By Nicolas Cachanosky, American Institute For Economic Research

The tension between President Donald Trump and Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has reignited, following the Fed’s recent decision to hold interest rates steady. President Trump stated again that he might consider firing Powell, something he had previously ruled out. With unemployment still low and output not yet showing signs of contraction, the Fed has judged that the current policy stance is appropriate. Inflation, while lower than its peak, remains above target, leaving little room for interest rate cuts without risking renewed price pressures. Yet Trump prefers a lower interest rate, a policy that might, in the short run, counteract his policy on tariffs.

Trump’s push for lower interest rates creates economic and institutional problems. The first is macroeconomic. By lowering rates in the face of still-stubborn inflation, the Fed risks undoing the fragile progress made since the post-pandemic surge in prices. While lower rates could offer some short-term relief from the economic drag caused by trade tensions and the recent spike in tariffs — many of Trump’s own making — they would do so at the risk of future inflationary pressure. That’s a dangerous trade-off. Monetary easing in a context of persistent inflation is more likely to produce stagflation than sustainable growth.

The second problem is institutional, which is arguably more damaging in the long run. Political interference in monetary policy compromises the independence and credibility of the central bank. The Fed’s legitimacy rests on its ability to act according to economic data, not political pressure. If monetary policymakers can be cajoled into taking actions that align with electoral timelines or partisan agendas, the public will likely expect higher inflation. That would put the Fed in a difficult position: deliver the higher inflation expected by the public or risk a recession.

Two historical precedents underscore the importance of central bank independence in very different ways. Fed Chair Arthur Burns gave in to President Nixon’s pressure campaign: he lowered interest rates ahead of the 1972 election, when doing so was unwarranted by the economic data, contributing to the high inflation of the 1970s. Fed Chair Paul Volcker refused to give in to pressure from President Reagan, who wanted the Fed chair to commit to not raise rates ahead of the 1984 election. Volcker was not planning to raise rates any further at the time, but refused to commit nonetheless. Volcker’s approach helped restore price stability and solidified the Fed’s reputation for independence. That legacy is now at risk.

President Trump’s calls for the Fed to cut rates risks undermining the institution, regardless of how the Fed responds. If the Fed were to cut rates today, the public might view the decision as a capitulation to political demands. If the Fed refuses to cut rates, as it has done since December 2024, the public might wonder whether the decision was at least partially driven by Fed officials’ desire to avoid the perception of yielding to political pressure. In either case, therefore, the public might come to believe the Fed is responding to political factors rather than economic data. Hence, the integrity of monetary policy suffers either way.

Credibility is hard earned and easily lost. That credibility is especially important in the international context. As the issuer of the world’s primary reserve currency, the US dollar’s value depends not only on the economic fundamentals in the United States, but also on the belief that the Fed will conduct policy in accordance with the economic fundamentals. Political meddling undermines that belief. A politicized central bank is one that foreign investors and trading partners may learn to doubt. Additionally, it can have a negative impact on the US Treasury’s international market.

With signs of disagreement emerging within the Fed’s Board of Governors on whether to pivot toward rate cuts later this year, the institution finds itself in a difficult position. Even if the eventual decision is economically justified, it risks being interpreted through a political lens. It is also likely that the Trump administration will publicly claim a victory over the Fed when cuts eventually begin, encouraging the political interpretation. In sum, the damage is already done: not necessarily to inflation or employment, but to the foundational principle of sound money itself.

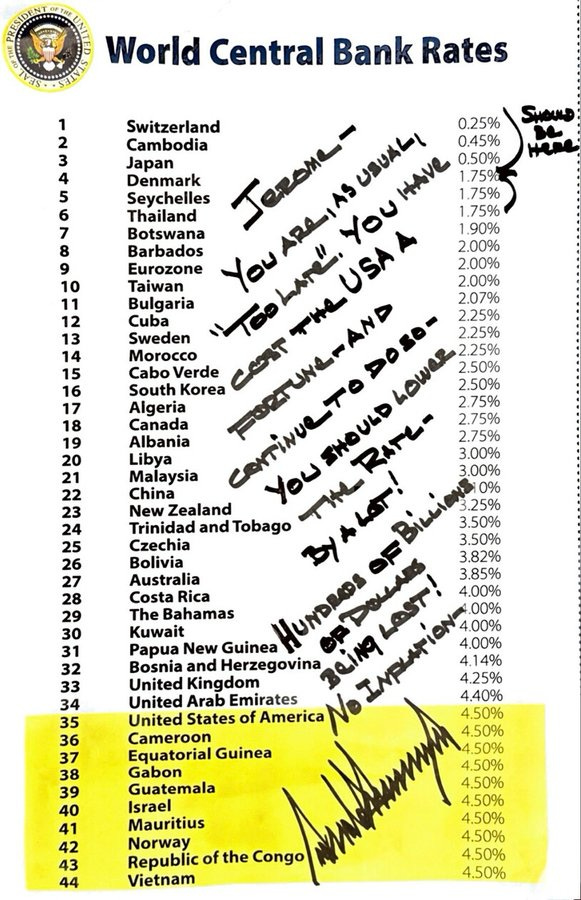

Lower Rates Abroad, So Why Not Here?

