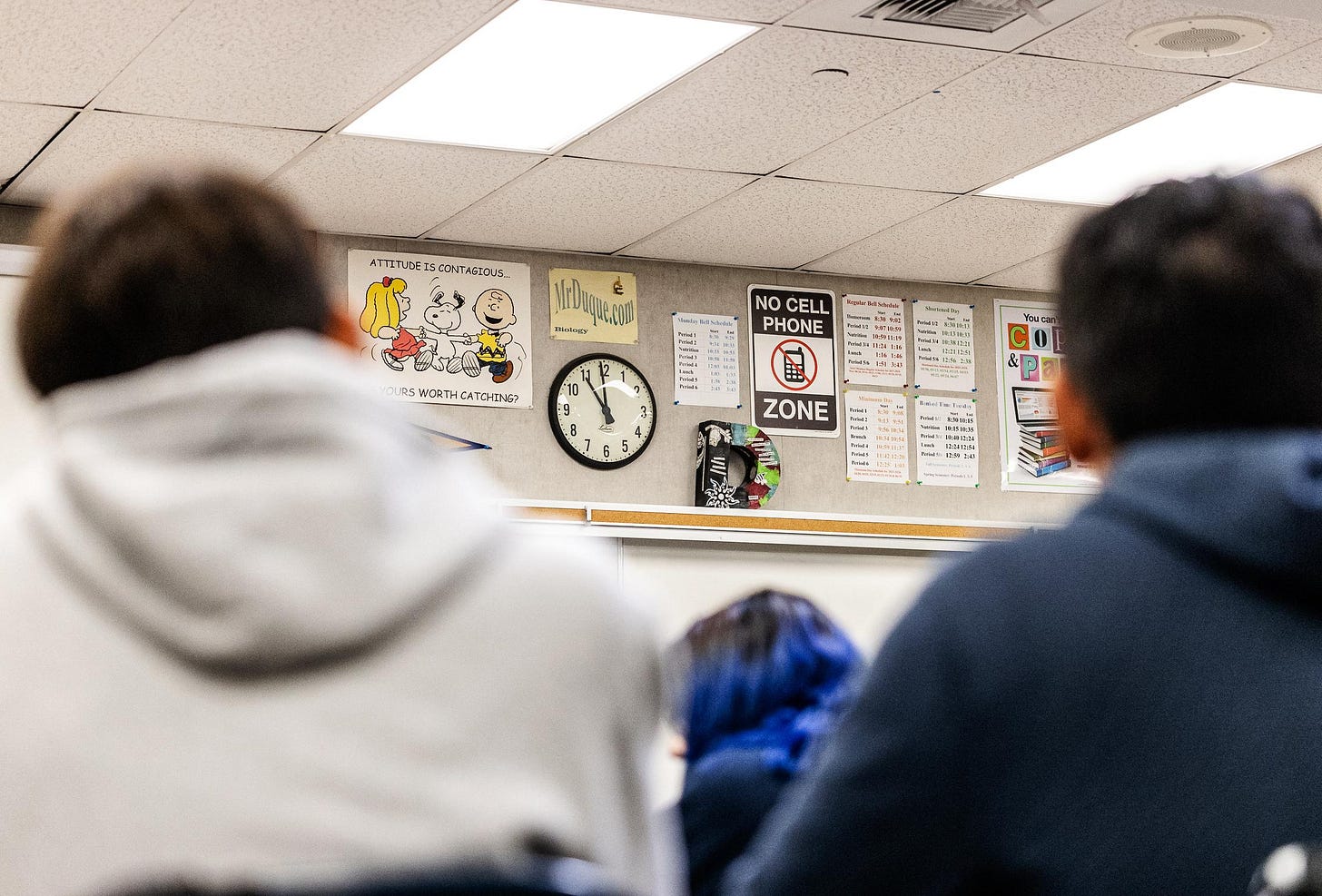

(The Epoch Times)—As tens of millions of children head back to school, parents and teachers are grappling with questions about how much artificial intelligence (AI) is too much.

The education system will be one of the primary laboratories for the global AI experiment, according to author Joe Allen.

“Schools—to the extent that they either mandate or encourage the adoption of AI—are going to be massive petri dishes in which we’ll find out whether it’s better to maintain traditional cultural norms, or if we turn every child possible into a cyborg,” he told The Epoch Times.

No one knows what the long-term effects will be, said Allen, who authored “Dark Aeon: Transhumanism and the War Against Humanity.”

In the same way that popular technology, such as TV and portable transistor radios, broadcast the music and message of subculture movements that influenced a generation of children to break away from their parents’ cultural norms during the ’60s, he believes AI could also impact “a generation of children who are acclimated to interacting with machines, basically as if they were people.”

As tens of millions of children head back to school, parents and teachers are grappling with questions about how much artificial intelligence (AI) is too much.

