This is the second entry in a new series: Part 1 focused on Alexander Hamilton.

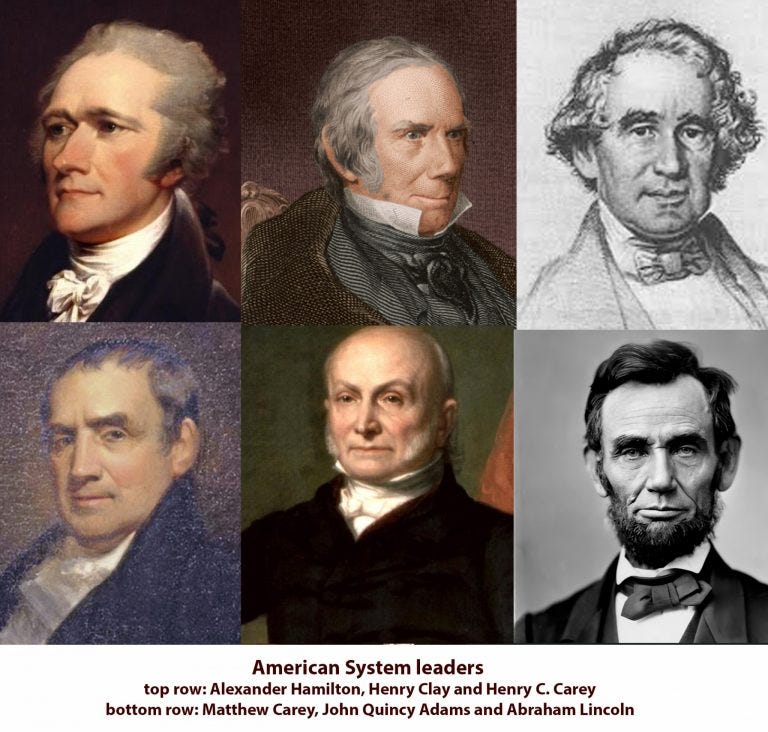

In my last paper I introduced the figure of Alexander Hamilton (first Treasury Secretary and founder of the American System of political economy).

In that location, I contrasted Hamilton’s system which tied the value and behaviour of money to the increasing powers of production of a society through manufacturing and internal improvements, to the opposing system of British free trade which tied value to hedonistic impulses and the worshiping of money.

In this sequel, I’d like to take a moment to explore another figure of American history who has become the cause of serious arguments among patriots … Abraham Lincoln.

Some citizens love him as an angelic savior of America and others hate him as a wicked tyrant, even going so far to celebrate his 1865 murder to this very day… yet, upon scratching behind the surface of both popular narratives, I contend that both extremes of this narrative war have been duped.

To make matters worse, the state of economic affairs was impossibly unmanageable, with over 7,000 recognized bank notes in the USA, and over 1,496 banks each issuing multiple notes. Under this highly de-regulated system made possible by the 1836 killing of the national bank years earlier under Andrew Jackson and the passage of the 1846 Independent Treasury Act, which prevented the government from influencing economic affairs, every private bank could issue currencies with no federal authority.

With such a breakdown of finances, no national projects were possible, international investments were scarce, and free market money worshipping ran rampant. Manufacturing collapsed, speculation took over and the slavocracy grew in influence between the 1837’s bank panic and 1860.

In his pioneering book Who We Are: America’s Fight For Universal Progress volume 2, Anton Chaitkin writes of the artificial crisis of 1837-1860:

“Under anti-national economic regimes since the 1830s, there had been no national currency and no federal regulations on banks.

State-chartered banks used deposits for dangerous speculation. To make loans, they issued paper notes in various dollar amounts, promising to pay off in gold or silver coins (“specie”) if a note were cashed in (a promise that could be kept only if the bank did not overextend itself). These notes circulated as a kind of money, but they were often not accepted for payment far from the locality of the issuing banks.