Amid growing calls for the Federal Reserve to begin lowering interest rates, White House officials (and the president himself) have adopted the tactic of pointing to the nominal policy rates of foreign central banks as evidence that the Fed is behind the curve.

At best, it’s a misleading argument; at worst, it’s intellectually lazy. Comparing nominal interest rates across countries without accounting for key differences ignores basic monetary economics. Such claims may be politically expedient, but they risk distorting public understanding of the Fed’s mandate and undermining its independence at a time of heightened macroeconomic complexity. They also invoke the memory of recent attempts to influence opinion by misciting, or oversimplifying, economic fundamentals.

Policy rates are set in the context of domestic inflation dynamics, output gaps, and labor market conditions. The US currently faces core inflation above target, low unemployment, and elevated nominal wage growth—conditions not mirrored in Japan (which is emerging from decades of deflation), Switzerland (which has had persistently low inflation), or Costa Rica and Trinidad (which may be responding to different structural or commodity-related factors). Monetary policy must reflect local macroeconomic fundamentals, not foreign benchmarks.

Monetary policy cannot be compared across countries without accounting for structural differences in regime and context. Japan’s yield curve control and Switzerland’s experience with negative interest rates stem from persistent disinflationary forces and efforts to manage currency strength, not from recent inflation dynamics. Additionally, the credibility of central banks and the degree to which inflation expectations are anchored vary significantly across jurisdictions. As the steward of the world’s dominant reserve currency, the Federal Reserve faces a distinct obligation to maintain policy clarity and price stability in order to uphold both its institutional credibility and the international standing of the dollar.

Interest rates are also shaped by long-run structural factors: demographic trends, productivity growth, and capital formation. Japan, for example, has an aging population and weak demand for credit, which structurally suppresses neutral interest rates. In contrast, the US has stronger demographic momentum and capital-intensive sectors that support higher natural real rates. Using lower interest rates abroad to argue for US rate cuts ignores divergent long-run neutral rates (“r^*,” “r-star”) across economies.

Many countries with lower interest rates have different exchange rate regimes or weaker currencies and rely more on capital inflows or export competitiveness. For instance, Trinidad and Costa Rica have narrower monetary transmission mechanisms and more fragile current accounts. The US runs persistent deficits and issues the global reserve currency, meaning its rates carry a different weight in global capital flows and must be managed to preserve external stability and dollar demand. Lowering US rates based on foreign benchmarks could destabilize capital flows or re-ignite inflationary pressures.

Cross-country comparisons of policy interest rates may offer superficial appeal, but they are ultimately inadequate—and often misleading—when used to evaluate the stance of Federal Reserve policy. Simply pointing to lower nominal rates in countries like Trinidad and Tobago, Cambodia, or the United Arab Emirates overlooks the profound differences in underlying economic conditions, institutional mandates, and monetary frameworks. Inflation dynamics vary widely, as do levels of debt, productivity growth, and labor market slack. Central banks also differ widely in the degree of independence they enjoy, the tools they deploy, and the inflation expectations they must manage.

This is not a defense of the Federal Reserve, or Fed Chair Jerome Powell, or of central banking as an economic institution. It is a defense of sound economics—of the importance of applying consistent analytical frameworks, respecting empirical nuance, and resisting the temptation to cherry-pick statistics for political expediency. It would be as sensible to compare the shoe sizes of runners to determine who is fastest.

Analyzing monetary policy requires more than headline comparisons and talking points; it demands an understanding of real versus nominal variables, institutional context, and the global role of the US dollar. Stripping away that rigor weakens public discourse, distorts expectations, and ultimately undermines the very outcomes—price stability, sustainable growth, and economic resilience—that sound policies aim to achieve.

QTR’s Disclaimer: Please read my full legal disclaimer on my About page here. This post represents my opinions only. In addition, please understand I am an idiot and often get things wrong and lose money. I may own or transact in any names mentioned in this piece at any time without warning. Contributor posts and aggregated posts have been hand selected by me, have not been fact checked and are the opinions of their authors. They are either submitted to QTR by their author, reprinted under a Creative Commons license with my best effort to uphold what the license asks, or with the permission of the author.

This is not a recommendation to buy or sell any stocks or securities, just my opinions. I often lose money on positions I trade/invest in. I may add any name mentioned in this article and sell any name mentioned in this piece at any time, without further warning. None of this is a solicitation to buy or sell securities. I may or may not own names I write about and are watching. Sometimes I’m bullish without owning things, sometimes I’m bearish and do own things. Just assume my positions could be exactly the opposite of what you think they are just in case. If I’m long I could quickly be short and vice versa. I won’t update my positions. All positions can change immediately as soon as I publish this, with or without notice and at any point I can be long, short or neutral on any position. You are on your own. Do not make decisions based on my blog. I exist on the fringe. The publisher does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information provided in this page. These are not the opinions of any of my employers, partners, or associates. I did my best to be honest about my disclosures but can’t guarantee I am right; I write these posts after a couple beers sometimes. I edit after my posts are published because I’m impatient and lazy, so if you see a typo, check back in a half hour. Also, I just straight up get shit wrong a lot. I mention it twice because it’s that important.

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: Quoth the Raven

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://quoththeraven.substack.com feed and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.