The education system will be one of the primary laboratories for the global AI experiment, according to author Joe Allen.

“Schools—to the extent that they either mandate or encourage the adoption of AI—are going to be massive petri dishes in which we’ll find out whether it’s better to maintain traditional cultural norms, or if we turn every child possible into a cyborg,” he told The Epoch Times.

No one knows what the long-term effects will be, said Allen, who authored “Dark Aeon: Transhumanism and the War Against Humanity.”

In the same way that popular technology, such as TV and portable transistor radios, broadcast the music and message of subculture movements that influenced a generation of children to break away from their parents’ cultural norms during the ’60s, he believes AI could also impact “a generation of children who are acclimated to interacting with machines, basically as if they were people.”

A majority of parents in several surveys have expressed concern about the effects of AI use on their children.

A study by DoodleLearning last year found that roughly 80 percent of 1,000 parents with school-aged children in school were worried about the impact of AI on education. Parents surveyed were also worried about privacy, data security, and plagiarism.

The Department of Education in July encouraged schools to teach children how to use AI responsibly and to use it to “personalize learning” for “students at all levels.”

‘Your Brain on ChatGPT’

Shannon Kroner, a clinical psychologist, educational therapist for more than 20 years and children’s book author, believes that AI affects critical thinking and “dehumanizes both the teacher and the child.”

Kroner, who has taught high school biology and college humanities courses, said AI reduces education from healthy learning based on teacher-student relationships to a cold transaction.

“AI creates an intellectual laziness in both the teacher and the student, and … an erosion of curiosity, stunted cognitive development and reduced problem solving. It weakens logic and reasoning,” she told The Epoch Times.

“The students aren’t going to need to do the research and dig through the studies needed in order to defend their perspective on whatever it is that they need to prove,” she said.

Educators are consulting AI more frequently to develop lesson plans because it makes their jobs easier, but it will eventually disempower them in their roles as teachers as students rely more and more “on what a robot says.”

“We’re really going to lose that teacher-student connection,” she said. “The more it becomes natural to use AI, students will just turn to AI for answers, and it won’t matter what the discussion is between the teacher and the student. The discussion will probably end up being obsolete. There won’t be a discussion.”

Allen and Kroner are both concerned about the erosion of critical thinking skills in the classroom.

A recent MIT study, “Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt When Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task,” looked at whether AI harms critical thinking abilities.

The study correlated cognitive and neurological data from 54 students, ranging in age from 18 to 39. It used electroencephalography (EEG) to record the brain activity. The students were divided into three groups—one using OpenAI’s ChatGPT, another using Google’s search engine, and the third using nothing but their brains—and were tasked with writing several essays.

The study found that ChatGPT users, or large language model AI users, had the lowest brain engagement and often resorted to cut-and-paste answers.

Over four months, large language model users “consistently underperformed” at neural, linguistic, and behavioral levels. These results raise concerns about the long-term educational implications of LLM [large language model] reliance and underscore the need for deeper inquiry into AI’s role in learning,” the study concluded.

The group using AI was “completely bored” and showed lower memory recall, with less brain activity, especially in the hippocampus where memories are formed, Allen said.

Essentially, he said, the study confirms that “AI makes people stupider. If you rely on a machine to do your thinking for you, you won’t think as well.”

Mental Health Concerns, Artificial Friends

AI’s effects on humanity likely won’t be known for years, much like the long-term effects of the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Allen said.

The pandemic lockdowns, work from home, and virtual learning push that resulted solidified the trend away from in-person interaction.

Extensive use of social media, especially during the pandemic, has been widely identified in studies as a factor in mental health problems for youth. Kroner is worried that adding AI to the mix could worsen the problem.

AI companies are promoting robotic artificial friends and chatbots as companions for children who were isolated from their real friends during the pandemic, and now people are turning to AI for therapy, she said.

The technological move toward humanoid robots and encouraging artificial friends for children raises other questions such as whether such AI products can alleviate loneliness in shy or socially awkward children, or if it will further alienate and isolate them from other children and healthy physical activities such as playing outdoors and sports.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), prescriptions of antidepressants to adolescents and young adults were already rising before COVID-19, but from March 2020 onwards, they surged by an additional 60 percent.

Kroner fears AI will destroy the innocence of childhood, including through the sexualization of chatbots, including X-based chatbot character, “Ani.”

AI systems also come with risks to privacy for children entering personal data into these systems, Kroner said.

“Who’s collecting all the data and can that data eventually be exploited?” she asked. “Who is holding onto that data?”

While the phrase “garbage in, garbage out” still applies in computing to some extent, AI is vastly different, he said. In classical computing,“garbage in, garbage out” meant that “if you threw a bunch of garbage into a rules-based program, you could kind of predict the garbage that would come out from the garbage that came in.”