In the crisis of the Union, fear for the future had shriveled credit and investment. Southerners had stopped paying most debts they owed to northern business. The bigger northern banks were trying to hoard gold. In these chaotic circumstances, depositors and note-holders across the country were often left with nothing.”

By the onset of the Civil War, the City of London was obviously not interested in allowing the USA to get out from under water, and with the gold-backed pound sterling, ensured the manipulation of gold prices and orchestrated the buyout of U.S. gold reserves. When Lincoln sought loans to execute the war, whether from Wall Street or International banking houses, the loans were granted only at excessive interest rates of 20-25%.

[…]

Although 150 years of revisionist historians have obscured the real Lincoln and the true nature of the Civil War as a British-run operation to undo the revolution of 1776. The martyred president was always an opponent to slavery, and always situated himself in the traditions of the American System of Hamilton, describing in 1832 a policy which he later enacted 30 years later:

“My politics are short and sweet, like the old woman’s dance. I am in favor of a national bank. I am in favor of the internal improvement system, and a high protective tariff. These are my sentiments and political principles.”

In 1859, Lincoln described himself

“I was an old Henry Clay tariff whig. In old times I made more speeches on that subject, than on any other. I have not since changed my views.”

Lincoln’s commitment to the Hamiltonian system of national banking was showcased brilliantly during his 1840 campaign speeches promoting Harrison’s Whig presidency and the restoration of the bank, which had been cancelled by Andrew Jackson four years earlier.

[…]

From this period in the Congress where he became a leading ally of John Quincy Adams, and played a leading role in opposition to the unjust U.S.-Mexican War, Lincoln committed himself consistently to ending not only systems of slavery, but also all hereditary power structures internationally, which he understood were inextricably connected.

[…]

Lincoln Revives the American System

The Bank Act of 1863 established reserve requirements for the first time, and also capped the interest rates in order to destroy usury within the nation itself. In order to eliminate international interference and manipulation from Wall Street financiers, the Bank Act also forced 75% of all bank directors to reside in the state in which the bank was located, and all directors had to be American citizens.

The most important step in this fight was the sovereign control of credit issuance, which, according to Article 1 section 8 of the U.S. constitution can only be affected through the U.S. treasury (an important lesson for anyone serious about ending the privately run Federal Reserve controls over national finance today). Following this constitutional principle, Lincoln issued a new form of currency called Greenbacks, which could only be issued against U.S. government bonds. These began being issued with the 1862 Legal Tender Act.

Nationally-chartered banks were now obliged to deposit into the federal treasury, totalling at least one third of their capital in exchange for government notes issued by the Mint and Treasury (in order to qualify for federal charters needed to avoid the tax on state bank activities, banks found themselves lending to the government, which gave Lincoln an ability to avoid the usurious loans from London and Wall Street.)

New bonds were issued under this scheme called 5:20 bonds (due to their 5-20 year maturation), which citizens purchased as investments into their nations’ survival. These bonds, which united “personal self interest” with the general welfare of the nation provided loans to manufacturing, and as well served as the basis for the issuance of more Greenbacks.

Organized by Lincoln’s ally Jay Cooke (a patriotic Philadelphia banker), the 5-20 bonds were sold in small denominations to average citizens who then had a vested interest in directly participating in saving their nation.

Between 1862-1865, these bonds accounted for $1.3 billion.

[…]

These measures were accompanied by a strong protective tariff to grow American industries as well.

By the beginning of 1865, $450 million in Greenbacks were issued, making up over half of all currency in circulation.

[…]

Via https://matthewehret.substack.com/p/in-defense-of-abraham-lincoln-and-077

Click this link for the original source of this article.

Author: stuartbramhall

This content is courtesy of, and owned and copyrighted by, https://stuartbramhall.wordpress.com and its author. This content is made available by use of the public RSS feed offered by the host site and is used for educational purposes only. If you are the author or represent the host site and would like this content removed now and in the future, please contact USSANews.com using the email address in the Contact page found in the website menu.