But you can throw “garbage and gold” into large language models and they can select the gold from the garbage. Unlike basic search engines that serve as simple database lookup tools, AI has a mind of its own in the sense it can navigate its own path through data within bounds as users ask questions, allowing it to uncover a lot of useful information that otherwise may have been buried, Allen said.

In some ways, AI functions like a human brain with a degree of freedom and randomness, but it does so in a “very alien way,” he said.

“Just the hallucination rates alone should be enough to alarm parents that it’s not going to be the super genius that people like Sam Altman are promising,” Allen said.

AI is prone to confabulation known as “hallucinations” that present false or misleading information not based on perceptual experiences, and it does so in a convincing manner.

In company tests, OpenAI’s latest 03 and 04-mini models hallucinated 51 percent and 79 percent of the time. And in a 2024 study evaluating the use of AI in the legal profession, hallucination rates ranged up to 88 percent.

Allen pointed to an example of ChatGPT’s latest 4.5 version abandoning guardrails meant to prevent certain discussions and instructing users how to conduct sacrifices to Molech, an ancient deity historically associated with child sacrifice.

There have been many other cases of people breaking through AI guardrails. In one recent example, in early July the Grok chatbot unexpectedly generated and spread a series of anti-Semitic posts.

“Inherent in the technology itself is an element of randomness. The non-deterministic nature of the system means that beneath those guardrails is turning a kind of id, and the guardrails function as a kind of super ego,” Allen said. “It doesn’t take a skilled user to get past a lot of those guardrails. You just need a few simple tricks.”

While the phrase “garbage in, garbage out” still applies in computing to some extent, AI is vastly different, he said. In classical computing,“garbage in, garbage out” meant that “if you threw a bunch of garbage into a rules-based program, you could kind of predict the garbage that would come out from the garbage that came in.”

But you can throw “garbage and gold” into large language models and they can select the gold from the garbage. Unlike basic search engines that serve as simple database lookup tools, AI has a mind of its own in the sense it can navigate its own path through data within bounds as users ask questions, allowing it to uncover a lot of useful information that otherwise may have been buried, Allen said.

In some ways, AI functions like a human brain with a degree of freedom and randomness, but it does so in a “very alien way.”

Protections for Kids

As long as governments, schools, and companies are willing to experiment with AI technologies with no real knowledge of what the outcomes will be, there is good reason to be skeptical of AI in the classroom, Allen said.

Some teachers are advocating for the return of oral exams, Blue Book tests, or students using word processors with limited internet access, Allen said. “At this early stage of the AI experiment, that’s going to be a net positive for those who do.”

He said it is possible for schools to create sanitized, academic-only AI systems.

“That’s going to be the norm going forward,” Allen said. “I wouldn’t necessarily worry about your Educational AI going off the rails and giving you passages from the Marquis de Sade.”

Allen says that there are three levels of resistance when it comes to protecting children and their critical thinking abilities: personal choice, institutional policies, and political or legal action.

At the personal choice level, parents living in America and other “free-ish societies” will be faced with the question of how to raise their children, he said.

“Parents have the choice to subject their children to this experiment or not to put kids into schools that are going full-digital or even hybrid,” he said.

At the institutional level, schools can choose whether to fully adopt AI or implement some type of partial or hybrid system, Allen said.

“Those will be critical decisions going forward,” he said. “This is an experiment, so these are going to be basically control groups,” he said.

So far, the prospect of restricting AI in American classrooms through the political and legal systems “is not looking very hopeful” beyond the state level, he said, but resistance to AI is building among coordinated parent groups in the United States and other countries.

Australia, for example, seeks to build massive data centers and open up data from Australians for use in training AI, but its policies to restrict smartphones in schools and require age verification for social media are “directionally correct,” Allen said.

“You actually have whole countries such as Australia which are doing everything possible to restrict the digital exposure on young children—everything from banning cellphones in schools to raising kids completely digital free,” he said. “So the control group is healthy.”

Kroner speculates AI will cause some children to further reject the authority of teachers and parents. She encourages parents to give real-world examples when children raise questions.

“The children can listen and give feedback and kind of take the AI out of it,” Kroner said, stressing that more human interaction and conversation are what’s missing in today’s world—not “canned responses at our fingertips.”

There is also the possibility that children trained to look at AI systems as superior teachers—especially in places where good human teachers are sparse—could outperform those who don’t use AI, Allen said.

“And, some of that is due to the fact that digital culture is so predominant that to adapt means that you are basically adapting to ever evolving norms that are pushed from the top down to the population,” he said.

“So it’s not like some natural evolution. It’s not Darwinian in the original sense, but it is an open question what the outcomes are going to be. We just simply don’t know. It’s an experiment.”

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Brad Jones

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://americafirstreport.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.